Miscellaneous

A Press for the Masses

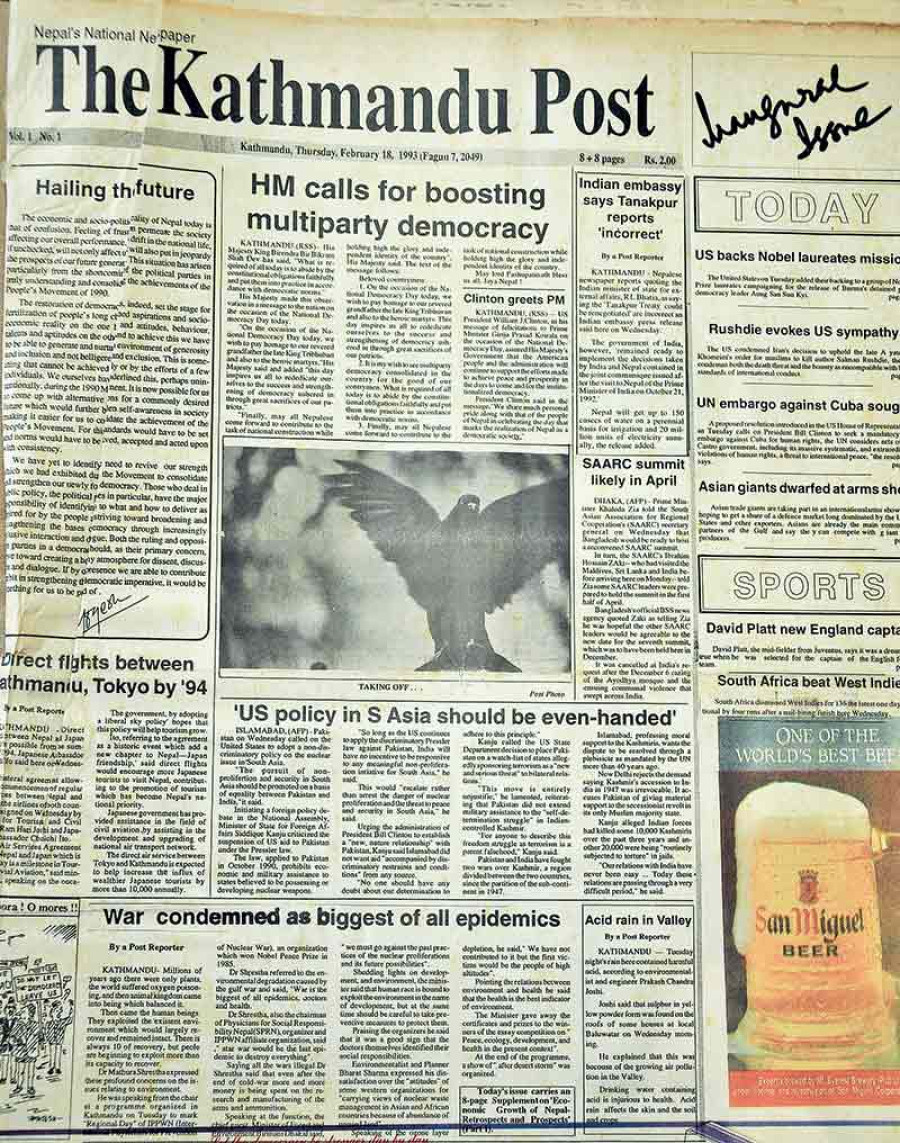

Today The Kathmandu Post and Kantipur, Nepal’s first private sector broadsheet newspapers, complete 25 years of publication. Born after the 1990 People’s Movement, we have been nurtured well by open political space, a growing and curious middle class and the urban centres that have sprung up across the country—thanks to the ever-expanding highways and motor roads.

Today The Kathmandu Post and Kantipur, Nepal’s first private sector broadsheet newspapers, complete 25 years of publication. Born after the 1990 People’s Movement, we have been nurtured well by open political space, a growing and curious middle class and the urban centres that have sprung up across the country—thanks to the ever-expanding highways and motor roads.

Today The Kathmandu Post and Kantipur, Nepal’s first private sector broadsheet newspapers, complete 25 years of publication. Born after the 1990 People’s Movement, we have been nurtured well by open political space, a growing and curious middle class and the urban centres that have sprung up across the country—thanks to the ever-expanding highways and motor roads.

Unsurprisingly, I am asked all the time by foreign visitors why our newspaper circulations continue to grow, at a time when theirs have seen a sharp slump, or even closures, due to the onslaught of free online content and social media. There are two primary factors that have contributed to this: growing literacy rates and new settlements along roads and highways. One of the first things that open in these new towns are stationery shops and book stores, and newspapers quickly become one of their first trading commodities. The papers attract curious readers, a vast number of them young, and that helps their overall businesses, too.

In an open society, people also discuss the content, often disagreeing strongly to what they see in the papers. Available almost across the country, Nepal’s newspapers, in all forms and sizes, have greatly contributed to the marketplace of ideas. It all started with the new democratic constitution, promulgated in 1990, which guaranteed press freedom: “No news item, article or any other reading material will be censored.” (Article 13: Press and Publication Right).

Twenty-five years ago when we started out, Nepal’s literacy rate stood at 40 per cent. Today almost all our children go to school and live within 30 minutes from their school. In the 1970s, we had a total road network of 2,700 kilometers; today it stretches over 80,000 kilometers, littered by a vast number of towns that weren’t there ten years ago.

