Money

Surging trade deficit is cause for concern, but it could be turned into opportunities

There are several areas where Nepal can cash in on to boost domestic businesses, analysts say

Rajesh Khanal

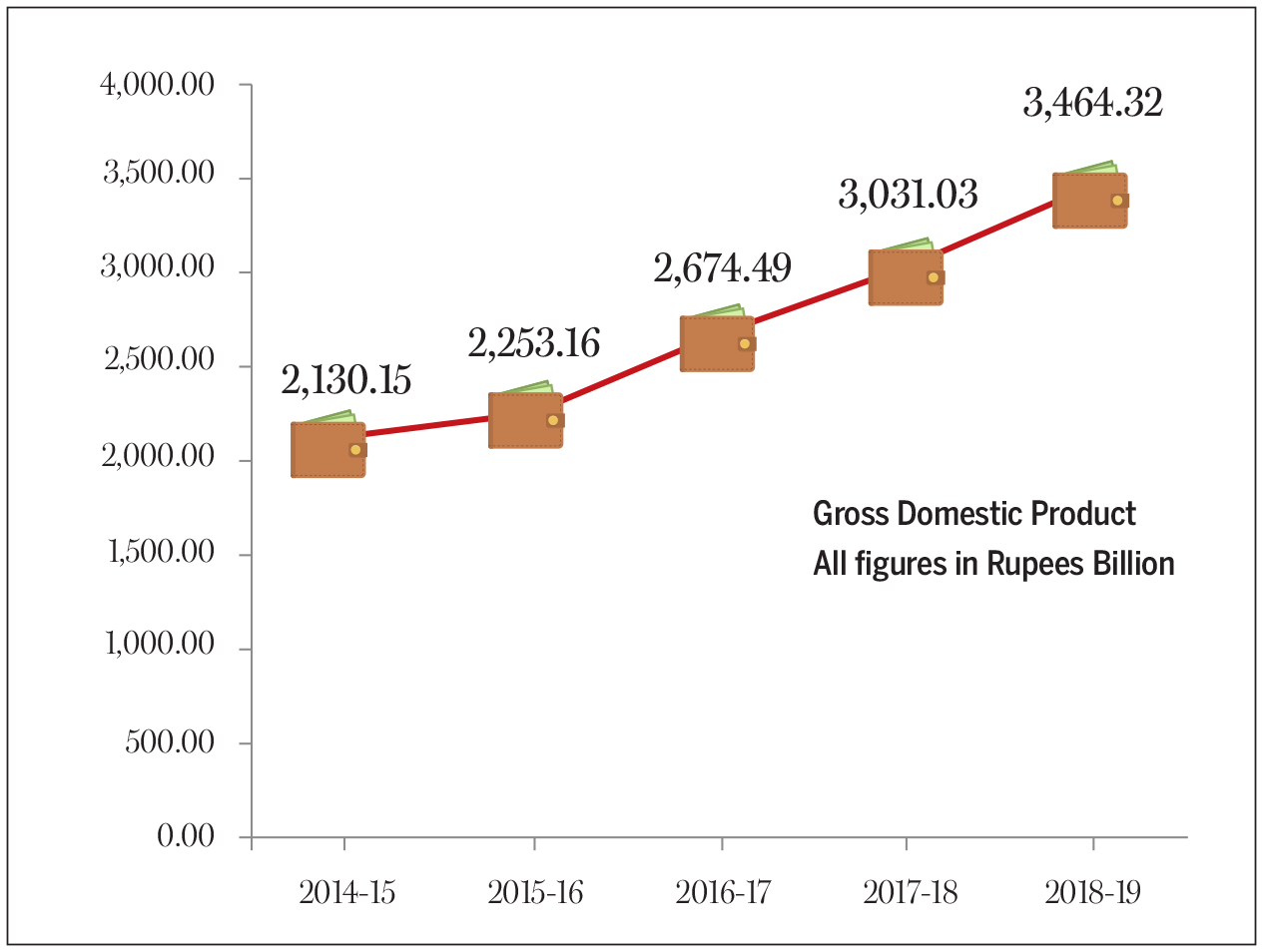

Nepal has been buying way more than what it has been selling. Import bills have been surging, while the earnings from exports have been nominal and this has led to the country’s trade imbalance grow to double in the last five years.

The Current Macroeconomic Situation published by the Nepal Rastra Bank shows that the country’s trade deficit in the fiscal year 2018-19 stood at Rs1.32 trillion, up from Rs689.36 billion in 2014-15. The year-on-year growth in imports has been 13 percent annually while the growth in exports stands at a mere 2.5 percent a year.

Economists and trade analysts say these numbers can be scary but a country needs to analyse its trade deficit through various angles, and the government through its policy interventions must try to find out how the imbalance could confer positives as well.

“Rise in import should not be always considered bad,” said Jib Raj Koirala, former joint-secretary at the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies. “Increase in import is a normal phenomenon.”

According to Koirala, since more import also indicates an increase in people’s purchasing power, the country also needs to look whether it has been able to create ample room for entrepreneurs to tap the opportunity. And here’s where the government needs to focus: for what kind of goods the country is paying and the types of items it is selling to earn foreign currency.

Of all the goods that Nepal imports, petroleum products, vehicles and spare parts, agricultural products and iron and steel products hold the largest shares. According to Koirala, Nepal can minimise the import of petroleum products by producing alternative energy while the import of agriculture products can be substituted by improving productivity inside the country. The share of petroleum products was 15 percent and that of agricultural products was 15.5 percent in the total import bills last year.

“We can do little to reduce the import expense on machinery parts and iron and steel products,” said Koirala. But the country can still do better if it can cut down on imports of goods that can be manufactured at home, thereby boosting the industrial and manufacturing sectors.

Nepal also spends a staggering amount of money on packaged foods and other consumer items, which can be produced at home. The country imported sweet biscuits, potato chips, chewing gum, chocolate, soft drinks, pan masala, dalmot, salted bhujiya, waffles and wafers, bakery products and other packaged snacks worth Rs11.96 billion in the last fiscal year against the import of Rs10.6 billion in 2017-18, according to the statistics of the Department of Customs.

Such products, according to analysts, can be manufactured in the country, but it has not happened largely due to a number of adverse factors that prevent business houses from investing money in this sector. This has shifted the opportunity to foreign producers to penetrate the market and benefit accordingly.

.jpg)

The government, according to Koirala, however, can make some policy interventions to promote industries and entrepreneurship so that trade deficit can be turned into opportunities by creating an environment for industries and manufacturers to produce quality goods and services at home.

“The government should be able to cash in on people’s increased purchasing power and introduce policies to promote entrepreneurship in the sectors which can easily fulfil the domestic demand,” said Koirala. “With an improvement in purchasing power and change in lifestyle, it will be a challenging task to reduce consumption expenses of the people. It calls for state policies to enhance exports.”

At the Trade Policy Review held in December at the World Trade Organization, the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies had acknowledged that Nepal could not utilise properly the privileges accorded to it as a least developed country of the multilateral organisation in the global markets. The ministry had underlined the problem for failing to improve the quantity and quality of exportable goods.

The soaring trade deficit was also due to a growing dependency on India, with which the country conducts almost two-thirds of its trade. The statistics show trade deficit with the southern neighbour has increased from Rs435.8 billion to Rs855.17 billion in the last five years.

Analysts also point out a number of factors responsible for the country’s poor performance in trade. Small export basket, lack of improvement in quality, high production costs and existence of non-tariff barriers with India, in particular, are also to blame for slow growth in the country’s export. In addition, weak trade logistics that include poor physical infrastructure and administrative set-up have been hindering the country’s export.

According to Chandan Sapkota, an economist and a senior fellow at Nepal Economic Forum, trade deficit for a low-income country like Nepal is not unusual. “Nepal does have a huge potential to accelerate its economic activities. This situation of trade as well as current account deficits today, however, are normal,” said Sapkota.

When it comes to Nepal’s exports, the scenario is quite bleak.

Among the export items, palm oil holds the largest share of 10.6 percent (Rs10.33 billion). Since Nepal does not produce palm, the earnings made from export of palm oil raise many an eyebrow.

The share of woollen carpet was 7.6 percent of the total export of Rs97.10 billion, while those of polyester yarn and jute items were 6.3 percent and 6 percent respectively.

Trade expert Purushottam Ojha, who served at the Ministry of Commerce for one and a half decades in the capacity of joint-secretary and secretary, said checking the import at present could give rise to anomalies such as smuggling.

“There is no way out other than increasing production volume for both import substitution and export promotion,” said Ojha.

Unless issues like poorly performing manufacturing sectors, low agricultural productivity, shortage of skilled manpower and poor infrastructure are addressed, Nepal will continue to struggle to manage its import bills.

Although the government has made attempts to address the issues by enforcing a number of measures, their impact in lessening the deficit has been almost negligible.

Recently, Nepal signed a mutual recognition agreement with India that has given a way out to locally produced food tested in the Nepali laboratories to access in the Indian market.

Two months ago, the government unveiled a national work plan, a long-term perspective vision of the government to substitute imports and give priority to domestic production. Tightening of the trust receipt loans for vehicles importers is one of the measures that the work plan is enforcing to check import of luxury goods, including high-end vehicles, in a move that is expected to boost not only national savings but also ensure the availability of capital for investment in the country, according to officials at the Ministry of Commerce and Supplies.

While revising the Nepal Trade Integration Strategy in 2016, the government had also raised the export incentives up to 5 percent from 2 percent. However, the export of high potential goods could not pick up pace despite the government move. Citing the country’s trade as being multi-disciplinary, the government has also tried to introduce reform measures in the legal framework.

Over the last five years, Nepal has endorsed the Nepal Electricity Regulatory Commission Act, Power Purchase Guideline, Guidelines for the Development of Grid Connected Alternative Energy, Trade Policy 2015, Anti-dumping Act, Industrial Enterprises Act 2016, Companies Act 2017, Foreign Investment and One-Window Policy 2015 and National Tourism Strategy 2016-25, among others.

“But laws, regulations and policies alone won’t help,” said Koirala. “Strict implementation is a must. Unless the rules and guidelines are enforced, government efforts cannot produce rewarding results.”

According to Ojha, the government should create ample opportunities for exporters so that they can reach out to various other countries that have been providing duty-free access to Nepali products.

“The government has to create a conducive environment through the implementation of suitable policies and incentives to the investors,” said Ojha. “And again, if imported goods are being absorbed, it means our purchasing power has gone up. This is a clear indication that the country’s private sector has been unable to tap a larger portion of business opportunity within the country.”

Analysts agree that a trade deficit is not always a bad thing. However, they caveat it with a number of factors: the situation of the country, government’s policy interventions, the duration and size of trade imbalance, the environment for domestic businesses and manufacturers and the country’s economy, among others.

According to Sapkota, a trade deficit can be considered positive if it is due to imports of capital goods or intermediate goods that help boost competitiveness in terms of price and quality.

“However, we need to be mindful higher imports leading to import-substitution and higher exports in the medium-term are suitable provided that we are able to produce goods competitively and find markets for them,” said Sapkota. “Moreover, the government needs to discourage imports of non-essential goods and services to lower import bill in the short-term.”

21.11°C Kathmandu

21.11°C Kathmandu