Movies

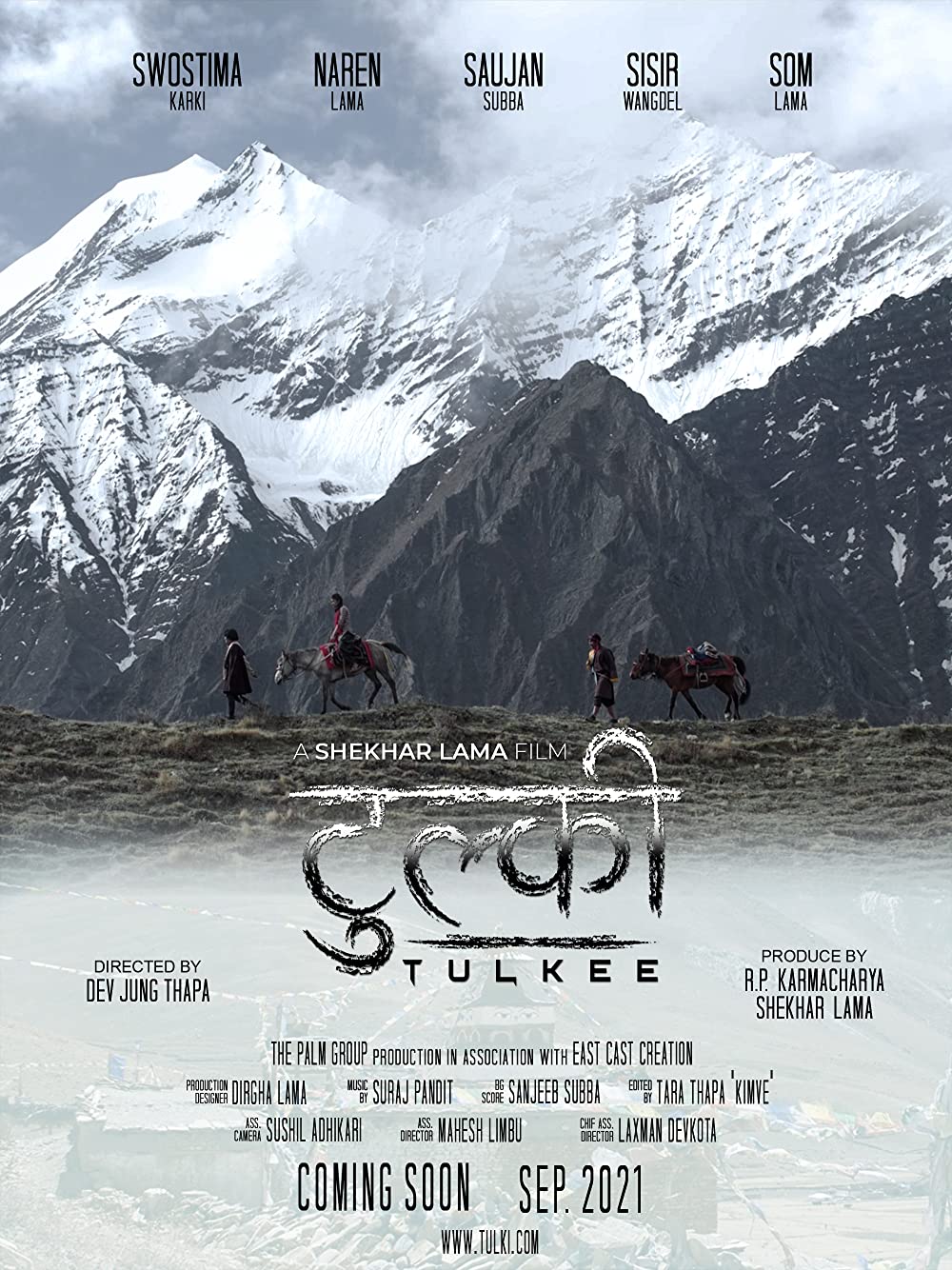

‘Tulkee’: A woman’s pain is not a plot device

Sorry folks, putting a female character through the worst possible circumstances to say, ‘Oh no! Bad things happen to women,’ isn’t good storytelling.

