Money

Nepal needs Rs1,770b annually to meet SDGs

The government’s revenue and private sector investment will not be sufficient to attain the United Nations-backed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, which implies Nepal’s dependence on foreign aid will go up sharply in the coming years, a latest report says.

The government’s revenue and private sector investment will not be sufficient to attain the United Nations-backed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, which implies Nepal’s dependence on foreign aid will go up sharply in the coming years, a latest report says.

Nepal will have to fork out about Rs1,770 billion per year till 2030, or around 68 percent of the last fiscal year’s gross domestic product (GDP), to attain the SDGs, says the report, ‘Sustainable Development Goals - Status and Roadmap: 2016-2030’, which highlights major issues and challenges that the country needs to reckon with to implement SDGs.

A big chunk of this investment, or 55 percent, will have to come from the government, adds the report released on Sunday by the National Planning Commission (NPC) Vice Chairman Swarnim Wagle. This investment, which hovers around Rs973.5 billion per year, is around 76 percent of the government’s budget for the current fiscal year.

Most of the public investment will go towards poverty reduction, followed by agriculture, health, education, gender, water and sanitation, transport infrastructure, climate action, and governance. The public investment requirement is expected

to be the lowest in tourism followed by energy, industry, and urban infrastructure, mainly housing, where private and household investment will be required.

The private sector is expected to contribute about Rs382 billion per year to meet the SDGs and households are expected to finance up to 5 percent of the total SDG investment requirement, which comes to around Rs88.5 billion per year. The incremental financing resources of cooperatives available for SDGs, according to the NPC report, are estimated at about Rs25 billion annually, while NGOs are expected to mobilise about Rs20 billion per year to meet the SDGs.

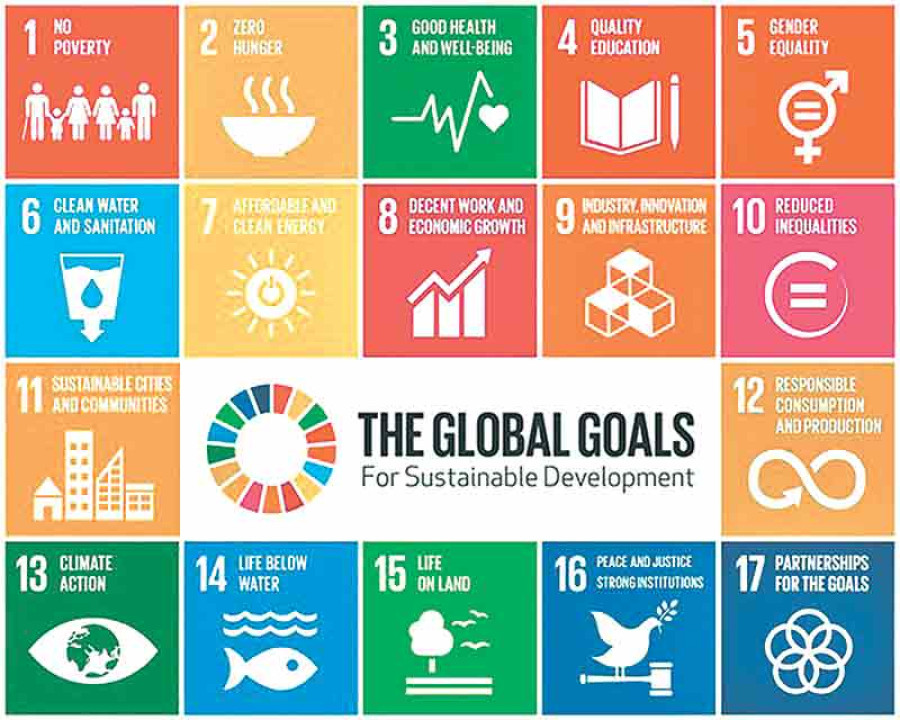

SDGs-a follow-up on Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which expired in 2015-are a set of 17 goals and 169 targets covering a broad range of sustainable development issues. One of the primary objectives of SDGs is to end poverty and hunger from the world. SDGs also aim to promote well-being of all the people, sustainable industrialisation, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, and employment and decent work for all. Other goals include: reducing inequality; making cities inclusive, safe and resilient; ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns; and taking urgent actions to combat climate change and its impacts.

In short, SDGs aim to bridge inequality of all forms, raise access to basic public services, ensure access to justice, protect the environment and promote sustainable economic development. These characteristics make SDGs a noble concept. But these goals are not as easy as MDGs to attain.

“During MDGs era, it was easy to earmark a larger percentage of government budget to basic social services. But for SDGs, it is difficult, and perhaps not credible, to switch resources from economic sectors to social sectors, as the former is as important as the latter in the menu of SDGs,” says the report.

This implies arranging funds to meet SDGs will be a tough nut to crack for the government. The NPC has said domestic financing through revenue mobilisation and internal borrowing could finance about 62 percent of the public sector SDG investment requirement while foreign aid, both grants and loans, would finance another 20 percent of the public sector financing needs if the overall foreign aid pie grows by at least 10 percent during 2016-2020 period, 5 percent during 2021-25 and 2 percent thereafter. This means inflow of foreign aid will have to double from existing levels to meet the SDGs, which will raise country’s dependence on overseas development assistance (ODA).

“While higher amounts of ODA are needed to bridge the financing gap, no distinction should be made between funding capital and recurrent costs through ODA, since the country cannot afford to fully fund recurrent expenditures which account for a large share of total cost in health, education and agriculture, among others,” says the report, which has identified infrastructure as the sector that will face the largest financing gap. “To maintain macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability, a growing share of ODA will need to flow in the form of grants.”

It appears there is no alternative for the country other than relying on foreign aid to meet the SDGs, because the funding gap is so huge “a substantial increase in domestic resource mobilisation by the government will still be insufficient to finance SDG investment requirements in the medium run”. Overall, the financing gap for SDG implementation, as a share of GDP, ranges between 9 percent in the 2016-2019 period to a high of about 15 percent in the last leg, 2025-2030. The average financing gap hovers around 12 percent of GDP if real economic growth ticks 6.6 percent per year throughout 2016-2030. If the economic growth follows a sub-optimal path of 5 percent, the financing gap will further widen. This calls for higher expenditure efficiency, which can widen fiscal space for SDG implementation. “Efficiency gains need to be weighed against distributive priorities as the SDG mantra is to leave no one behind,” adds the report.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu