National

Long wait for loved ones—and for justice

On a chilly evening on January 3, 2004, about a dozen police officers in civilian clothing came to the Bhotahiti-based shop of Hira Bahadur Roka and asked him to come along for questioning. They didn’t tell him what it was about or where he was being taken, but they assured him that he’d be released within a few hours.Fourteen years later, Roka’s family is still waiting for him to return. Following months of search, the family discovered that Roka had been taken to Maharajgunj-based Bhairavnath Battalion of Nepal Army, after he was held inside a few police stations within the Valley.

Binod Ghimire

On a chilly evening on January 3, 2004, about a dozen police officers in civilian clothing came to the Bhotahiti-based shop of Hira Bahadur Roka and asked him to come along for questioning. They didn’t tell him what it was about or where he was being taken, but they assured him that he’d be released within a few hours.

Fourteen years later, Roka’s family is still waiting for him to return. Following months of search, the family discovered that Roka had been taken to Maharajgunj-based Bhairavnath Battalion of Nepal Army, after he was held inside a few police stations within the Valley.

Roka, 35, had moved from a small village in Nuwakot to Kathmandu, where he’d been running a cloth shop. “Security officials suspected he was supporting the Maoists, but that was not true,” Roka’s wife, Bishnu, told the Post. “We had no links to Maoists.”

When Nepal declared a state of emergency following deadly clashes between the Maoists and the Army in 2001, security forces routinely picked up individuals they suspected had ties to the Maoist rebels. Across the country, people were being detained by both the Army and the Maoists—and then disappeared.

According to the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons, by the end of the decade-long insurgency, there were 3,196 complaints of disappearances by the state and the Maoists, of which at least 2,369 have been identified as ‘genuine’ cases. A report by the International Committee of the Red Cross, which has been keeping a record of the disappeared from the beginning of the Maoist war in 1996, shows that 1,333 people are still missing.

About 75km east from Kathmandu, in the Dapcha village of Sindhupalchok district, the Lama family shares a similar story—except that the individuals responsible for their agony were rebels from the People’s Liberation Army.

Arjun Bahadur Lama, 45, was attending a ceremony at a local school on April 29, 2005, when a group of Maoist combatants grabbed him, saying they wanted to talk about some issues. The Maoists and their People’s Liberation Army, which had full control over the district, never released Lama.

Hundreds of families whose kins were forcibly disappeared during the Maoist insurgency have similar painful stories. Though the peace-process has been largely completed and the country has adopted an entirely new governance system after the promulgation of the new constitution, the fate of thousands of victims of the insurgency still hangs in a limbo.

For the last 13 years, Lama’s family has knocked on the doors of every government offices and non-government organizations, but to no avail.

“We are suffering all these years just because my husband denied supporting the Maoists,” his wife, Punya Maya, told the Post.

Both the Roka and Lama families have filed cases with the police, the National Human Rights Commission, and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons, pinpointing the names of the accused. But officials have not moved the case even by an inch.

“Every evening, I still feel like Arjun would come home and knock on the door,” Punya Maya said. “I can’t bear the pain anymore. I would rather accept his death than live in this uncertainty. The government must produce him before me, alive or dead.”

On November 21, 2006, when the Maoist revolutionaries joined mainstream politics following a Comprehensive Peace Accord with the government, forming transitional justice mechanisms, providing justice to the victims and revealing the status of the disappeared people was a crucial agenda.

One of the major clauses in the agreement stipulates that both sides—the government and the Maoists—agree to make public, within 60 days of signing the comprehensive accords, information about the real name, caste, and address of the people disappeared or killed during the war, and inform the family members about it.

However, it took over eight years for the government to just form the commission, CIEDP, to investigate the status of the disappeared. What’s worse, the commission has largely failed to dig into the cases three and a half years after its formation.

Bishnu says the government’s decision to promote then chief of Bhairavnath Battalion, Raju Basnet, who is one of the key officials accused in disappearing her husband—Basnet has also been accused of disappearing 48 others during the course of the insurgency—shows that the Maoists and the government are deliberately stalling the investigation and denying justice to the victims.

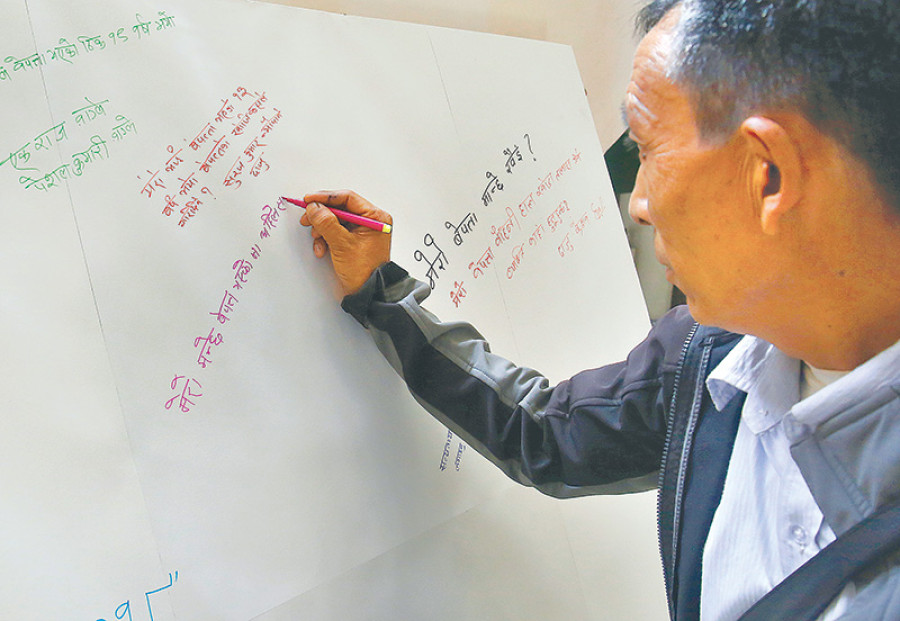

Civil society groups have accused the government of trying to tire out the victims so they get frustrated and give up. “But we won’t give up unless we know about the status of our relatives and those involved in the heinous crime are punished,” said Ram Kumar Bhandari, the president of Nepal Society of Families of the Disappeared and Missing, during an event on the International Day of Disappeared in the Capital on Wednesday.

Bhandari said that the CIEDP hasn’t even cared to investigate into the disappeared cases in Bhairavnath, Chisapani, Charaali, Bhorletar, and Dhanusha Battalions—which have been accused of forcibly disappearing dozens of people. None of the battalion commanders has been interrogated, let alone asked to release a statement, on the accusations by hundreds of victims’ families.

“Justice delayed is justice denied,” Bhandari added. “The commission should either deliver or give up.”

Officials at the commission say they can understand the pain and frustration among the families and are working to resolve the cases despite different constraints. Lokendra Mallick, the chairperson of CIEDP, told the Post that the commission has completed a preliminary investigation of 1,210 cases from 43 different districts.

Mallick said the commission hasn’t been able to recommend the actions against the perpetrators because there are no legal provisions to criminalise the forceful disappearance. The criminal code that came into effect on August 17 has criminalised forceful disappearance, but it does not apply to crimes committed before the law went into effect, essentially ignoring all the war-era disappearances.

“I urge the victims to put pressure on the government as well, so it can introduce such a law,” Mallick said, reiterating that the commission is committed to providing justice to the victims.

But families of the disappeared individuals say they have no hope from the commission.

“I think the formation of the commission is simply a ploy to linger the process and never reveal the truth,” said Bishnu, Roka’s wife. “If it isn’t, then why hasn’t it recommended any actions against those involved in forceful disappearance while there are abundant proofs against them?”

22.85°C Kathmandu

22.85°C Kathmandu