Miscellaneous

Remember, remember

“The myth is the public dream and the dream is the private myth. If your private myth, your dream, happens to coincide with that of the society, you are in good accord with your group. If it isn’t, you’ve got an adventure in the dark forest ahead of you.”

Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga

“The myth is the public dream and the dream is the private myth. If your private myth, your dream, happens to coincide with that of the society, you are in good accord with your group. If it isn’t, you’ve got an adventure in the dark forest ahead of you.”

—Joseph Campbell,

The Power of Myth with Bill Moyes

.................................................

Next week will bring up two years since the Gorkha Earthquake. In the disaster’s aftermath, Nepal’s ‘resilience’ quickly became a buzz word and we—at least those of us passive in our urban lull—quickly moved on. There were jobs to get to, bills to be paid, and a fuel shortage to worry about; and soon, just like the aftershocks, the vulnerability that we lived through receded into memory.

Yet, those days and weeks following the earthquakes were a strange time to be alive. Fear was all pervasive, the uncertainty debilitating, and we as families, communities and a society huddled together, trying to explain a calamity that even in this modern day and age remains elusive and unpredictable. Many turned to science, hounding the internet for websites that made lofty claims of using cutting-edge devices and algorithms to predict when the next “big” one would come rattling our doors. Many others sought otherworldly answers: Was the Bungyo dyo, in procession from Bungamati to Patan, not honoured in the right way? Did the Dolakha Bhimsen sweat during the year, portending a calamity? What did the Google Boy say?

But we often forget that Kathmandu is no stranger to earthquakes. Before the 2015 quakes gave us a sobering lesson on impermanence, we all at some point pestered older relatives about the 1934 earthquake. Then there have been others—stronger, more violent—peppered through the millennia of recorded history of the Valley. The first one of those was recorded in 1255 AD—purported to have been 7.8 on the Richter scale—which had its epicentre very close if not in the Valley itself, and wrought widespread damage; by some accounts, up to one third of Nepa Valley’s residents perished in the quake—an untold tragedy, when put into perspective.

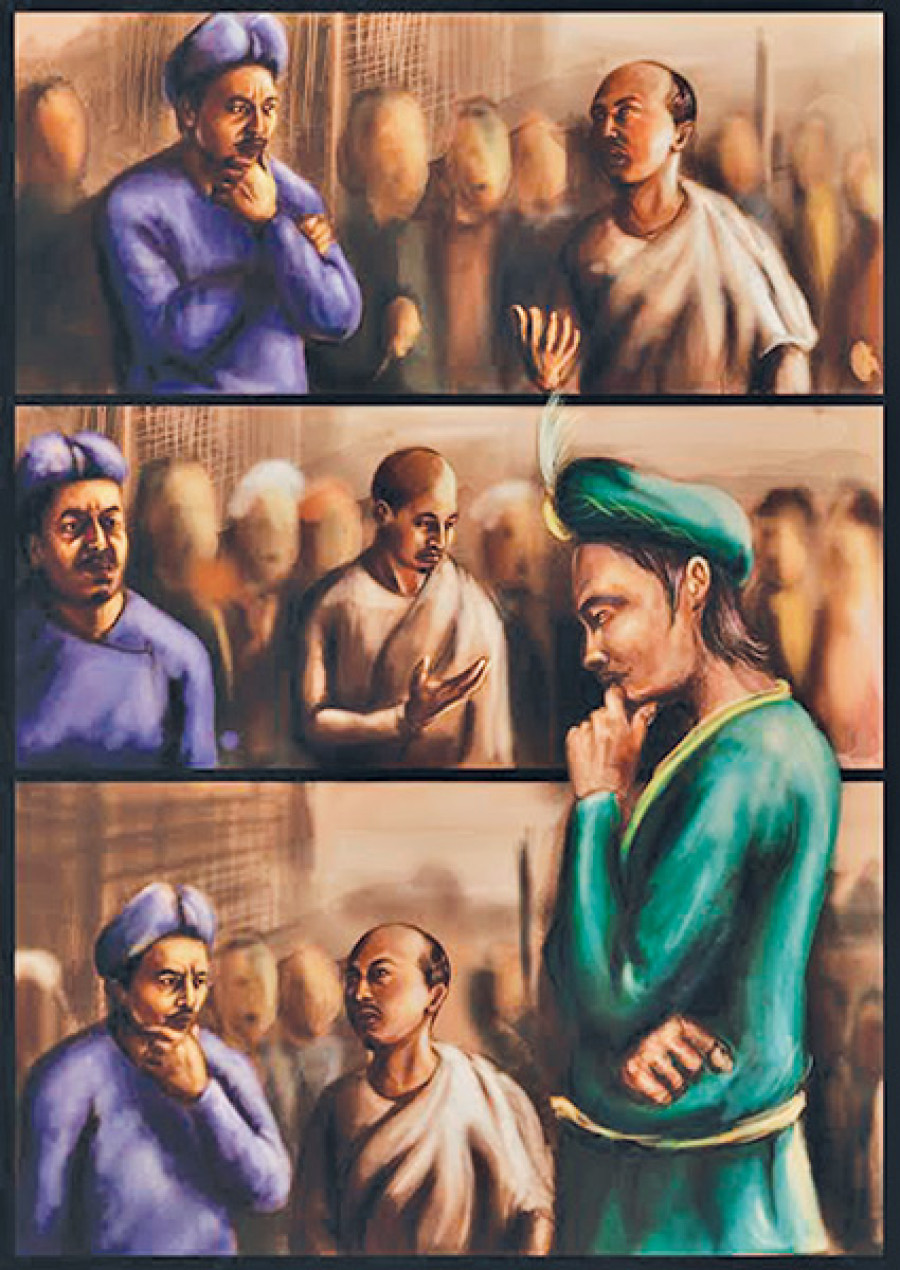

If we, so called modern residents of the Valley, were so easily bated by hacks or the superstitious, how did our forbearers seek to answer questions that are not-so-easily answered? What god’s wrath did they attribute the destruction of earthquakes to? How did they respond as a society in the aftermath? These are some of the questions author Rishi Amatya and illustrator Prakash Ranjit seek delve into in their newly-released graphic novel, Lumanka Ti. Set in 1254 AD Bhaktapur, during the reign of Ananda Malla, the novel tells a fictionalised history that re-imagines the events, both political and supernatural, that surrounded that devastating quake of yore. And in doing so, the duo has not only undertaken the task of patching together an intriguing portrayal of history but also furthering a genre of storytelling that remains in its infancy in Nepal.

Those who grew up in the 80s and 90s will fondly remember the craze over western comics like Tin Tin, Asterix and Obelix and Archies or Indian staples like Nagraj, Super Commando Dhurba and Parmanu. But comics, much less graphic novels, never really took off in Nepal. In recent years, there have been the odd publications, most notably the Ms Moti series by Kripa Joshi, but by and large, the graphic novel, and even comics for that matter, remains a medium of storytelling seldom explored in Nepali publishing.

Which is why, Lumanka Ti is at once trailblazing as it is engrossingly fresh. Interweaving historical facts, mythologies and imaginations into a compelling narrative that keeps the pages turning, the graphic novel boldly walks into unchartered waters and blurs the line between recorded history and ‘phantasy’—without doing disservice to either. As Amatya himself puts it in the author’s note, “All of these [myths] rattled my mind as much as the aftershocks, as I wove the narrative. I heavily borrowed and took creative liberties with stories and myths going as far back as the 7th Century, and as early as the early 18th century. While doing so, I have chosen to eliminate a lot of historical and cultural references…Anymore and it would have been a textbook and not a graphic novel.”

What emerges then is a unique piece of literature and art that is a short, gripping cover-to-cover read that still leaves much for the discerning reader to interpret between the lines. But what is most fascinating about the graphic novel is its appeal to a wide range of readers—in the few short days that I have had Lumanka Ti at home, it has been wolfed down by my 90-year-old grandmother and my eight-year-old cousin, and everyone in between; leaving each with takeaways unique to what they themselves brought to the book.

All in all, Lumanka Ti is a labour of love (which took two painstaking years to bring to fruition) that undoubtedly will be palatable to those of varied tastes. And barring the few typos and an occasionally confusing storyboard, it is a novel that you should be able to read and reread in one short sitting.Envisioned as a three-part series, each based in one of the Valley’s three ancient cities, perhaps in the years and decades to come, Lumanka Ti will be remembered either as the graphic novel that finally brought the storytelling medium to the mass Nepali public, or at the very least a flash-in-the-pan that attempted to do so. Either way, it is a book worthy of being a collectible.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu