Money

Why has Nepal failed to attract enough foreign direct investment?

Foreign direct investment is vital for accessing new technologies, business practices, and markets, especially when the country aims for the middle-income tag.

Prithvi Man Shrestha

Nepal aims to become a middle-income country and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. But the current level of investment is not enough for the country to reach the middle-income stage from the current low-income status as targeted, according to a World Bank report.

Nepal’s investment to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio for 2001-2016 stood at 21 percent, which needs to increase by more than 10 percentage points to achieve the goal, according to the World Bank Report—Climbing Higher: Towards Middle Income Country—released in May 2017. The National Planning Commission said in a report in June that the country faces a financing gap of Rs 585 billion per year to meet the Sustainable Development Goals.

This resource gap is going to be a major problem for the country in achieving these twin goals. Although the opportunities and financing for investment are present in Nepal, public investment has been low and the country has been unable to crowd in potential private investment, the World Bank assessed in another Nepal report called ‘Systematic Country Diagnostic’.

One of the major sources of bridging the financing gap is foreign direct investment (FDI) but Nepal is one of the countries attracting the lowest amount of FDI in recent years.

Here’s a dissection of the FDI situation in Nepal and the key constraints.

What exactly is the foreign direct investment situation in the country?

The Systematic Country Diagnostic Report published by the World Bank in February last year revealed that FDI has averaged just 0.2 percent of GDP over the last decade, which is one of the lowest in the world. Foreign direct investment is vital for accessing new technologies, business practices, and markets. In the past few years, FDI inflow in the country has seen an upward trend but lags behind most South Asian countries.

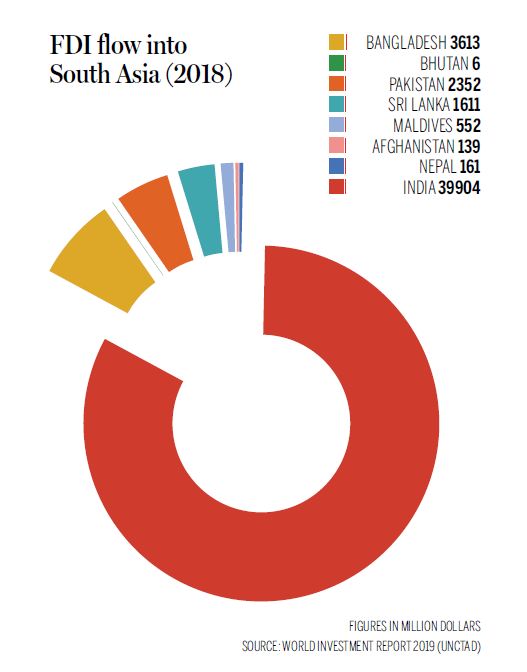

According to an assessment by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Investment (UNCTAD), Nepal was ahead of only the war-torn Afghanistan and tiny Bhutan in attracting FDI in 2017-2018. Nepal received an FDI of $161 million in that year against $139 million by Afghanistan and $6 million by Bhutan.

Countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are far ahead of Nepal in attracting FDI in South Asia.

According to Nepal Rastra Bank, the FDI inflow decreased in the fiscal year 2018-19 to $115.5 million after an upward trajectory in the previous few years. Realisation of FDI has remained poor although commitments have remained relatively much higher.

For example, FDI commitment to Nepal in fiscal years 2017-18 and 2018-19 stood at Rs55.76 billion ($491 million) and Rs23.94 billion ($211 million), according to the Department of Industry but the country received FDIs of $169 million and $115 million respectively.

How does the political climate deter foreign investors?

Numerous studies carried out in recent years have identified political instability as the biggest constraint to private sector investment and growth in Nepal. But, after the elections in 2017, the country has got a stable government in two decades.

With the country achieving political stability, the government has tried to woo foreign investors by organising events like Nepal Investment Summits in 2017 and 2019. But, FDI flow has continued to remain poor.

Despite political stability, the political climate has not been supportive enough for foreign investors.

One example of how political interest is discouraging foreign investment is the case of Huaxin Narayani Cement, a Nepal-China joint venture company. Two factions of the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) quarrelled over leasing land to the factory by Benighat Rorang Rural Municipality, Dhading, for 50 years.

The issue reached the Parliamentary Public Accounts Committee, which directed the government against the land handover and the deal was cancelled. This prompted a strong reaction from Suraj Vaidya, a joint venture partner from Nepal. “The parliamentary committee didn’t provide us with an opportunity to clear things up. Under such circumstances, how can I guarantee that foreign investors will stay here?” Vaidya asked in an interview with the Post.

.jpg)

Is the basic infrastructure in place?

Nepal ranks 130th out of 190 countries in terms of infrastructure availability, the worst in South Asia, according to the World Bank.

Electricity and roads are particularly large infrastructure constraints compared to regional and structural peers but lately there has been a marked improvement in electricity supply while the condition of roads continues to remain poor. Poor road infrastructure thus has a big impact on both the competitiveness and spatial concentration of economic activity.

Continued poor condition of transport infrastructure is one of the reasons why Nepal was ranked 114th in the global ranking of 167 countries in the Logistics Performance Index-2018 of the World Bank. “Nepal has to compete with countries like India and China, which have far better infrastructure to attract FDI. So it has emerged as a big challenge in attracting FDI,” said Shankar Sharma, former vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission.

How does red tape hit investor confidence?

Arghakhanchi Cement sought approval from the Industry Ministry for issuing bonus shares to reinvest in expanding the capacity of the factory last year.

Pashupati Murarka, one of the directors of the company, said that the ministry didn’t approve the plan for more than a year despite receiving all necessary documents. It is the company where India’s UMA Cement International also has investment. “So we decided to distribute cash dividend from our profit recently,” he said.

Gandhi Pandit, a corporate lawyer whose law firm Gandhi and Associates handles the legal affairs of the Sinohydro Corporation Limited, a Chinese company, said that the Chinese company failed to get 35 ropanis of land in Lamjung required for setting up the security structure for the 50-megawatt Upper Marshyangdi Hydropower Project for long.

“The Cabinet didn’t take the decision for three years since the request was made even though the project started generating electricity since 2016,” said Pandit.

Nigeria’s Dangote Cement, which got approval for the highest FDI in the cement sector ($550 million) in 2013, failed to get limestone mines for six years in the lack of facilitation from the government. The company is now reportedly preparing to exit the country.

Industrialists and experts say there is a tendency of seeking a cut for the facilitation of investment. “As per the law, government officials not providing services in time is also a type of corruption. But I have not heard about the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority taking action against those whose inaction affected the works,” said Murarka, who is also a former president of the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

Pandit agrees that the bureaucracy prolongs the procedure intentionally so that they could receive the graft. “Investment in any big project is hardly approved without bribe,” he said. “Such tendency is discouraging foreign investment.”

According to Transparency International, Nepal fell two notches to 124th in the global corruption percent index in 2018 out of 180 countries surveyed, becoming one of the most corrupt countries in the world.

Are the policies and laws favourable?

The government has introduced a number of laws to attract domestic and foreign investment in the country. The new Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act, amendment to the Industrial Enterprises Act, Special Economic Zone Act and Public Private Partnership and Investment Act came into force in the past two years.

But experts and industrialists say the legal reforms alone would not help in attracting FDI. The government has also announced several incentives through these laws for attracting FDI. One measure is the government’s decision to provide electricity and access road for a cement industry.

“But Hongshi Shivam Cement, one of the largest foreign investors, has not got electricity from the government yet and the company itself was forced to build the road to reach the project site,” said Murarka. “If the government cannot fulfil its own promises, how could foreign investors be convinced to come here?” asked Murarka.

Questions have also been raised over the negative list where foreign investment has been curtailed with a threshold.

The World Bank said foreign ownership limitations, sectoral caps and a long negative list have hampered FDI inflows into Nepal.

The new law bars FDI in the areas of poultry farming, fisheries, bee-keeping, fruits, vegetables, oil seeds, pulses, dairy industry and other sectors of primary agro-production which were not barred earlier. The government recently revised the minimum threshold for foreign direct investment to Rs50 million from Rs5 million.

“These restrictive policies could affect the FDI,” said Shankar Sharma, former vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission. “At least agro processing should not have been put into the negative list.”

He said that the upward revision in minimum threshold could affect FDI in the areas of information technology and challenge funds for innovative work.

Another area where reform is needed, according to Sharma, is the practice of imposing conditions while issuing the licence for certain projects. “As every condition to be fulfilled by the foreign investor is clearly written in the laws and rules, why should we put various conditions on investors again?” Sharma asked. “Such conditions are also non-transparent.”

Do labour issues persist?

In 2014, the government and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), a United States Government aid agency, identified four main constraints to growth in Nepal: (1) policy implementation uncertainty due to political instability; (2) inadequate supply of electricity; (3) high cost of transportation; and (4) challenging industrial relations and rigid labour regulations.

When it comes to labour relations, there has been a marked improvement in labour relations with labour unrest hardly reported nowadays. Particularly, some flexible terms for hiring and firing workers and their social security helped improve the labour relations, according to experts and industrialists.

But the World Bank stated in its last Doing Business Report that Labour Law-2017 puts more burden on the employer. “The provisions of labour gratuity, medical insurance and accident insurance paid by employers place a larger administrative burden on companies that already face considerable bureaucracy,” the report states.

This provision, along with the difficulty in paying taxes, was pointed out as the major reason behind Nepal’s five-place slip in Doing Business Index in 2018. But for former NPC vice-chairman Sharma, labour unrest is no longer a big issue for investment in Nepal. “The bigger issue is the low productivity of Nepali labour force and high wages compared to that in Bangladesh in South Asia,” he said. “So increasing productivity is essential by producing skilled labour force to attract more FDI.”

Are things getting better?

Nepal has jumped to an all-time high of 94 among 190 economies in the World Bank’s ease of doing business rankings, on the back of improved credit information availability, easier cross-border trade, and enforcement of contracts. It is the biggest leap—of 16 places—the country has made in over a decade in the rankings, according to a recent report.

Economists praised the government’s efforts towards fast tracking the procedure. But economist Chandan Sapkota doubts whether procedural changes alone would drive investment growth.

“The report measures procedural changes but not the quality and efficiency of the implementation of structural reforms in tax regimens and in starting a business,” he told the Post recently.

Another economist Bishal Chalise also pointed out that serious problems like corruption are not covered by the report. “The report does not account for the level of corruption and the existing level of investor confidence, which are major factors affecting the investment climate,” Chalise told the Post recently.

8.79°C Kathmandu

8.79°C Kathmandu