Movies

A mediocre story but an excellent film

Director Dinesh Raut’s treatment of the source script is what sets ‘Prakash’ apart from other films exploring similar themes.

Abhimanyu Dixit

The review contains spoilers of the film.

As you settle down to watch the new Nepali film ‘Prakash’, theatres will exhibit trailers of two upcoming films—‘Samhalincha Kahile Mann’ and ‘Jhinge Dau’. The former is a glossy urban love story that uses tropes from Bollywood and Korean dramas to present melodramatic sequences, bright images, and some dull-witted philosophy on what love is. It stars Pooja Sharma, an actor whose entire filmography centres around playing the same role of an urban girl looking for love.

Whereas ‘Jhinge Dau’ is a rural social drama that presents village life as backward and gaudy. Like countless films set in rural Nepal, you will find radio drama-esque sequences where everything must be spelt to the audience in a loud and cringy overtone.

These two themes have been Nepali cinema industry staples for the past two to three decades and are a product of filmmakers who conveniently remake the same genre, style, and issues. The reason is that Nepali filmmakers are either afraid of experimentation or think the audience is docile and will not demand anything more.

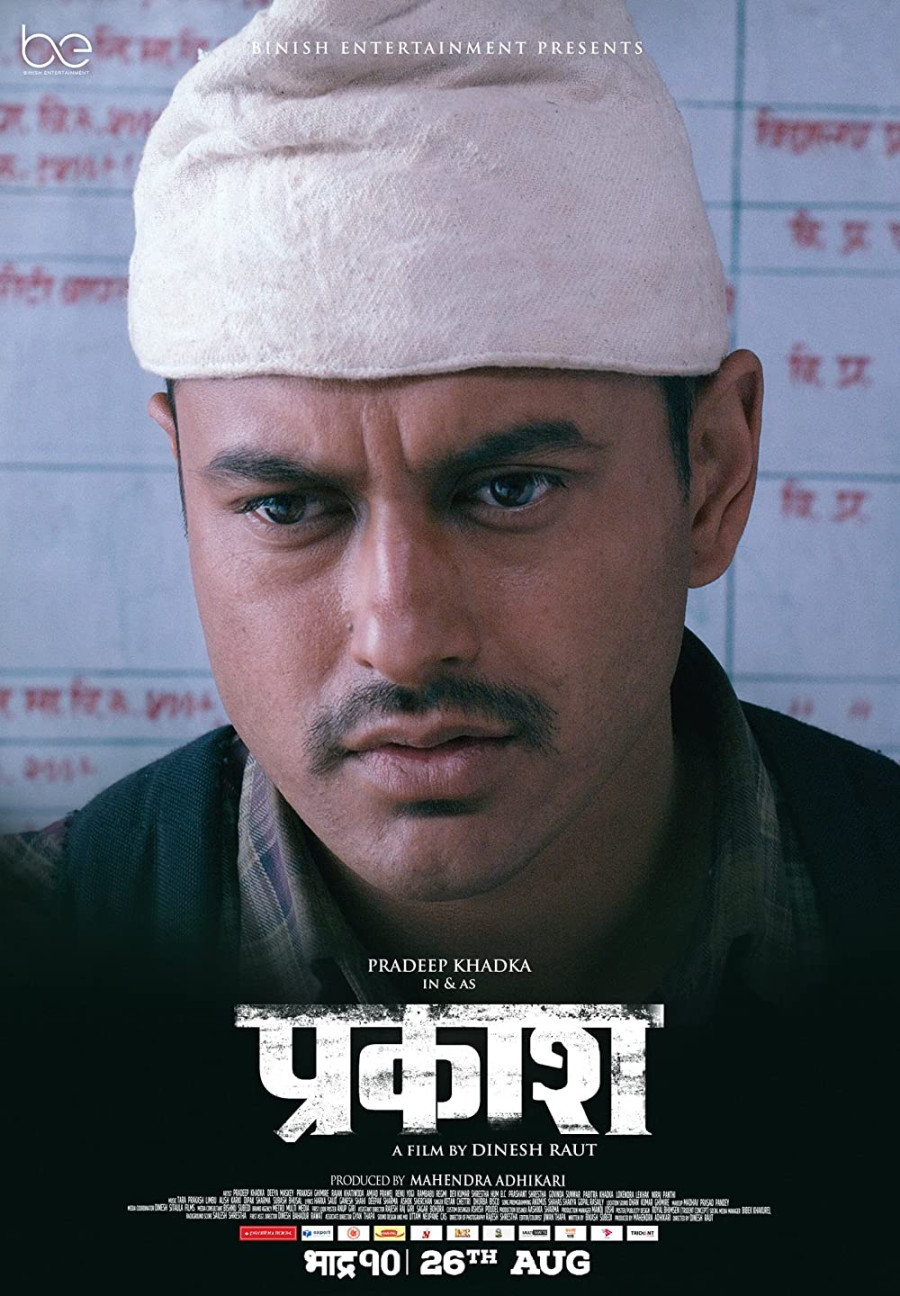

Compared to the two films, ‘Prakash’ seems like it is from another dimension. Like ‘Samhalincha Kahile Mann’, the film has a superstar, Pradeep Khadka, and, like ‘Jhinge Dau’, the film is set in rural Nepal, but the presentation, tone, and execution make ‘Prakash’ stand kilometres apart.

Set in western Nepal, we first meet the titular character Prakash (Pradeep Khadka) when he runs through a funeral procession to deliver good news to his mother, Sita (Deeya Maskey). His mother, despite poor health, works in a barren field with a halo (plough). Prakash also has a love interest, Radha (Renu Yogi), but more about her later.

The film is written by Bikash Subedi. On paper, the film’s plot sounds like a Hindi film (from the 1960s) set in a rural village. Prakash is an optimist. He wants to pass his exam and work as a teacher in a government school. However, the system is believed to be corrupt and rigged against the poor, and Prakash might not fulfil his dreams.

The film’s antagonists are stereotypical. They are rich and powerful landlords Indraprasad (Prakash Ghimire) and Jwairaja (Rajan Khatiwada)—they are reminiscent of Lala (Kanhaiya Lal) of ‘Mother India’ (1957) and revel in wrongly stealing money and torturing the poor.

Prakash, the character, is also quite passive. Things happen to him, and he only reacts to them. We rarely see Prakash initiate anything. Remember Prakash’s love interest Radha? Well, it turns out Radha is from a lower caste. When Radha tells Prakash they cannot be together, Prakash listens, gestures about fighting the system together, and then do nothing to further that subplot.

Subedi, the writer, is hellbent on making Prakash’s life miserable. The story dictates the character and not the other way around. Bit by bit, the writing chips away at Prakash, taking away everything he holds dear. The film’s central idea revolves around what happens when you push the common man to their breaking point.

Subedi also writes redundant scenes. For example, every time you see Indraprasad and Prakash together, the scene is about how much Indraprasad hates Prakash. You will also find redundancy in scenes with Prakash and his mother. Every scene with the two is about poverty.

Redundant scenes and the story dictating the characters risk the audience disconnecting. A passive lead through the majority runtime would have turned this into a boring film. But the film is saved because of Khadka’s performance as the lead character.

Khadka’s filmography is also like the aforementioned Pooja Sharma. He also plays a lover in most of his films. But in ‘Prakash’, Khadka risks his ‘lover boy’ persona to attempt something very different and does it excellently.

First, Khadka nails the accent and his delivery. But, to achieve this transformation, Khadka doesn’t change his voice or apply heavy makeup. He transforms by acting as someone full of hope—and you as an audience are convinced with this performance. For example, in one scene, Prakash tells his mother that he wants to be respected. He doesn’t want people to derogate him by calling him ‘Prakashe’, but he wants people to say ‘Namaskar, Prakash Sir’, and Khadka is convincing and makes us root for him. Instances of such performance turn the passive character empathetic.

Another actor who matches Khadka’s performance is Renu Yogi as Radha. Scenes with Yogi and Khadka just fill you with joy. Their chemistry works so much that everyone else in the film, even the veteran Deeya Maskey’s performance, looks bland in comparison. For example, in one scene, Prakash storms off angrily and his mother runs after him. But she loses her footing and falls down, and stops chasing. Some background music conveys her emotion, but we are indifferent to this. Almost immediately, Prakash spots Radha, and he goes after her. In this instance, we are filled with excitement and anticipation. Both scenes with Maskey and Yogi are similar, but courtesy of better performance, we are more invested in the latter’s story.

On paper, ‘Prakash’ reads like a stereotypical Nepali film presenting social commentary on ‘rural life under a corrupt political system’. We’ve seen this narrative unfold with comic overtones in ‘Cha Maya Chhapakkai’ (2019) or as a drama in ‘Talakjung VS Tulke’ (2014). But what sets ‘Prakash’ apart from these is director Dinesh Raut’s treatment of the source script. The film could have turned into a cliche 1960s Hindi film, but Raut’s direction did not let the film wander around.

Before ‘Prakash’, Raut’s filmography consisted of glossy love stories like ‘November Rain’ (2014). But lately, he has switched genres and applied himself to more grounded projects like ‘Prasad’ (2018) as a director and ‘Selfie King’ (2020) as a producer.

For ‘Prakash’, Raut uses wider frames and longer takes, allowing us to constantly connect the environment with the character. The emotions portrayed also remain unbroken. The scenes of Radha and Prakash work because they are shot in unbroken longer takes, with both of them together in the scene, making us feel the connection. Raut’s collaboration with his cinematographer, Rajesh Shrestha, should also be commended here. In the outdoor scenes, you always see the expanse of the terrain with the sun acting as the only light source. In the indoor scenes, Shrestha follows the source of light, usually a tuki (lantern), making the image look more realistic.

Also, Raut’s use of a bridge as a motif is also excellent. The first image of the film is a wooden statue on the bridge. We also learn that it was on the same bridge where Prakash had seen his father for the last time. Prakash also sees Radha on the bridge for the last time. A bridge that connects two land masses here is a very ominous sign of separation.

Going by the film’s strong word-of-mouth publicity and recent occupancies in cinema halls, ‘Prakash’ seems well on its way to becoming a hit. This is absolutely encouraging for Nepali cinema which aims to experiment and go against market norms.

Films like ‘Prakash’ are very important for Nepal’s cinema, not just to encourage experimentation but also to motivate mainstream actors to work in non-mainstream films. We want to see more of this side of Nepal’s cinema. We would love to see actors of ‘Samhalincha Kahile Mann’ and ‘Jhinge Dau’, the staple of Nepali cinema, collaborating with the makers of films like 'Prakash'. I hope they can see the light and take Nepali cinema forward.

20.72°C Kathmandu

20.72°C Kathmandu