Urza Acharya

Some movies are bad. You know, dense dialogues, flaky plot, bad acting. But they’re fun to deconstruct or hate-watch. Think ‘The Room’ or ‘Mrs Serial Killer.’ But some movies are dangerous. They’re so cruel, detached, and painful to watch that you’re left with a sense of dread—over what happens in the story, but mostly over how this particular film even made it to the screens—with so many people on board.

‘Tulkee’ was the latter. Even as I write this review, I’ve blocked a part of my mind from feeling things, afraid I’ll internalise what I saw on screen. The story follows the life of Tulkee—a Bramhin girl born and brought up in a village near Shey Phoksundo Lake in Dolpa.

And boy, does she have a hard life. No, hard won’t cut it. The writer wanted to make sure that she should suffer, suffer and suffer some more. Let me tell you the story (spoiler alert, I guess): Tulkee’s mother dies when she is young, and her father brings home the ‘evil’ stepmother. Sangey (the supposed hero) grabs her and forcefully takes her home, and now, because of the ‘polyandry’ tradition (per the cultural norm in Sangey’s family), she is also married to two of his older brothers who, you guessed it, assault her on marital grounds.

As if this wasn’t enough, she is assaulted once more by a neighbour and then blamed for having an affair. One of the brothers kills Sangey, the only husband that actually cared for her, and then (while pregnant and literally chained up) she kills her perpetrators and herself by drinking poison (which was so conveniently available at that very moment).

This plot isn’t just bad. It’s dangerous. In the guise of telling a ‘social story’, the movie is just a facade to see a woman in pain—as evident by the lingering camera angles after Tulkee is raped. ‘Fridging’ is a term used for a trope in films where a woman is either killed, raped or brutalised just to move a male character’s story arc forward. The term comes from an episode of the Green Lantern comic where the superhero finds his girlfriend chopped up and put in the fridge and only then finds the energy to fight the villain.

The same thing happens in ‘Tulkee’. Although Tulkee goes through the worst horrors possible, it’s Sangey who gets multiple scenes where he walks up to the hills and yells loudly because he’s so much in pain having to ‘share’ his wife. In fact, when he comes home after that, it is Tulkee who comforts him.

The film is misinformed in so many aspects. The ‘love story’ comes out of nowhere. During her menstruation-banished walk, Tulkee briefly sees Sangey, and voilà, a smile from both implies that they are head-over-heels.

Yes, I get it Nepali films want to show societal truth. This film’s narrative seems to shed light on the polyandry tradition prevalent among some communities in the Himalayan Region. And, of course, the ways in which the women suffer because of it. To people who say, “This was what it was like back then,” if it really was this bad, I’m sure no women would be left in the villages. I mean, there’s only so much someone can take.

I think we owe it to our ancestors, both men and women, to have some form of rationality and morality. The film shows the characters—especially the men—to be so barbaric it’s next to impossible to understand their actions by saying, “It was the sign of the times.” And the women are so passive—either too pure and innocent or too conniving—that it’s clear that they are manufactured by the male gaze, in this case, of the writer and the director.

It gets tiring at times. Things have become so normalised that women let smaller transgressions pass because they don’t want to seem “difficult.” But then you see a movie that is so cruel—in the name of showing women’s plight—that it leaves you empty and terrified. That is what I felt.

Clearly, a lot of time and money went into making this film. The director, writer, actors and producers must have had some rationale for making the film, which has clearly evaded me. But in the end, their rationale doesn’t matter. Because the minute you put it out for others to see (the author is dead, they say), the story is carried on by audiences’ perceptions and judgement. And the message ‘Tulkee’ puts out is a distressing one.

While watching the film, I recalled an incident in a film studies class; a film director (a woman) said, “Dear men! Please stop making movies about us.” Somedays, I can’t help but agree.

Tulkee

Language: Nepali

Duration: 2 hours 14 minutes

Director: Dev Thapa

Cast: Sishir Bangdel, Som Lama, Swostima Karki, Himali Hamal, Shekhar Lama

Released: May 26

Now showing: One cinemas, QFX cinemas

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu