Miscellaneous

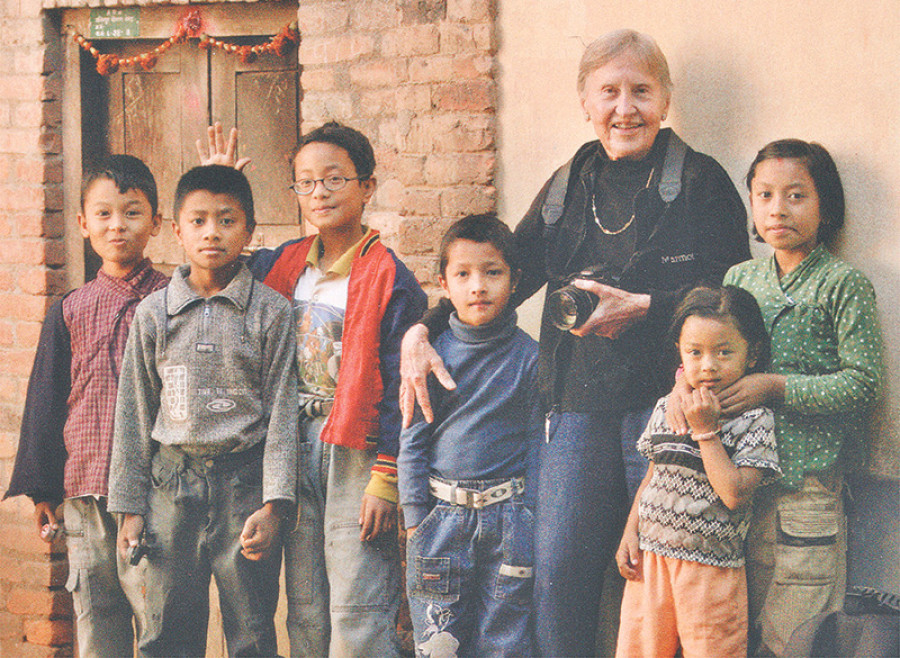

A personal tribute to Mary Slusser (1918 – 2017)

We lost a prominent Kathmandu icon during the earthquake of 2015: Kasthamandap, the storied building which was then thought to be about a thousand years old, but is now believed to have existed many centuries earlier in some form.

Dipesh Risal

We lost a prominent Kathmandu icon during the earthquake of 2015: Kasthamandap, the storied building which was then thought to be about a thousand years old, but is now believed to have existed many centuries earlier in some form. Now we have lost another Kathmandu icon, Dr Mary Slusser, who has done so much in her long career as an art historian, anthropologist and archaeologist to introduce Kathmandu’s Newa art and culture to the world.

It was during the initial burst of activity to salvage the ruins of Kasthamandap after the earthquake that I tried to get in touch with Mary Slusser, who had written extensively about Kasthamandap. Apart from introductions, I asked for permission to reuse the Kasthamandap elevation and plan drawings funded by her research and drawn by Wolfgang Korn.

This inquiry was quickly followed by Mary’s response, which set the tone of our friendship and introduced me to the personal, human side of a scholar responsible for such monumental works of Nepali cultural studies as Nepal Mandala and The Antiquity of Nepalese Wood Carving:

“Of course you may use the drawing or anything else you need. I have been very, very concerned about Kasthamandap because all the powers interested in restoration of the monuments are fixated only on the royal squares whereas Kasthamandap historically is far more important. I have said that the ruins should be carefully searched to be sure any and all elements, such as the capitals of the four central pillars, and especially any copperplate inscriptions [are located and saved.] I am truly sick at heart about what nature has wrought in the region I admire and love so much, as do you. Please keep in touch?”

What became clear in the subsequent interactions and collaborations between us was the deep passion she maintained for Nepal, even decades after having left Kathmandu. Specifically for the website that I maintain (rebuildkasthamandap.com), she reinforced, again and again, the importance of Kasthamandap as the very epicenter of Kathmandu culture. Kasthamandap was Kathmandu, and vice versa. For an article published in ECS Nepal, she had this to say about Kasthamandap:

Kasthamandap is Nepal’s heritage defined, a witness to its history and evolution as a nation for almost a thousand years—and likely more. No other traditional building in Nepal could compete in size, antiquity or cultural impact. It must not be allowed to perish.

But Mary Slusser had always loved Kathmandu. That much is clear from the level of dedication she put into her research, starting way back when, as the spouse of a US diplomat in Nepal, and armed with a PhD in South American archaeology from Columbia University, she wrote a series of articles for the AWON Bulletin from around 1965 to 1971. This was later published as Kathmandu, a typed/ lithographed compendium.The writing style was one of an amateur enthusiast, rather than of the powerhouse of cultural knowledge she was soon going to be: no doubt this was in part due to the nature of her audience, since these articles were intended primarily for the expat community in Kathmandu. But her enthusiasm for the subject matter comes across loud and clear even in these early writings, as is evident in her treatment of the curious fish of Asan Tol:

The fish of Asan Tol is a small stone relief carved in a shallow, rectangular stone basin now embedded in the macadam street where the unheeding traffic of the busy square rolls over it. Although none [i.e., no scholar] can say who actually placed the curious image here, for what reason or when, the people of the quarter tell a tale of it and include it in their daily round of worship. Like the washya dya, or toothache god, of Bangemudha Tol, it is one of the many divine specialists consulted for aid in curing specific diseases and ailments of the body, with vertigo as its special field of concern.

The fish of Asan Tol, so goes its origin tale, commemorates a strange happening in which a son was teacher to his father. For, once upon a time there lived in Kathmandu a renowned astrologer named Barami……

What followed in subsequent years was a series of rigorously researched publications, first in academic journals, then in two books which have together become indispensable to studying the rich Newa culture of Kathmandu. First, in the two-volume 1982 magnum opus Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Nepal Valley, she masterfully weaved the story of the valley using the twin threads of “Hindu” and Buddhist heritage, pulling in the ancient colorful strands of the ajimas, matrikas, pitha devatas, serpents, and daemons constituting the original often aniconic, occasionally chthonic deities of Kathmandu Valley, while underlying the entire woven quilt with the deeply embedded South Asian notion of Royalty which has permeated Kathmandu culture from the Licchavis through to the Mallas and the Shahs.

This excerpt from Nepal Mandala about the Kumari cult showcases her in true form:

To my knowledge, the Licchavi records are silent about Kumari worship. However, the late chronicles assert that Sivadeva I (A.D. 590-604) placed Four Kumaris at the crossroads of “Naubali” or “Navatol” (Deopatan) when he established the city, and that Vasudeva, an undocumented successor, placed “Kumari Gana and Naudurga” near Jayavagisvari…

That much has been recorded in Kathmandu’s Vamshavalis since medieval times, and known to the world since 1877 CE with the publication of an English translation. Where Mary can go further, as she does, is in tying this together with her personal knowledge to strengthen the hypothesis that, perhaps, the Kumari cult originated in the fifth-sixth century, rather than in the twelfth century during the reign of Laxmikamadeva as is more widely believed.

…Considering that there is, in fact, a very ancient Matrika shrine attached to Jayavagisvari temple, itself unquestionably a Licchavi foundation, the chronicles may be correct, and reveal a previously unimagined antiquity for the Kumari institution in Nepal Mandala.

In her second book The Antiquity of Nepalese Wood Carving (2010), Mary published stunning revelations about the tunaa’s (struts) of Medieval Kathmandu buildings. Specifically (among similar findings), Mary was able to confirm via radio-carbon dating that he following ethereal Salabhanjika (One who breaks the branch of a Sal tree) gracing one of the figural strut of Uku Baha (Rudravarna Mahavihar) was created between 690-890 AD: ie, possibly more than 1300 years ago. That the Salabhanjika still shows off the individual strands and curls of her hair, the patterns of her thinly veiling sari, the jewelry on her head, and the details of the foliage above her, are testament to the master craftsman who created her, as was commented on by Mary herself in the book.

Mary’s contributions are not limited to her own published research. She played an important role in ensuring that the works of Nepali academics were disseminated and recognised worldwide. She did benefit immensely in her early days from the research output of the (now much-maligned, but important) Itihas Samshodhan Mandal associated with Naya Raj Pant and (in the early days) Dhanavajra Vajracharya: that much is clear from the many references to the work of this traditional “institute” in Mary’s publications. However, she more than repaid her debt. If not for her, the rigorously researched body of work from the Samshodhan Mandal might have largely gone unnoticed except among Nepali academics and the few International experts fluent in Nepali and/or Sanskrit. Mary also collaborated and published jointly with Dr Gautamvajra Vajracharya, Dhanavajra’s nephew and scholar extraordinaire who still writes prolifically about Nepali culture. It was in fact, Mary who put Vajracharya in touch with Pratapaditya Pal, which resulted in the young Vajracharya obtaining a position at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

When Nepal Mandala was first published, some scholars criticised her for making sweeping generalisations, for loosely shifting between anthropology and art history, and for not communicating anything new in terms of the interplay between Hindu and Buddhist traditions in the Newa civilisation of Kathmandu. But when it came out, Nepal Mandala was such a monumental work, so ambitious in its goal, so sweeping in its scope, so vast in having woven together art, culture, history and religion and so inclusive of the ancient motifs of Kathmandu culture (such as Ajimas, Dakinis, daemons, ghosts, etc), that to find fault with it is to nit-pick. Certainly successive generations of scholars, literally following in her footsteps, have unearthed and modified various cultural and historic aspects of what Mary first presented, but this is a natural process in any field of study. Mary was the pioneer who told the complex, layered story of Kathmandu culture first. To this day, Nepal Mandala stands as a stupendously rich and deep assessment of the Kathmandu Valley culture: I can think of no later to me that can match its scope and detail. Now that Mary is no more, I think it is high time for Nepal to recognise her contributions in an official manner.

So thank you, Mary, for inspiring me to delve deep into the culture and history of Nepal. Thank you for making me fall in love with Kathmandu all over again. And finally, thank you for being my unofficial Guru Aama. Nepal will forever remember you for the light you shone on its rich culture and heritage.

- A version of this article, which includes a complete bibliography of Mary Slusser, is available at rebuildkasthamandap.com

10.21°C Kathmandu

10.21°C Kathmandu