Money

Economy cannot tolerate inflation of over 6.4pc: NRB

Prices of goods and services should not rise by more than 6.4 percent per year if Nepal wants to maintain price and financial stability, and ensure economic growth and currency peg with India do not come under pressure, the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) has said.

Rupak D. Sharma

Prices of goods and services should not rise by more than 6.4 percent per year if Nepal wants to maintain price and financial stability, and ensure economic growth and currency peg with India do not come under pressure, the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) has said.

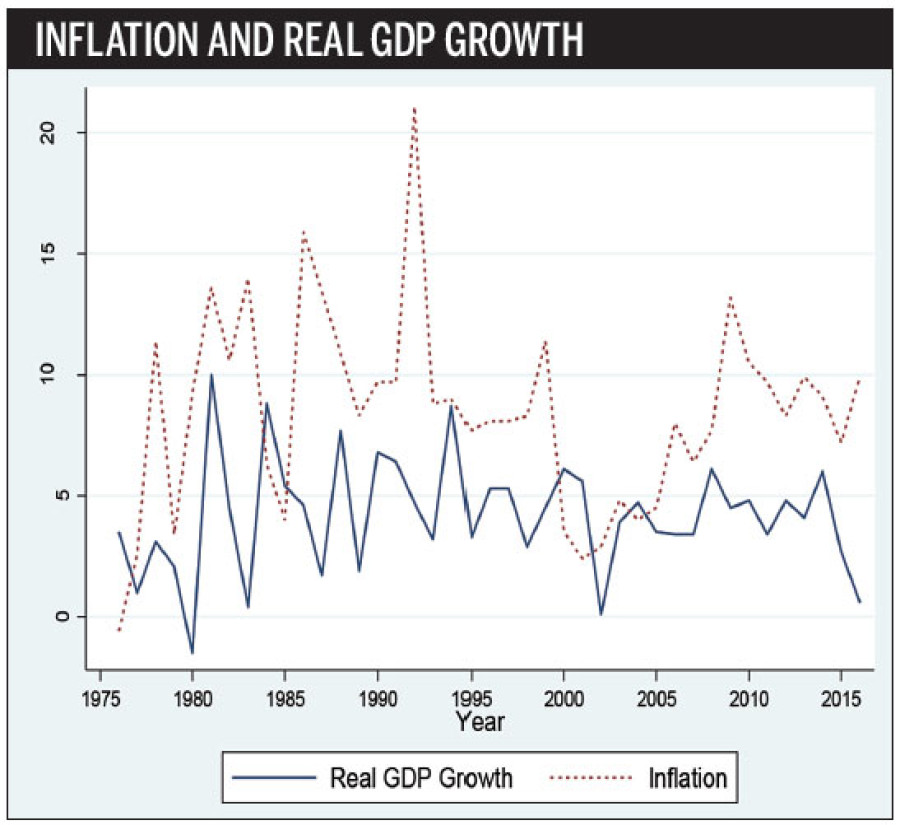

A study conducted by the central bank using two methodologies showed that inflation should be contained between 6.3 percent and 6.4 percent, indicating the need to make monetary policy robust so as to put a lid on prices that fly through the roof. Inflation has historically remained at a higher level in Nepal, with prices of goods and services going up by an average of 8.8 percent per annum in the last five years. This inflation rate, which is among the highest in South Asia, is 1.3 percentage points higher than the estimate of the central bank.

“High inflation distorts the optimal allocation of resources and retards growth, weakens the external competitiveness, and lowers the domestic financial savings, among others,” says the NRB working paper titled ‘Optimal Inflation Rate for Nepal’.

The central bank fixes annual inflation target through monetary policy launched at the beginning of every fiscal year. But adequate policies and instruments are not introduced to meet the target. This is an indication that the monetary policy is framed on an ad-hoc basis.

“We want an end to this practice,” said Nara Bahadur Thapa, executive director of the Research Department at the NRB. “To begin with, we will fix optimal inflation rate, which will help us contain inflation at a certain level. The monetary policy will then be used to attain the target.”

Although the working paper launched by the NRB has said the economy can tolerate inflation of up to 6.4 percent, it is not known whether the central bank will use this figure as optimal inflation rate.

“We’re currently doing a study. We’ll finalise the rate once we complete the study on output gap-the gap between potential gross domestic product (GDP) of the country and the actual GDP,” Thapa said without elaborating.

These initiatives taken by the NRB, however, should not mean the central bank is planning to adopt inflation targeting as a monetary policy strategy, Thapa added.

Nepal has never taken concrete steps to contain hikes in consumer prices because authorities believe inflation here is derived from India. This means Nepal, a net importing country, also imports inflation from India because over 60 percent of the country’s imports come from the southern neighbour.

This is true. But over the years difference between inflation in Nepal and India is widening.

Inflation wedge with India, for instance, widened to 6.4 percent in January largely because of supply disruptions created by trade blockade imposed by India. In that month, inflation stood at 12.1 percent in Nepal, while consumer prices had gone up by only 5.7 percent in India.

Since then the inflation gap has narrowed and dropped to 0.8 percent in April. But over the period inflation in Nepal has run 2–3 percent higher than in India, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). “This has led to real appreciation of Nepali rupee,” Andreas Bauer, senior resident representative of the IMF for Nepal, Indian and Bhutan, told the Post last week. This has exerted pressure on currency peg that Nepal has maintained with India.

Nepal has maintained a currency peg of Rs1.6 with India. This is the nominal exchange rate.

“The sustainability of the peg crucially depends on keeping the inflation rate close to that of India,” NRB working paper says. It is important to keep inflation gap closer because wider difference indicates same good or service is expensive in Nepal than in India.

For example, if a good costs IRs100 in India and Rs160 in Nepal, purchasing power parity of Nepali and Indian rupee is said to be the same. But if the same good costs IRs100 in India and Rs200 in Nepal, Nepali currency, in real terms, gets overvalued by 25 percent. In that case, it would make more sense to purchase goods in India and bring them to Nepal rather than purchase those available in the country.

This eventually exerts pressure on foreign exchange reserve because every time people visit India to purchase goods, the central bank will have to sell dollar and purchase Indian rupee to provide exchange facility.

Whenever demand for currency rises in this manner, the nominal exchange rate-which is Rs1.6 for every Indian rupee-gets a jolt. But that won’t happen here because the currency is pegged. Yet divergence in prices hits the real exchange rate and leads to real appreciation of currency. Of course, factors such as tax rates and transportation costs determine cost of goods in any country. But the basic principle is that whenever there is divergence in real exchange rates, currencies come under pressure.

This is the reason why the IMF, in its latest Article IV Consultation Report, has called on the central bank to adopt “a medium-term inflation objective consistent with eliminating the inflation wedge with India”.

31.5°C Kathmandu

31.5°C Kathmandu