Money

Interbank lending rate up despite excess liquidity

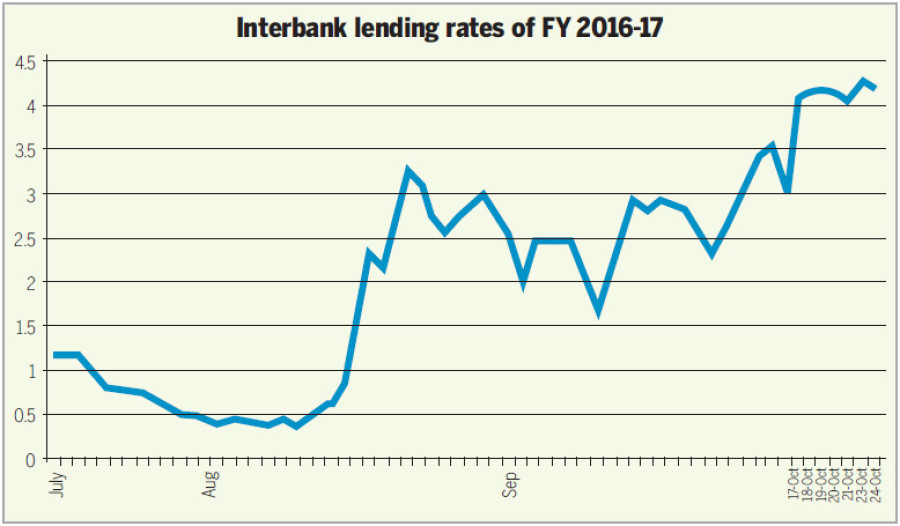

The average interbank lending rate of commercial banks has stood at over 4 percent for at least a week despite excess liquidity in the banking sector, as banking institutions have started witnessing a mismatch in their asset and liability positions.

Rupak D. Sharma

The average interbank lending rate of commercial banks has stood at over 4 percent for at least a week despite excess liquidity in the banking sector, as banking institutions have started witnessing a mismatch in their asset and liability positions.

The statistics of Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) show that the interbank lending rate, or the interest rate at which banks lend to one another, fluctuated within a band of 1.7 percent and 3.5 percent throughout September.

From the beginning of October, however, rates started going up, with the average rate moving within a band of 4 percent and 4.3 percent for more than a week now. The weighted average interbank lending rate of commercial banks stood at 4.2 percent on Monday.

Interbank rates generally go up when the banking sector faces a liquidity crunch. But this is not the case at the moment, as excess liquidity in the banking sector currently stands at around Rs40 billion, according to the central bank.

“The problem, it appears, is an asset-liability mismatch among banking institutions which is exerting pressure on interbank rates,” a senior NRB official told the Post on condition of anonymity.

Interbank borrowings generally take place to manage short-term liquidity problems, such as a shortfall in the cash reserve ratio, which is the portion of total deposits that banks must park at NRB. Such borrowings mature within a week, meaning the liability lasts only seven days.

But some banks, according to the NRB official, have borrowed money using the interbank platform and converted it into long-term loans.

“This borrowing largely took place when rates stood at less than 1 percent as banks were awash in liquidity,” the official said, referring to the interbank rates before August 15.

“Banks resorted to this measure because it was cheaper to borrow money from other banks and convert it into loans than convert deposits into loans, as deposit rates were way higher than interbank rates.”

This means that money which needed to be returned after seven days was converted into loans—or assets—which are generally returned by borrowers only after a year or more.

“Despite knowing that conversion of short-term liabilities into long-term assets would create an asset-liability mismatch, banks assumed they’d be able to handle the situation by attracting more deposits at a later date,” the official said.

But over the months, deposit collection of commercial banks has started trailing behind credit disbursement, which dashed their hopes of mobilising additional deposits at a later date.

In the first two months of the current fiscal year, for instance, bank deposits swelled 79.6 percent year over year, according to the latest NRB report.

However, credit expanded a whopping 449 percent, mostly to finance imports for Dashain, during the same period (between mid-July and mid-September).

Meanwhile, government revenue has not been well spent, resulting in a treasury surplus of around Rs184 billion. This means a huge chunk of money that should have entered the banking sector is locked up in the state coffers.

Also, NRB mopped up over Rs49 billion in excess liquidity from the banking sector towards the end of the last fiscal year using a one-year money market instrument called NRB Bond, which tightened the liquidity position of many banks.

Then, with the advent of the new fiscal year in mid-July, NRB used more instruments to absorb excess liquidity to set the newly launched interest rate corridor into motion, which also lowered the amount of cash available to banks.

“Amid this situation, banks that converted interbank borrowings into loans are being compelled to renew credit that matures after a week at higher rates because of a relatively low growth rate of deposits,” the official said, adding that interbank rates were rising because of short-sightedness among banks.

9.25°C Kathmandu

9.25°C Kathmandu