Miscellaneous

The lives of others

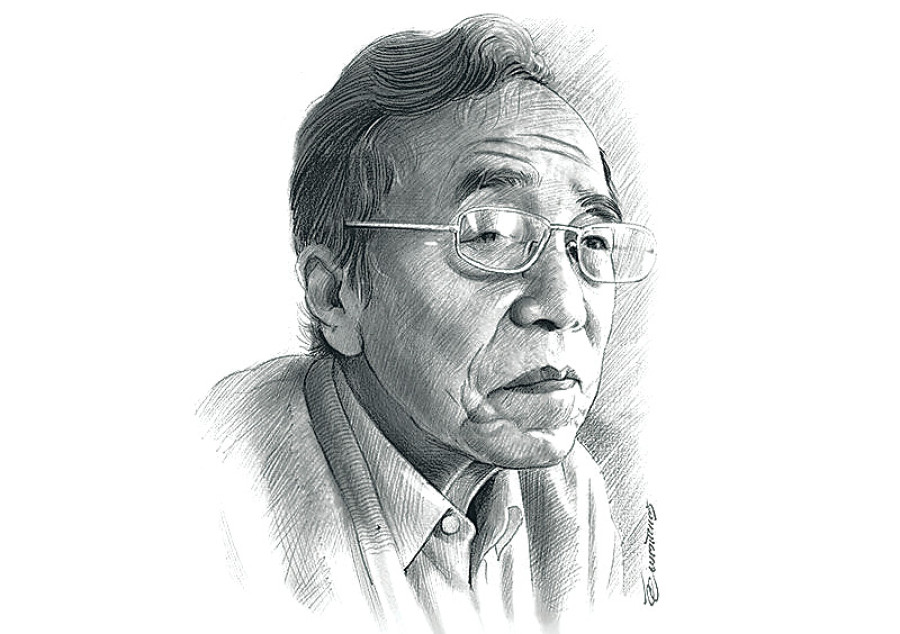

The iconic Nepali writer from Darjeeling, Indra Bahadur Rai, passed away at the age of 91 a few days ago. He leaves behind an enormous literary legacy encompassing both fiction and non-fiction.

Shradha Ghale

The iconic Nepali writer from Darjeeling, Indra Bahadur Rai, passed away at the age of 91 a few days ago. He leaves behind an enormous literary legacy encompassing both fiction and non-fiction. We are fortunate that some of his finest works have now been translated into English. A few months after the publication of There’s a Carnival Today, Manjushree Thapa’s translation of his novel Aaja Ramita Chha, Prawin Adhikari has come out with a new translation of IB Rai’s short stories.

Collected under the title Long Night of Storm, these stories demonstrate the scope of IB Rai’s vision; they deal with large-scale events such as war, exile and migration as adeptly as they explore the ordinary and the mundane.

The movement of people and their complex relationship with the land of their origin is a recurring theme in these stories. In ‘Mountains and Rivers,’ people migrate across the border to escape the relentless hardship of life in the hills of Nepal: ‘Happiness arrived unannounced sometimes perhaps during the festivals; otherwise life was the constant negotiation with a string of worries and fears.’ In “Jaar: A Real Story,” one of the best in the collection, a pair of lovers—a Magar woman and a Gurung man—leave their village in east Nepal and head towards “the land of the Mughals” after they become outcasts in their community.

‘The Long March Out of Burma’ recounts the harrowing journey of a Gurkha family fleeing the Japanese advance during the Second World War. Each of these stories is firmly rooted in history and explores questions of identity and belonging even as it gauges the depth of individual suffering.

The most compelling stories reveal what’s essential about the character in few words, and through carefully selected details. One such story is titled ‘Thulkanchi’. Thulkanchi is a poor niece who lives with Rambabu’s family, though she could very well be a servant girl towards whom Rambabu feels masterly kindness.

We know neither her place of origin nor the town or time period in which the story is taking place. And yet the characters’ smallest words and gestures reveal all we need to know about Thulkanchi. She is a little girl who yearns to be loved despite being aware of her position in the household. She craves Rambabu’s affection but his sweet and empty words fail to convince her. One day, after he scolds her, she runs off to the woods and hides in a hollow.

“Let them think I have gone away.” Her heart ballooned with happiness. She felt loved. Now she recalled how she had carefully hidden her tin box of possessions under the stack of firewood, and now she laughed as she imagined the look of astonishment on their faces. “They’ll think I have run away with my clothes and my box.” Once more, she felt wanted, and felt joy.

The story reveals IB Rai’s astounding ability to inhabit the consciousness of his characters. Under his astute and tender gaze, a simple story of a hurt child hiding in a hollow becomes wrenching and unforgettable.

The title story ‘Long Night of Storm’ begins with a vivid image of kerosene-can sheets nailed to a roof rattling “khaltaang-khaltaang khat-khat.” (The translator has wisely retained such onomatopoeic words throughout the collection.) A violent storm rages all night, and Kaley and his parents fear a landslide might swallow them and their house. We feel the palpable terror and helplessness of their situation.

The story allows us to experience the vulnerability of people who live their lives barely shielded against the elements. Should they live in cramped quarters in the bazaar and toil for wages or should they live off their own land and face the constant threat of being swept away? The characters in the story battle with the perennial question that still confronts a large section of humanity.

Most of these stories present deprivation and longing as an integral part of the human condition. In ‘A Pocketful of Cashews’ we see a man walking home with some cashews for his sick child. He has never eaten cashews and is tempted to try them. But he must save them for his son, so he eats them in his imagination. “He tasted it on his teeth, at the base of the tongue…His teeth were coated with the cream of ground cashew; the base of the tongue was plastered with the thick, white cream.

The mouth sensed the nuttiness of roasted cashews.” The image powerfully reproduces the taste and texture of cashews, and in doing so, reveals something fundamental about this man: He is someone who is daily forced to suppress even his humblest desires.

The great master of the short story Anton Chekhov once advised his brother: “The main thing is to avoid the personal element. Your play won’t be worth a thing if all of its characters resemble you…People should be shown people, not your own self.” Rarely are IB Rai’s characters disguised versions of the author.

Unlike some writers whose best works emerge from an unflinching examination of the self, IB Rai focuses his gaze outward and draws his stories from the lives of others. Also like Chekhov’s, his stories seem rooted in the principle that the job of the writer is not to provide answers but to ask the right questions.

He neither takes an explicit moral position on his characters nor passes clear-cut judgments on society and politics. His stories often leave the reader pondering about the ambiguities of life.

Beautifully translated into English by Prawin Adhikari, these stories are now available to a wider readership. Certain stories in the collection seem more amenable to translation than others. Occasionally I came across awkward sentences that could possibly have been rephrased without distorting the meaning of the original— eg, “Damp clothes had been torn to ribbons by the foliage;” “…broad, gleaming veins pulsed thickly with love and kindness and hatred”;or the translation of kalo fateko talo as “a black rag riddled with holes” instead of “a torn black rag.” I also noticed a few typos and some phrases with strange syntax, such as “cholera ran slaughter through the camp,” “Ajay scolded aside his mother,” etc. It was unclear whether these were deliberate choices or oversight.

Like all good fiction, the stories in this collection can be enjoyed without any knowledge of the context in which they were produced. Still, interested readers might have benefited from a brief introduction or a translator’s note explaining, say, why he changed the story titles or how he selected the stories. I wished at least the year of publication had been provided at the end of each story.

But these are minor flaws given the daunting, almost impossible, task of literary translation.

Vladimir Nabokov describes three sins of literary translation in his essay ‘The Art of Translation’.

The first sin involves mistakes made “due to ignorance or misguided knowledge” and is hence forgivable. The second, a much graver sin, is committed by the translator who deliberately avoids what he either doesn’t understand or thinks his readers will find obscure or inappropriate. The third and the worst sin is committed by “the slick translator” who bends, “with professional elegance,” the original work to a shape that conforms to “the notions and prejudices of a given public.”

Adhikari is guilty of none of these sins. He has given us a responsible and meticulous translation that stays as true to the original as possible, and for this we owe him our appreciation and gratitude.

16.92°C Kathmandu

16.92°C Kathmandu