When our editorial team sat together last month to write about 25 years of The Kathmandu Post and Kantipur Publications, we decided that the best way to tell our story was to discuss the post-1990 democratic evolution itself. It wasn’t possible to cover all major events and sectors, given both our time and resource constraints. We therefore picked up 25 representative individuals and 25 major events from the democratic period. We then solicited eight articles from social scientists, a human rights activist and a literary writer. We are well aware that we could have covered a larger ground and selected a mix of writers who would better reflect the diversity of opinion and depth of knowledge-base available in our society now.

Pratyoush Onta, an academic researcher, explains how this period has seen a huge upsurge in production of academic journals; Pokhara’s Prithvi Narayan Campus (PNC) alone produces more than 25. And the journal production is just not concentrated in Kathmandu, the obvious academic hub, but has also spread all over the country—to Ilam Bazaar, Bhadrapur, Dharan, Biratnagar, Birgunj, Bharatpur, Baglung, Nepalgunj, Surkhet and other locations. Onta argues that the constitutional guarantee of democracy with fundamental rights with respect to the right to organize and the right to freedom of expression has primarily contributed to the rise of researches being undertaken and in turn academic journals being published and read.

Ajaya Dixit, a hydrologist, offers a detailed account on our energy debate: where and why we went wrong and if our new rulers have the moral and political obligation to deliver a samriddha Nepal, now that the elections to the three tiers of government are complete and the new governments, in Kathmandu and in provincial capitals, have taken office.

He offers some hard facts: 25 per cent of our population still lives without access to electricity and our annual per capita electricity consumption, at 132 kWh, is the lowest in South Asia. Our efforts at hydropower development in the past 25 years have helped in overcoming some aspects of generation bottleneck, the author argues, but have not contributed in overcoming major demand side barriers, or elevated people’s economic and social wellbeing.

Deepak Thapa, our columnist and a social scientist, explains how the idea of inclusion got mainstreamed in our political discourse. While the federal project hasn’t gone entirely according to what the marginalized groups desired, it would be quite safe to say that the Nepal of today is politically a much more inclusive state than any time in the past, according to him. The quest for inclusion, he says, has a long history, with most of the groups now identified as being historically marginalized—women, Dalits, Janajatis, Madhesis and Muslims—having engaged in sporadic action since the middle of the 20th century for greater acceptance of a dignified space within the nation.

In the same vein, Mohna Ansari, a member to the National Human Rights Commission, argues how for all the debates and discussions on the new constitution, the document hailed as a watershed moment for a ‘New Nepal,’ could not do justice to the Nepali woman.While celebrating the democratic evolution, scholar Ajaya Bhadra Khanal who has closely studied our political parties, worries about how corruption and “insidious factors” are weakening the parties. As the Nepali state devolves from the top-down, and from the Centre to the periphery, political parties have begun to play a much more central role in Nepal’s democracy. Political leaders in Nepal, he believes, have also refused to accept the transition from “the rule of man to a rule of law,” resulting in “frustrating instances of abuses of power, nepotism, corruption and impunity.”

As the country transitions into the federal setup, editor and publisher, Kanak Mani Dixit, emphasizes that the “Nepali civil society that was shaped by Panchayat- era ethos must develop clarity and courage on the path to implementing the new Constitution.”

If one had hoped that the younger members of academia/civil society—particularly scions of the Panchyat-era elites—would stand for demoracy, human rights and pluralism, that expectations was rudely belied, he says.

Aditya Adhikari, the author of The Bullet and the Ballot Box: The Story of Nepal’s Maoist Revolution, writes about how the Maoists today are caught between “an unviable utopianism and a mere survivalism” and how the party needs to look for ideas in sources that lie beyond the Maoist canon if it is to contribute to the regeneration of Nepal’s political culture and institutions. He believes that Biplav today is in the same route that Prachanda was earlier.

Manjushree Thapa, a novelist who recently translated IB Rai’s seminal work Aaja Ramita Chha, contrasts the spoken Nepali language with written Nepali—which is “formal, requiring rigorous study.” Because the diction of written Nepali is high, with many words rooted in Sanskrit, she observes, many ordinary Nepalis struggle to understand Nepal’s newspapers and official documents.

There is also an important attempt, within Nepali-language literature, to wrest the language away from its ‘high,’ or formal, written form, and to write in the ‘low,’ or informal, spoken form, she writes. “Writers from the earlier generation (such as Khagendra Sangraula) did this deliberately by writing in vernacular dialect in certain works (such as Junkiriko Sangeet, where the characters speak in a particular Dalit dialect from the mid-hills).”

Wise and erudite, Manjushree has a word of advice for the Nepali media, as we mark our 25th year: “As the Kantipur Media Group celebrates its twenty-fifth anniversary, perhaps its editors, reporters, analysts and columnists can look towards contemporary Nepali literature for examples of more inclusive and democratic forms of expression.”

My own journey as a journalist started in April 1990 at the height of the People’s Movement. It would therefore be fair to say that I’m a baby of the post-1990 period, a time marked by new openness that allowed free flow of information and ideas, as press freedom was guaranteed by the constitution. Twenty-five years since we started our humble journey, Nepal’s media landscape looks far more robust. We would like to think that our papers, Kantipur and The Kathmandu Post, have made our share of contribution to this important democratic exercise. This 25th Anniversary edition is a small addition to that giant leap.

Akhilesh Upadhyay

Editor-in-Chief

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu