Miscellaneous

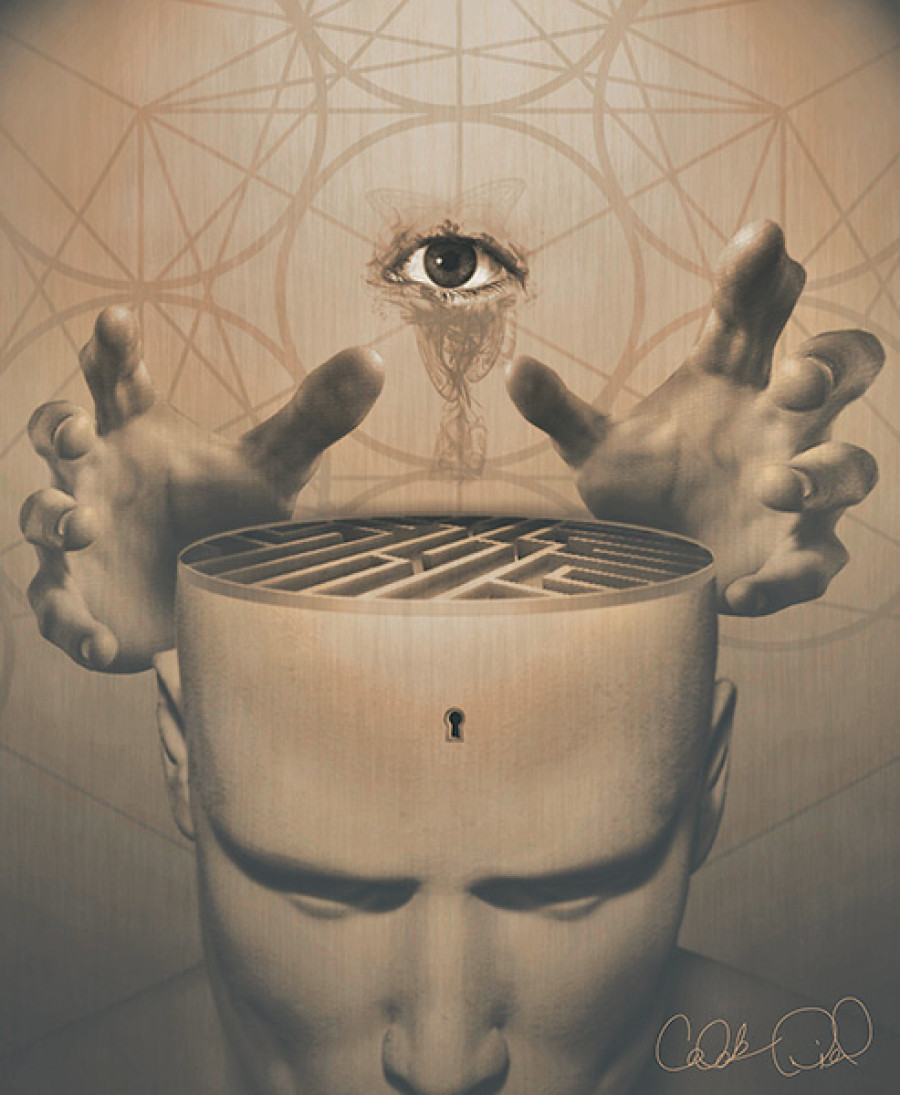

Inner workings

Change, as the adage goes, is the only thing that is constant. Throughout human history, changes—big and small—have altered the way we live, the way we identify ourselves and the arbitrary lines that we have created to demark what is ours and what is not.

Subodh Khanal

Change, as the adage goes, is the only thing that is constant. Throughout human history, changes—big and small—have altered the way we live, the way we identify ourselves and the arbitrary lines that we have created to demark what is ours and what is not. Often, momentous revolutions, usurp the old order and usher in a new one that promises prosperity to all, if not an outright utopia altogether. Yet, the fact that only a select few reap tangible benefits from the overhaul is no secret. A majority of the people just silently watch revolutions come and go, with neither prosperity nor progress trickling down to them. They quietly go about their lives, consumed by their own mental preoccupations, even as the larger world around them crumbles and is built anew. This motif has been explored and extrapolated on by several authors throughout history, and perhaps none better than the prolific Anton Chekhov. Living in a time when Russia was making a difficult, oftentimes violent, transition from feudalism to socialism, Chekhov’s short stories are not about the ‘great’ revolution that was taking seed but rather turn their gaze towards those that are left-out, the ones untouched by both the old orders and the new.

Critic and writer Mahesh Paudyal, in latest book, has attempted to replicate the Chekhovian formula in a Nepali setting. His story collection, Tyaspachhi Phulena Godavari, captures a timeframe of a decade and a half of our recent past. A time when Nepal saw some of the biggest transitions of its political and social history. Paudyal has, however, steered clear of politics, and has instead stuck to the tales of the individuals who have been left behind, even as momentous changes swept the nation.

By and large psychological and tragic, Paudyal’s stories depict marginal and socially-othered characters like the elderly, a lonely, schizophrenic woman; the poor and the hapless; and children who have been grossly misunderstood by adults. In a society that doesn’t understand, these characters suffer untold miseries. They struggle to survive, and finally resign altogether. Few characters recuperate from their conditions and are rehabilitated back to life. But even in doing so, the author seems to be ruminating on changes that have neither uplifted the nation as a whole, nor have they led to individual joy or satisfaction. The general mood in the past few decades in Nepal has been one of frustration, and this perennial national exasperation has found voice in Tyaspachhi Phulena Godavari.

Altogether twenty in number, Paudyal’s stories are ‘inside stories’ of his characters’ psyche. The book begins with the story titled Nursery in which a father, bereaved by his infant son’s recent demise, finds solace in embracing another child—a stranger’s son. When caught between his duty as an administrator and his feelings as a father, he decides to quit the job to be with the child. Exploring the psychology of ‘lack and fulfilment’, which runs the risk of social misinterpretation, the story sets the tone for a book that seeks to delve into the mind of the ‘common’ citizen largely indifferent to the monumental changes afoot in the country. Another story, Nidal, centres on the inner world of an old man, in which he stands robust as long as the house he built stands tall, and falls, when the house is dismantled. Deeply symbolic, Nidal, the main beam of the house, stands for a person’s personal empire, which is a source of their pride and satisfaction. Another episode, Hulaki, narrates the story of a postman, who was once celebrated and somewhat famous while the postal services remained in wide use, but is reduced to nothing when the service whittles after the onset of quicker technology. The Hulaki, in the story, finally quits his thirty-year-old job as a postman, and recedes into obscurity. Based in the hinterlands of Ilam, the story explicates the changing relationship between postmen and villagers, which now has become all but non-existent.

One of the dominant intrigue of Paudyal’s fiction is his treatment of children. Though the stories are decidedly for the adult audience, he has continued to cite children as subjects of conflict and injustice, and has pleaded in favour of their safety. The story Adalat Bahira features two children, whose childish marriage-game becomes the cause for parental conflict. The parents end up going to court over the matter, where after a daylong hearing, the case is dismissed because the judge himself is thrown down the vistas of years, when he himself used to play marriage-games with his childhood girl playmates. Sikari is a story of a rebellious boy, Siddhartha’s struggle, against his grandfather’s attempt to nurture masculine characters in him. Naturally rather soft, Siddhartha is again and again exposed to violent scenes, like castrating of goats, animal-sacrifices at shrines, and killing of a male deer. Finally, he slings mud at his grandfather and disappears from the scene. Krantiveer too is centred on a twelve-year-old boy, who throws stones at the king who rapes his mother. By hinting at possible sources of revolt, Paudyal has demonstrated that causes of big revolutions might be big or small, and sometimes even trivial.

Paudyal’s women are not empowering, strong characters. Instead they are lonely and sidelined. The protagonist of Drishyantar is a schizophrenic woman, who receives slights and blows on roadsides on a daily basis. On the night of the Tihar, she fi

nds a pretext to dance and purge all her subdued emotions. She dances and dances, until she collapses to the ground. But come the next day, she is thrown back to the same routine again. By showing time as a static entity, Paudyal seems to question the claims of oft-lauded social transformation.

The title story Tyaspachhi Phulena Godavari features a combatant, Pungin, who is in an all-cleansing war against another tribe. He sneaks into the narrator’s household for a hide-out and shares the story of killing a mother and her daughter with a single blow of his sword at the pressure of his commander, against his own desire to save the two. The author has, through the symbol of chrysanthemum argued, that a symbol, if it reminds of an inhuman characteristic, is worth forgetting, no matter how beautiful it naturally is.

Thus, by bringing to life an array of drift-off characters, Paudyal has unravelled a neglected fragment of our society, without whose development all claims of national development will remain bogus. Paudyal may, however, face the criticism of collecting too many stories in a single anthology. All his characters are weak and forlorn, and they do not send forth any ray of hope. The author seems lopsided in his viewpoint, because his tales do not reflect the positive sides of the changing Nepali society.

So, all in all, Tyaspacchi Phulena Godavari is a pleasant read that will leave you pausing between the pages. Paudyal’s characters might not be your traditional heroes that stay with you long after you’ve read the book, but that is exactly what the author is trying to highlight—the forgotten.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu