Miscellaneous

Ground zero: Pattharpuruwa

The pleasures two different forms of art, say a book and a play, elicit are quite different. Reading is a solitary activity.

Timothy Aryal

The pleasures two different forms of art, say a book and a play, elicit are quite different. Reading is a solitary activity. You go with the ebbs and flows of the written words, and the pleasure you draw from it depends upon your own personal imaginations. The same metaphor may invoke one reaction in one reader, while something entirely different in another. While in theatre, the imagination is somewhat shared and hence somewhat constrained. It’s all there on stage to see.

While going about sharing one’s experience about a work of art which itself is based on another work of art, should one compare the two, as one that aspires to reach up to the quality of the original? When an artist bases her work on another, is she unconsciously influenced by the original? Or is the end goal to offer something unique, something that stands apart in its own right?

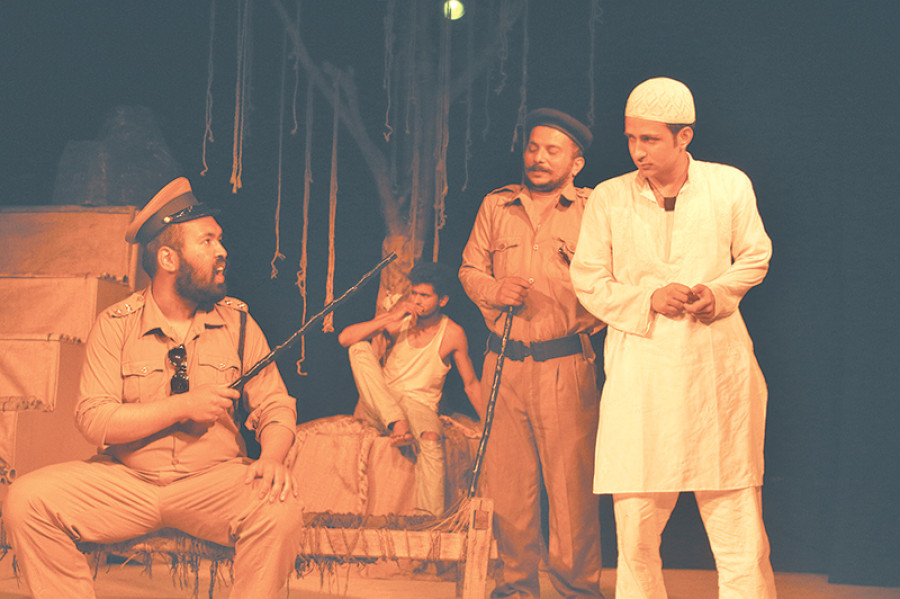

Take the play Loo, for instance. Presented by the Tandav Theatre and directed by Sarita Shah, the play (currently on stage at Mandala Theatre) is based on the novel of the same name by Nayan Raj Pandey. Adapting onto stage a widely-acclaimed book—one that has captured popular imagination as much as any other recent Nepali novel—come with its own risks and challenges. Does the play capture the same essence of the rural Tarai village of Pattharpuruwa as the novel did?

The fictional Pattharpuruwa is an impoverished village bordering India—a village where seemingly absurd events transpire day in and day out. Girls are misbehaved regularly; the perpetrators vanish into thin air. The SSB (Sashastra Seema Bal—India’s border force), dressed in yellow uniform, intrude time and again and show their strength, often resorting to beating locals without any rhyme or reason. A bespectacled Hindu priest, suffering an grotesque physical ailment, trades false ideas in exchange of money. (In one instance, the priest, namely Tute Pandit played by Bivek Tiwari, recommends an alcoholic that drinking his own urine mixed with a right proportion of camphour will help him get him rid of his habit.) Radiolal (played by Anil Kurmi), unable to forget his wife who’s left him, wears her petticoat in response. This is Pattharpuruwa. And there is one problem here that looms larger than anything else: The continuous encroachment by the SSB. During the closing sequence of the play, we find out that the village has been taken over by India.

All of these events transpire so rhythmically and so quickly that it’s jarringly nauseating to see them on stage. But even amid this seemingly chaotic chain of events, the denizens of Pattharpuruwa seem content with life as is, embracing all of it with humour and warmth.

Execution of all this, however, is mediocre at best. The producers have brought characters who actually speak the regional dialect, and don’t have to fake it, adding the play an extra layer of authenticity. In the highlight performance of the show, Milan Di Capri, as Ilaiya, delivers an understated and powerful performance (Anil Kurmi as Radiolal and Dipeeka Dhakal as Chameli seem natural too), while other actors are inconsistent, struggling to rise above mere caricature.

Moreover, the play mixes deadpan one-liners (in one instance, a character says something like this: “To love a woman is like keeping Colgate into your mouth; it’s only sweet only for some time”), that send fits of laughter through the audience. The sets designed to portray the Pachhuwa Chiya Pasal, where the villagers meet to have talks over tea, stays unchangeably throughout, even when the actions are clearly taking place somewhere else.

The play Loo tries to mirror a marginalised rural society at its most basic; it does evoke all the many absurdities, and tragedies that transpire in a society. But given the inconsistent cast, it leaves plenty of space where you’d wonder if only some of the characters were as natural as others.

Although it’s amusing more often than not to witness all the absurdities that Loo offers on stage, the play itself is bereft of a central pivot that strings together all the action. Is it trying to make a statement about the political wrangling between Nepal and India, and how those citizens living in the margins have fallen prey to it? One can only guess, given the lack of the play’s convincing assessment. And like the central character, Ilaiya, our irascible hero with a tragic flaw, who falls one-sidedly in love with Nushrat (played by Aarjoo Kharel) only to lose her ultimately, the same flaw plagues the play.

12.72°C Kathmandu

12.72°C Kathmandu