Miscellaneous

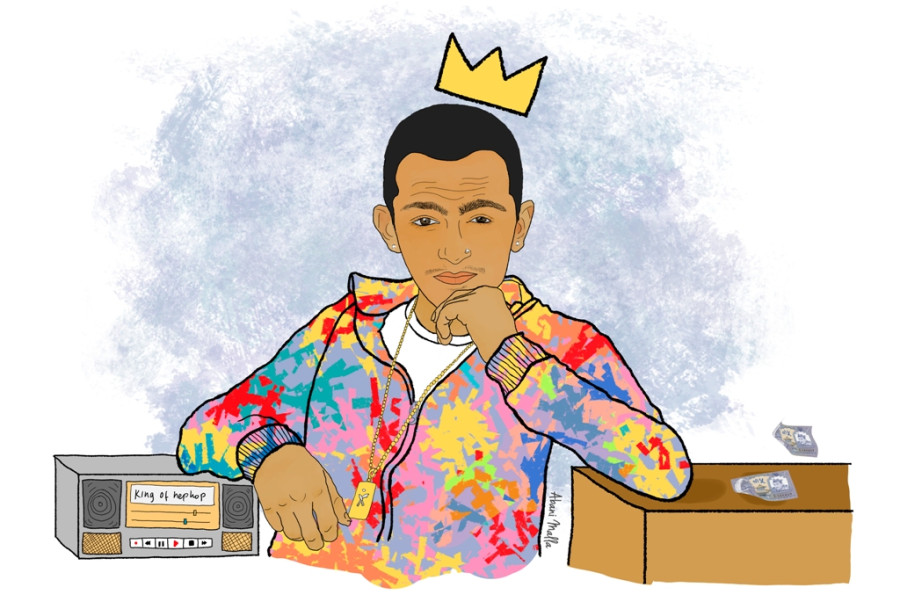

From a meme to King of NepHop, Lil Buddha is making a comeback

For rap aficionados, Sacar Adhikari lies somewhere in the middle—there are artists better than him and artists worse than him. He’s back, he’s better, but some listeners say he’s not the best yet.

Abani Malla

Sacar Adhikari is angry. He’s shirtless, tattooed and he’s cursing. He’s live-streaming on his Facebook page and within minutes, hundreds of people are watching the video. Sacar is attacking everyone, from then Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal to rapper Laure.

In 2017, videos recorded from Sacar’s Facebook livestream went viral, effectively turning him into a meme. Within the span of a day or two, 22-year-old Sacar went from being semi-popular to downright infamous. He’d asked his fans to shoot Laure with a ‘katta’, an improvised pistol, in return for a ‘heera’, a diamond. People on the internet lost it.

Over a year later, hands folded at the back, Sacar stood in front of a mic, wrapped in a thick winter coat with a fur collar. Even though he’s inside a studio, he’s wearing sunglasses that reflect the studio lights. He has a new look: he’s pierced his nose.

With Uniq Poet and G.O.D. on The Beat beside him, Sacar steps up to the mic.

“Yo, Lil Buddha on the mic, what's up, what’s up, been a long time,” he begins, announcing his comeback to the Nepali hip-hop scene, locally referred to as NepHop.

On January 12, 2019, two days before the two-year death anniversary of Nepali rap stalwart Yama Buddha, Sacar—who now calls himself Lil Buddha—uploaded ‘King of NepHop’, the first song of his upcoming album Shree Panch, to his YouTube channel. In the 10-minute-long one-take freestyle cypher, Sacar addresses his mental illness and drug use, all while proclaiming himself the greatest.

Yeah I do it for the future, psychotic rapper, psychedelic user, getting many views huh / Everybody watching going real crazy, everybody laughing / Everybody asking, what the fuck happened? / They say they see my name in them tabloids and magazines

Within an hour, the video was trending as number one on YouTube Nepal and already had 18,000 views; as of today, it has over three million views.

Since then, Sacar has started a vlog, Sacar ko Sapana, which again has accrued over a million views in just two months. His most recent vlog, with singer Neetesh Jung Kunwar, was trending at number nine on YouTube overnight.

Sacar Adhikari isn’t angry anymore. He’s successful.

Post Photo: Abani Malla

***

A few minutes have passed and Sacar is still reading the menu. At a rooftop lounge in Dillibazar, the 23-year-old rapper is not the arrogant, boastful Lil Buddha. He’s Sacar Adhikari: average height, skinny, dressed comfortably in a black tracksuit. A few minutes later, he finally looks up, and orders a cup of black tea.

But he’s still wearing the rectangular ‘King of NepHop’ gold chain from his latest music video—two khukuris crossed in the middle with a diamond above them.

Finally, he begins to talk, unhindered, as if rapping at a slower tempo. He starts at the beginning, recalling his days as a child listening to Radio Nepal with his mother during school holidays.

“He would talk so much that I’d offer him five rupees if he just stopped talking for a while,” says Radha Adhikari, Sacar’s mother. “Yet he would refuse the offer and keep asking me more questions.”

One afternoon, during a visit to his maternal home, Sacar found Saujan Sangraula—his youngest maternal uncle and a singer—ready with a guitar. His uncle’s impromptu personal performances became a crucial factor for piquing Sacar’s interest in music.

“It was cool,” recalls Sacar.

That day, Sacar went home with a few cassette tapes, hidden among which was one from GP—Girish-Pranil—one of Nepal’s first hip-hop duos. But back then, Sacar was more interested in other forms of music.

When Radha left for Norway in 2005 for work, Sacar and his family moved in with Sangraula, and the two started to explore more music together.

“When we were living together, I was exposed to someone who could write and perform songs very well,” says Sacar. “Every day, uncle and I would discover new artists. I even started to play the guitar.”

There weren’t any specific genres or artists Sacar listened to, but growing up in the 90s, he admired The Doors, Limp Bizkit, Sabin Rai, Blink-182, Audioslave, Aerosmith, Bob Marley, Iron Maiden, Metallica, Avril Lavigne, Pantera—everything that a young boy growing up in Kathmandu, exposed to the radio and MTV, might listen to.

When Radha returned from Europe in 2008, Sacar, who was now in the eighth grade, could hum Nabin K Bhattarai’s songs and perform the rap from Nepsydaz’s remake of 1974 AD’s Chudaina timro maya le.

“At first, I was surprised to see my son—this talkative boy—sing so well,” says Radha.

Sangraula, Sacar’s uncle, eventually left for Europe, but that didn’t discourage him from pursuing his music. Back then, Sacar was singing more, not rapping. His classroom was the audience and a chair his stage. By the time he was in the tenth grade, 15-year-old Sacar was performing verses he’d memorised from his favourite songs while his classmates circled him. It was also then that Sacar smoked his first joint, after his classes were over, again circled by his close friends.

By high school, Sacar’s musical tastes had changed—he had now started listening to rap. Busta Rhyme’s feature on Chris Brown’s Look at me now was one of the first verses he admired, for its frenetic pace, says Sacar. He practised and later performed the verse in front of his friends, leaving them impressed. It was this song that introduced Sacar to ‘old school hip-hop’, and soon, he was researching this global phenomenon.

“It was what hooked me into rap but oddly, later I figured that it wasn’t even real rap,” says Sacar.

***

Hip-hop in Nepal can arguably be dated back to 1993, when Girish Khatiwada and Pranil Timalsina formed GP, and a year later, released the first Nepali rap album Meaningless Rap. The 10-track album was greatly influenced by the stylistic trappings of East Coast hip-hop—primarily from New York in the United States, the birthplace of the movement. The album was full of rap cliches—drugs, love and braggadocio, as on the track Ma Yesto Chu. But they were also singing about politics and social issues. The album went on to sell more than 18,000 copies.

“Their song, Malai vote deu, was the first song about activism that I had heard,” says Sacar. The song was a satire about politicians and how they make false promises before elections. “I remember those songs as my earliest inspiration to rap music.”

Following GP’s unprecedented commercial success as a rap duo, other artists started to emerge in the Nepali rap community. By the early 2000s, there was a fully-fledged hip-hop community in Kathmandu, and they called their brand of music ‘NepHop’. Artists like Nirnaya Da’ NSK, Nepsydaz, Sammy Samrat, Madzone, DA 96, 9double7, Jehovah, and The Unity were getting regular play on the radio and on television, and they were selling out concerts.

But in the years that followed, and despite the long list of Nepali rappers, the movement failed to break through. It was almost as if rap was a blip on Kathmandu’s musical radar—there and gone. Most rappers either stayed underground or stopped rapping. Others left the country for college or to work. The few that continued were playing to a handful of loyal fans.

It was only in 2011 that Nepali rap saw a resurgence. With one music video, Yama Buddha brought rap back into the mainstream and this time, it exploded. Yama Buddha’s video for his song Saathi, off of his mixtape, gained thousands of views and elevated him to overnight rap star.

In 2012, Sacar had just graduated from high school and rap was fast becoming his obsession. He was recording himself delivering free verses over Dr Dre beats, and even filmed his first single, with the help of his sister and uploaded it to YouTube. That video got a measly 2,000 views.

“It was laughable compared to the views I get today,” says Sacar. “But it was that little success that told me to start rapping professionally.”

He had moved on from the staple hard and classic rock repertoire of the young Kathmandu man and was now listening religiously to rap. His biggest influencers were Nas, Tupac, Big L, Cassidy and KRS-One—all from the ‘old school’ of the rap game—while Kendrick Lamar, Dizzy Wright, Wax and Herbal T are among the contemporary and underground rappers he admires.

Later that year, while at a cafe for a smoke, Sacar ran into Yama Buddha. They were introduced by a common friend. Sacar knew Yama Buddha and although he acted calm when they first met, he said he was ‘impressed and had a good feeling.’

In early 2013, a few months after they met, Yama Buddha, in collaboration with three friends, started Raw Barz, a freestyle battle league where rappers would go head-to-head against each other in insults. Raw Barz soon turned into a platform for young Nepali rap artists to show up, perform and test their mettle.

A few months after their first meeting, Sacar received a message from Yama Buddha, inviting him to take part in the first season of Raw Barz.

The scene is set: Sacar on one side and Uniq Poet on the other. They’re surrounded by a hooting, booing audience. Yama Buddha motions for quiet. They toss a coin and Uniq goes first.

This was the first time Sacar met Utsaha ‘Uniq Poet’ Joshi, who he’d go on to collaborate with later. Although they went to the same school, they had never known each other.

“I had battled before, but it was Sacar’s first time,” says Joshi. “Then, it was easy for me to tackle him, but now he’s gotten quite good at it.”

The first few days, Sacar sneaked out of the house to attend the event. Later, as his videos went viral, his mother learned of his activities.

“I was fine with the rap, but I asked him to stop using such language,” says Radha. “But he told me this is how it is.” Since it was a rap battle, insults and coarse language were common at Raw Barz.

Sacar’s father, Keshab Adhikari, was also supportive.

By the end of the first season of Raw Barz, Sacar had won a small but growing fan following and had built connections with the Nepali rap community, especially Yama Buddha, or ‘Yama dai’ as he calls him. Yama Buddha was a mentor to many newcomers in the rap game and Sacar, too, placed him on a pedestal once he got to know him well.

In February 2015, Sacar left for Australia to continue his studies. He enrolled at the University of Technology Sydney for Information Technology, but a year later, he dropped out and started working full-time delivering mail. He liked his job, as he owned a bike and could listen to music all day. He also had occasional gigs at bars and restaurants. Sacar was busy.

At the end of 2016, things went sour between Sacar and his then girlfriend, which he said began affecting his emotional health. The Post reached out to the former girlfriend but she refused to comment or be identified.

On January 14, 2017, Sacar returned to his apartment from work, only to hear the news of Yama Buddha’s suicide at his home in London. The entire Nephop community was shaken. And Sacar lost his mind.

Sacar was suffering the emotional hurt of his failed relationship, and the mental pressure of living and working in Australia. Yama Buddha’s death was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

“I stopped caring about anything, nothing mattered anymore,” says Sacar.

He started doing psychedelics and hard drugs. And within a few weeks, he started going online on Facebook, streaming videos of him spouting conspiracy theories and asking for hits on other rappers. He was angry, harsh and not in the right state of mind. He blamed other rappers for Yama Buddha’s suicide and even abused his own sister. His mother, back in Nepal, started receiving phone calls and visits from friends and relatives. Sacar had lost control.

“I remember doing those things,” says Sacar. “But I can’t figure out how I was doing it. I just know that I wasn’t sane.”

Sacar with Girish Khatiwada of GP, Nepal’s pioneering rap duo. [Photo courtesy: Sacar Adhikari]

***

Sacar admits he is stubborn. Once he plans to do something, he says he doesn’t listen to anyone, especially when he’s intoxicated and out of his mind. In the midst of his breakdown, Sacar somehow managed the time to record a new album. He felt the need to complete his dream of ‘paving the roads of NepHop’, abandoned halfway due to the death of Yama Buddha.

In 2017, he acquired a new stage name, Lil Buddha as a tribute to Yama Buddha.

“In hip-hop, the day you name yourself, you become a man,” he says. “It’s not about the gender, it’s about an attitude.”

In August of that year, he dropped his first mixtape, Tathastu, with the track Sapana, a remake of Yama Buddha’s original.

“To me, Sacar is a rebel. His cover of Yama Buddha’s ‘sapana’ was what caught my ear,” says 20-year-old Gaurav Phuyal, a frequent commenter on Sacar’s Instagram who’s already pre-ordered his new album. “I love the reggae vibes in songs like Ganja Nation.”

Although Sacar’s album was out, he was still on drugs. His parents, desperate back home, requested his friends to take him to a hospital. Radha even acquired a visa in two days and flew to Sydney to take care of her son. Sacar was medicated but even the doctors weren’t sure what, if anything, was wrong with him.

“They said he might have bipolar disorder,” says Radha. “But they couldn’t confirm it.”

Sacar was prescribed medication for depression and eventually discharged. He returned to Nepal with his mother later that year. But back home, another crisis awaited him.

His livestreamed rants had reached a wider audience than he’d imagined. He’d railed against the prime minister and other politicians, leading the police to file a cybercrime case against him. If convicted, he could have received five years jail time and a fine of Rs 100,000, says Radha.

Sacar’s parents argued that their son wasn’t mentally stable but this meant that he’d have to undergo a medical evaluation. Sacar was hospitalised at the mental hospital in Patan for a week. But it wasn’t doctors who gathered outside his room every morning—it was the group of female interns who apparently knew of Sacar and were fans of his music. They mobbed him during his stay in Patan, asking him for autographs and selfies. Radha captured her son’s newfound fame on video.

Sacar was eventually found not guilty since he’d been under the influence and had not been mentally stable. But the whole process had taken a toll on him. For most of 2018, Sacar stayed home, waking up late, taking a shower, and then sleeping all day. Healing took time, and Sacar invested almost a year in getting better. But when 2019 dawned, he knew he had to get back into the game.

Sacar registered a new record label, YB (Yama Buddha) Records, and has geared up to release a new album under it.

“I wasn’t silent, I was working in silence,” he says. “I had it all planned out because Lil Buddha had to build his empire.”

He came up with the King of NepHop brand, managed by YB Records, which primarily does “rap stuff”—releasing songs, organising rap battles, freestyle sessions and hosting interviews. Sacar wants to “take over” the kingdom that is hip-hop in Nepal.

His process is regimental and old-fashioned. Sacar has his own flag, literally, and an album that he says will be circulated (sold) like currency.

This new album, Shree Panch, was announced in December 2018 on Sacar’s Instagram. He has a unique concept for the new album—he’s printed a one-rupee note with King Birendra on the left and himself on the right, and a QR-code on the back, encouraging buyers to directly download the album.

Promo image from Sacar's new album -Shree Panch.

“I love how Sacar is focused on his dream. He messed up a little when he was in Sydney but I think the pressure that international students, particularly one with a background like his, might’ve taken a toll on him,” says Prisma Aryal, a music student and a long-time fan. “The way he can smoothly transition from pop and jazz influenced songs to rap shows that he’s tremendously multi-talented.”

But not everyone likes Sacar’s new direction. His critics, and even fans, feel “less connected to the song as the lyrics were wack and had no substance,” says Phuyal. Sacar’s constant cry to “save Nephop” had fans expecting that he’d be more “like Yama.”

Nephop isn’t as popular as hip-hop is in the west, but the community is growing, especially since the Raw Barz series. For rap aficionados, Sacar lies somewhere in the middle—there are artists better than him and artists worse than him. He’s back, he’s better, but some listeners say he’s not the best yet.

“He’s better than he was before, but like in King of NepHop, he gets outshone by others,” says Dirghayu Shah, a rap fan. “But if you’re into the genre then he’s like another brick in the wall, nothing special.”

Sacar has plans to make the industry bigger and better but most importantly, he aims to ‘pave roads’ for emerging rappers, just like Yama Buddha wanted to. His time in Australia helped him acquire a new perspective.

From the rooftop lounge in Dillibazar, Sacar looks out at a panorama of his city while the wind blows out his cigarette. He says he looks forward to many of his plans, especially his Nepal tour, which he hopes will promote NepHop in every corner of the country.

“I don’t really see a future for Sacar in rap,” Radha, his mother, says. “But then again, I don’t see my headstrong son doing anything else.”

Sacar with Yama Buddha, the rapper who was a mentor to many newcomers. [Photo courtesy: Sacar Adhikari]

12.73°C Kathmandu

12.73°C Kathmandu