Miscellaneous

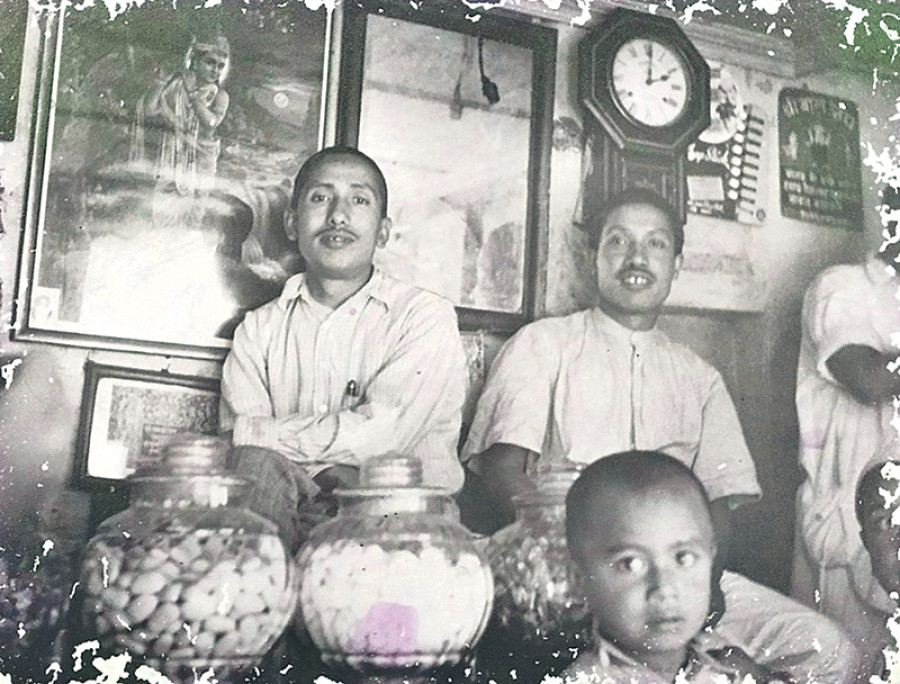

Tilauri Maila and Kanchha Dai: Kathmandu’s first tea sellers

Mangsir-Paush, the peak of Kathmandu’s winter—so cold that even the fish take shelter beneath rocks. 3 am.

Prawash Gautam

Mangsir-Paush, the peak of Kathmandu’s winter—so cold that even the fish take shelter beneath rocks. 3 am. A young man wakes up in the core of Kathmandu, walks out of his two-storied brick house with a bucket and struts towards Dharahara, piercing through the thick, all-engulfing fog. There, he walks down the stairs that leads to the golden water spouts for his morning bath. When done, he returns to his house with a bucketful of water to boil and serve tea to his customers for the day.

Thus began the daily routine of Kathmandu’s first tea seller, Tilauri Maila. He had picked up the term of endearment because of the tilauri—an elongated confectionary prepared with sesame seeds and molasses—he sold at his store in Dharahara. Others knew him as Dharahara Maila. But his real name was Bekha Narayan Dangol; a name unknown even to those who frequented his shop for many years of their lives.

And in the 1940s to well into the late 1970s, many did visit this shop, and it remains etched in the memories of a generation of Kathmandu residents now into their 70s as the place where they drank their first ever cups of tea. Various authors and chroniclers have also recounted Maila’s shop in several articles and books.

The man himself, however, remains shrouded in intrigue, much like his shop. But if tea today has become an inseparable part of Kathmandu’s life and culture, Tilauri Maila, and his brother Jog Narayan Dangol, better known as Kanchha Dai, are individuals whose stories are begging to be told.

It is worth mentioning that tea was not the first thing that these brothers sold from their rented store. In fact, their shop existed long before the brothers started selling tea.

That Bekha Narayan was known by the name Tilauri Maila itself speaks to the popularity the tilauri they sold had acquired. Tilauri was what the shop started with, by Bekh Narayan’s parents, with the eatery’s menu gradually expanding to include vegetable curry, aloo chop, sweets, nimkin, jeri, and roti that were served on fresh saal leaves.

According to living family members, the brothers and their families woke up well before dawn because these dishes they served needed ample prep-time. Then as the dim light filled the sky, the shop’s surroundings slowly stirred. To its east lay Sundhara whose spouts uninterruptedly gushed crystal clear water.

The sound of the flowing water blended with those of local women, men, children, taking baths, washing, filling water jars as they started off their day. The ancient Newar settlements lay cloistered in Khichapokhari to the west, and towards Sankata and New Road to the north. Further ahead in the east, Tundikhel spread like a long, green mat from Ranipokhari to Tripureshwor. And beyond the Baghdurbar, located south of Dharahara, the space sprawled open and wide all the way up to the ghat on the banks of Bagmati in Tripureshwor.

When precisely this famous little tea-stall rose to speck this vast open space isn’t documented, and many of those who visited it in their youth today seem to have different opinions.

“Must be between 1954-57 CE,” cultural expert Satyamohan Joshi, 99, says. Around 1957-58, reminisces singer Premdhowj Pradhan, 80, in an article he was quoted in 2013. “Father would take me to the shop when I was a child,” says Shridhar Lal Manandhar, 79-year-old veteran photographer,

born and raised near Dharahara. “Must have existed before 1944.”

Even Tilauri Maila and Kanchha Dai’s families are incognisant of the finer details. But Bidhya Man Singh, 60, Kanchha Dai’s son, asserts that the shop existed long before the 1934 earthquake, even though its famous tea found its way into the menu only much later. This original shop, Bidhya Man says, was located in Khichapokhari, while the shop that many remember today is the relocated one situated south east of Dharahara, in the building that houses Dharahara Dental Pvt Ltd today.

Luckily, a record exists to assert that the shop existed by the early 1940s in the latest, supporting its claim as perhaps the first tea shop of Kathmandu.

In the mid-1940s, Kanchha Dai started visiting the famed sage Shivapuri Baba who divided his time between his ashrams at the top of Shivapuri hill and Dhurvasthali, the forest east of Pashupatinath. When about three decades later, a pediatric, YB Shrestha Malla, started recording conversations between the Shivapuri Baba and his devotees, Kanchha Dai was one of the persons he interviewed. Shrestha later compiled the interviews into the book Right Living: The Teaching of Shri Shivapuri Baba.

“It was in the year 1945 when Gore Dai took me to SB [Shivapuri Baba],” says Kanchha Dai in the book. “I had then a small tea-stall serving tea, and some cookies like Nimkin, Tilauri, sodawater and some fruit.”

Although its actual date of opening remains unknown, what is clear is that when the shop first opened, tea was still mostly unknown to Kathmandu’s taste buds. At the time, the day usually began with a tamakhu for the smokers, or a pyala of aila for some others, according to other accounts.

Tea was known to only a few in Kathmandu—the Ranas who studied in India returned with tea packets and soldiers who fought in the Second World War also returned with their palates introduced to tea. To others though, tea was a drink that evoked a feeling of astonishment. The late novelist Diamond Shumsher Rana had recalled when he was 92, in an article by Jaydev Bhattarai in the monthly magazine Yubamanch, that he would be struck with awe when the then PM Chandra Shumsher’s sons Daman Shumsher, Khem Shumsher and Som Shumsher, who studied in Allahabad, India, said “Chiya piune chiya” (Let’s drink tea) and started sipping from their cups.

Now, from their shop, Tilauri Maila and Kanchha Dai introduced this “astonishing” drink to Kathmandu’s common folks.

The tea was complementary in the beginning. And this coloured, sweet drink continued to astonish customers in its initial days. Bidhya Man recalls his father recounting that some customers found the process of using tea leaves to bring colour and then discarding it, instead of eating it, very amusing.

“Why do you only serve us the soup?” he recalls his father recollecting some customers saying. “Don’t you plan to serve us the fleshy portion as well?” Some said in earnest, while others in jest.

With time, customers themselves began asking for tea, and the brothers started charging small price. Gradually, Tilauri Maila and Kanchha Dai’s shop became a popular teashop and eatery.

Yet how did the two brothers, enterprising as they were, come across the idea of selling what was an alien drink to Kathmandu’s residents? According to Tilauri Maila’s son, Rinendra Man Singh, 74, the two most likely acquired a taste for the drink and learned how to prepare it while on a pilgrimage to India.

Once back from pilgrimage with package of tea leaves in tow, the two eventually began experimenting with the beverage at their store, offering customers what would have been their first taste of tea. Bhairab Risal, 90, Nepal’s foremost environmental journalist, says that he drank tea for the first time around 1948 in the shop. Premdhowj Pradhan has reminisced about frequenting the shop in the 2013 article. Diamond Shumsher Rana also said in the Yubamanch article that it was here that he first drank tea.

With time, the shop’s reputation flourished due to its uniquely prepared tea. At first the brothers employed the commonly used method of boiling water and milk together with tea and sugar. Later, says Bidhya Man, they adopted a unique method of boiling black tea and milk separately. They’d be mixed in a tumbler along with teaspoon of sugar just before serving.

Also remarkable was the size of the glass the tea was served in. Rinendra Man says it was served in a glass tumbler that was double the size of tea glasses commonly used today. Tea itself, he adds, could be ordered either half glass or full glass.

Although tea was only an addition to the shop’s already popular delicacies of tilauri and aloo chop, the special tea became its identity.

“Slowly, several tea stalls sprung in Kathmandu,” YB Shrestha Malla says, “But Tilauri Maila’s was certainly the most popular.”

And it was the tea, according to Malla, that made the shop a popular hub in Kathmandu, a place teeming with activity right from the break of dawn. Many stopped at the stall after their routine early morning bath in Sundhara. Students from Durbar school swarmed about in the afternoon. Then, as dusk fell, army personnel stopped over as they returned from parades at Tundikhel.

These gatherings, Malla adds, were unusual. This is because it was during the point in the Rana Regime when political awareness and activism was on the rise, as was repression against it by the Regime. Any platform that saw large congregations of people quickly fell under the state’s surveillance.

Although it did not garner the reputation of Laptan Ko Hotel, the tea shop in Dillibazar opened in the late 1940s, as a noted point gathering of freedom fighters during the Rana Regime and during the Panchayat era, Tilauri Maila’s stall was certainly under the Rana scanner. In fact, the regime kept such a watchful eye on Laptan Ko Hotel that BP Koirala avoided the place altogether. In disguise, he cycled from his hideout in ‘Living Martyr’ Ramhari Sharma’s home in New Baneshwor and silently drank tea in Maila’s shop, says writer and political commentator Arbind Rimal in his book 1997 Dekhi 2017 Saal: Ek Awalokan.

It’s not known if Maila or Kanchha Dai actually knew that BP visited their shop. Nevertheless, they must have served him with pride, as they did to all their customers. In fact, Maila’s very act of selling tea was itself revolutionary, says Diamond Shumsher Rana in the Yubamanch article. It would come in his tone when he talked about it, he is quoted as saying.

Yet we cannot say with certainty if the brothers understood that they were, albeit unintentionally, introducing a drink that would become inseparable part of the daily Kathmandu routine. Indeed, very little is actually known about these men and their personalities, especially Tilauri Maila who died young at the age of 55 in 1966. Thereon, the stall continued to expand in terms of the variety of dishes it served, even as more tea stalls or hotels opened in the ensuing decades.

According to family sources, the stall eventually shuttered its gates forever in 1979. By this time, it was decades since tea had become an inseparable part of Kathmandu’s (and Nepal’s) culture. But by then, this tiny shop, rising like a speck in the vast openness of Dharahara, had left an indelible cultural mark, evident in, among others, the strong memories it left in a generation of Kathmandu’s residents.

17.56°C Kathmandu

17.56°C Kathmandu