Movies

The artistry of mortality in ‘Drawing Closer’

The movie explores how dying young doesn’t mean living less, but living deeper, with quiet defiance.

Skanda Swar

Takahiro Miki’s ‘Drawing Closer’ addresses a timeless and complex cinematic theme: young love trying to thrive in the face of life and death at every turn.

However, rather than surrendering to the sentimentality found in romance and illness genres, Miki creates a meditation on mortality as optional understandings of life arise when existence is visible, confined, and empirically measured.

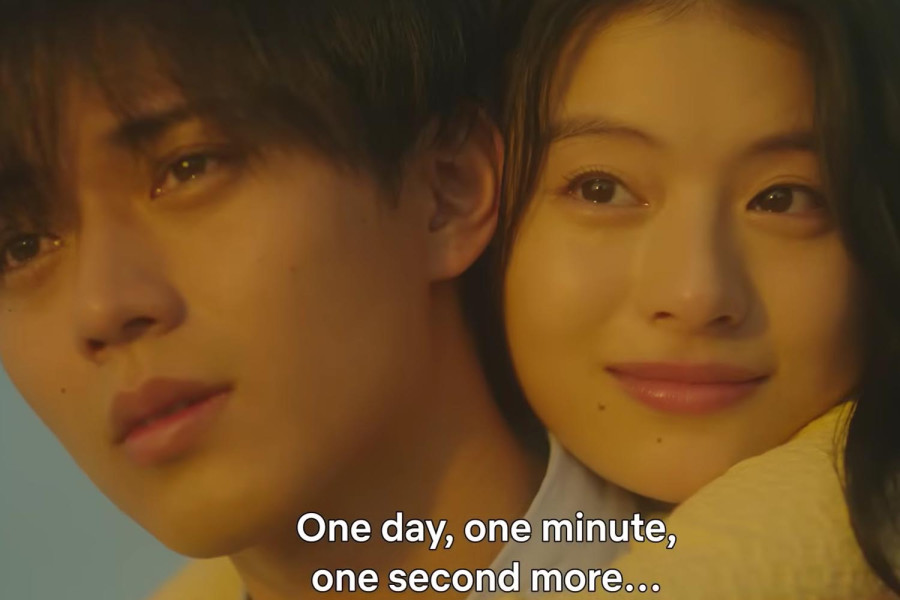

Accompanied by the vulnerable performance of Ren Nagase and Natsuki Deguchi, we follow seventeen-year-old Hayasaka Akito (Nagase), an artist, who has a heart tumour and is expected to live for a year.

However, when he meets Haruna, he discovers she has even less time—only six months. What starts as an awkward inclination toward one another becomes more than a coincidence—it becomes something essential and life-changing.

Miki’s brilliance is evident in her refusal to use terminal illness as a trigger for love or tears. Instead, the circumstances they face complicate their redemption, almost suggesting that death renders life even more valuable.

For instance, Akito’s passion for art sustains him; death does not complicate the living experience because it imposes too much pressure on him. Akito must preserve his innocence in his new reality, understanding that he will no longer be on Earth. So, why not create art while he still can?

Therefore, when the camera focuses on Akito’s drawings for an extended period or highlights how people will miss him in a year, it transforms from merely being memories and creations of an artist into a protest against his life being stolen from him. When Haruna eventually shares her timeline with Akito, it provides them with a solid foundation to recognise the essence of life, confront the harshness of death, and aspire to leave lasting legacies that transcend their physical existence.

Nagase earns praise for his emotional sensitivity and restraint. As a prominent television actor in Japan, he skillfully portrays Akito, avoiding excessive theatrics.

Yet he plays it on par with the insanity of anyone so young, knowing he’s going to die decades earlier than expected. He approaches it with a graceful pride, fully aware of what lies ahead. His artistry isn’t a product of pressure; instead, his innate sensitivity defines him as an artist. Consequently, Miki allows Nagase to express what words cannot convey when they fall short of articulating the inexpressible.

Deguchi’s portrayal of Haruna represents not just an obstacle to Akito’s journey or a romantic interest but also a complementary route to acceptance. While Akito employs his brush to express his thoughts and emotions, Haruna exemplifies someone who must capitalise on her limited time by embracing life through direct experiences and as much engagement as possible.

Therefore, their chemistry develops organically, unencumbered by pressure, contrasting with the intimacy often associated with romantic pursuits affected by terminal illness. They do not find each other attractive due to circumstance; instead, they recognise each other’s flawed but significant diagnoses that do not need repressed expressions or diminishment outcomes. They appear to each other as if captured in static frames of Akito’s artwork, arising from both creative and physical decline, yet boldly defying the norm by continuing to relish in each other’s company.

Miki’s directorial vision conveys this naturally oriented meaning through nuanced cinematography, which prevents the film from becoming melodramatic through spectacle. The camera is always close to the characters (documentary style almost), connected to an honest sense of time and space, instead of overly dramatised experiences filled with excessive outreach.

The editing and pacing during the first two acts speak to this reality; unlike many romantic tributes where quick cuts and speeding up increase the inevitable romance faster than one can comprehend, here, scenes and moments get the chance to breathe as characters acknowledge the sentimentality of it all. This temporal approach becomes part of the film’s broader examination of how awareness of mortality changes one’s relationship with time itself.

The film rises above what might have been a superficial premise by emphasising the qualitative aspects of their remaining time rather than the quantitative ones. It delves into how meaning is derived not from the length of time but from the depth of experience and the strength of connections. This philosophical underpinning enhances the narrative, steering it away from conventional tearjerkers and allowing for sincere reflection on mortality, love, and the human ability to discover beauty within tragedy.

The film’s exploration of family dynamics and social relationships adds complexity, preventing it from becoming an isolated love story. While not extensively developed, the supporting characters provide context for understanding how terminal illness affects not just the diagnosed but their entire social networks. These relationships illuminate the broader themes about legacy, memory, and how individuals impact the lives of others, even when their own time is limited.

‘Drawing Closer’ succeeds because it treats its characters as complete human beings rather than symbols or vehicles for predetermined emotional responses. The film earns its emotional moments through character development and genuine situations rather than manipulative techniques or artificial sentiment. While the premise may feel familiar to audiences versed in terminal illness romance narratives, Miki’s execution demonstrates that familiar territory can still yield fresh insights when approached with intelligence, sensitivity, and respect for the complexity of human experience.

Ultimately, ‘Drawing Closer’ is a thoughtful exploration of how individuals create meaning in the face of mortality, offering viewers not easy comfort but genuine contemplation about the nature of love, time, and the human capacity for finding beauty even in life’s most challenging circumstances.

The film suggests that while we cannot control the duration of our existence, we retain agency over its depth and significance, making each moment a choice about how to live rather than simply how to survive.

_____

Drawing Closer

Director: Takahiro Miki

Running time: 2 hours

Language: Japanese

Year: 2024

Available on: Netflix

13.54°C Kathmandu

13.54°C Kathmandu