Miscellaneous

Artists and their cities

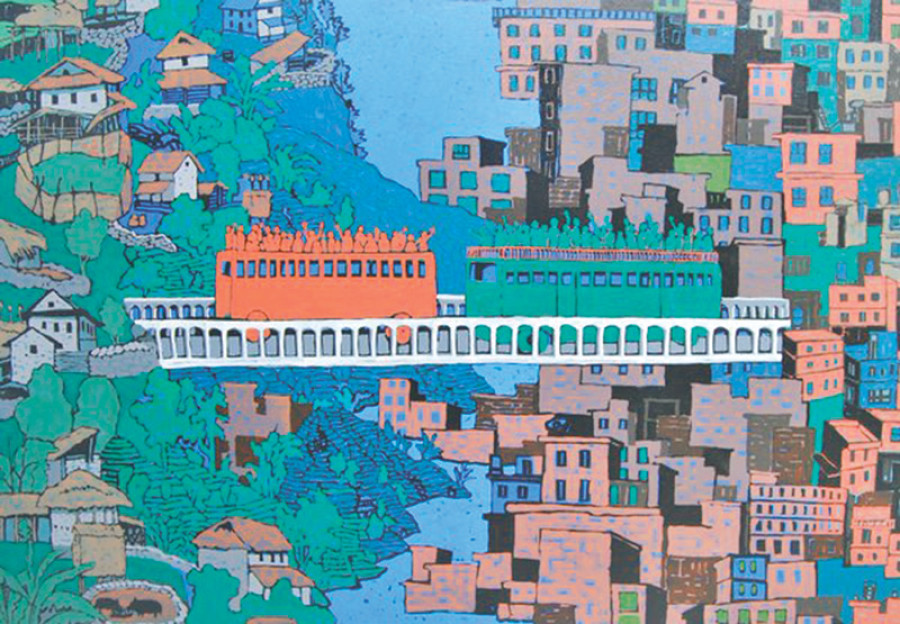

The day after returning from Egypt, I listened to a curator speak about cities. The masterclass was part of Kathmandu Triennale, an international arts festival, scheduled to open in the spring.

Niranjan Kunwar

The day after returning from Egypt, I listened to a curator speak about cities. The masterclass was part of Kathmandu Triennale, an international arts festival, scheduled to open in the spring. Since the festival theme is “The city, my studio; the city, my life”, the curator referred to artists who had unique ideas about their lives in cities. At one point, he mentioned, “Artists should offer visions that are not getting offered elsewhere. Cities provide materials—clay, paint, stones. But before that comes context”. A volley of questions followed—How am I living in my city? How do I respond to it? What does the city make me do? Say? Think?

My thoughts were soaked in Egyptian hue. Once, in twilight, a motorboat had taken me across the Nile river. By the time a jeep transported me to the low-lying western desert hills, the autumn sun was high in the sky and the rocky caramel terrain shimmered. This was a site where numerous royal mummies were discovered over the centuries. This was a necropolis, the city of the dead. Enchanted, I gingerly stepped into King Ramsis’ cavernous underground tomb, dug over three millennia ago. Its sandstone ceiling and walls were covered with illustrations and symbols, replete with various shades of green, blue and red, with colours extracted from minerals and plants. These depictions, carved by skilled artisans, were meant to guide the spirit during its potentially perilous journey through the underworld.

During the masterclass, I quietly marvelled at an emerging theme connected to these two disparate projects—how artists, moulded by their environment, leave enduring marks. How an environment, an era, a dense metropolitan concentration of lives, how our vast, infinitely diverse emotional, mental and bodily states give birth to ideas and trends.

The ancient Egyptians lived in an era before Jesus and before Allah. They believed in the supreme creator, the sun god Atum-Ra who was swallowed every evening by Nut, the deity of the sky. This creation myth permeated every aspect of their lives. The ruling pharaoh was a son of Atum-Ra who could overcome death. Just like the setting sun went inside Nut, only to emerge the next day, a spirit also travelled through the underworld and came to life again once it received permission from Atum-Ra.

Evidence and relics suggest that the ancient Egyptians had a profound belief in this spirit world. The Great Pyramid was King Khufu’s tomb; its slopes represented sunrays that helped the spirit’s ascension. As ideas evolved, subsequent rulers were buried under pyramid-like desert hills. Over time, this network of numerous tombs created a subterranean necropolis. Each tomb—whose size depended on the length and impact of a pharaoh’s rule—contained a mummy surrounded by statuettes and amulets of deities and animals, all of whom could be brought to life in the underworld and called on to aid the spirit. Also included were everyday items such as chariots and chairs, furniture and food, jewellery and jugs.

Elaborate death rituals—for example, a high priest mummified a body wearing a mask of Anubis, the god of the afterlife—were performed, recorded in hieroglyphics, and later compiled into the Book of the Dead. Bodies were preserved so that the spirit, upon returning, could identify its form. During mummification, which took 70 days, dead pharaohs were soaked in mysterious mixtures, their brains extracted through the nose, and vital organs removed through a slit on the left side of the abdomen. These organs were preserved separately inside canopic jars, made out of wood or stone. The lid of each jar was sculpted to represent the protector of organs: Imsety, the human-headed god, looked after the liver; Hapy, baboon-headed, guarded the lungs; jackal-headed Duamutef looked after the stomach and falcon-headed Qebehsenuef guarded the intestines.

While the west bank of Nile was a place for the dead, the east bank was home to the living and their deities. Grand temples, dedicated to Atum-Ra and Nut, rose up to meet the sky. More than 3,000 years later, the only remnants from the ancient Egyptian civilisation are pieces of their temples and tombs that are intrinsically tied to their cult of creation and cult of death. Archaeologists are still studying these artworks and investigating the details of a highly sophisticated empire that survived for almost 4,000 years, a phenomenon unlike anything that has occurred on earth before.

A few days after the masterclass, I found a sunny spot inside a Pulchowk cafe where I waited for Karan Shrestha, one of many artists participating in the Triennale. Since he split his time between Kathmandu and Mumbai, Karan’s invitation to meet had pleasantly surprised me.

“You see—Kathmandu, since it’s surrounded by hills, doesn’t have a horizon,” Karan started talking, after settling on a couch across from me. Looking at a face washed with sincere gravity, I listened, eager to hear his thoughts on our city.

He said something to this effect—When there is no horizon, there is no sense of going outwards. So there’s stagnation. It’s almost like the city is spinning on itself.

“I’m using the geography to inform the psychology,” he explained, releasing a half-smile and pausing to look at me. “That’s my conceptual framework for the Triennale project... But I want to get multiple viewpoints. What do you think? What are your thoughts on Kathmandu?”

Ironically, the question made me think of another city, a city of skyscrapers, glowing at the other end of the world. I had fallen in love with that city before I genuinely got acquainted with Kathmandu. I had left my hometown when I was a wide-eyed teenager and returned with a broken heart. That was the truth.

Karan’s question required a response, which I provided, silently—You say the hills constrain. But some of us, somehow, grew up looking outward, over the hills. When I was a young boy, I longed to see the horizon. I longed to see a round orange sun sinking into the ocean. Kathmandu was dark. It was dirty. It was a city without possibilities. It didn’t have space for me.

Soon after returning, I was introduced to a British writer who was in romance with this alien city, the way I once was with my foreign love.

This man was writing an account of Kathmandu’s art and politics, its history and society. He had left his western world of possibilities and settled in our city.

There were others. There were Austrians and Scots, Germans and Belgians who called Kathmandu their home. Our journeys between the east and the west had been opposite. Perhaps, just like the ancients, they believed that the east is meant for new beginnings and the west signifies a long rest. Perhaps I had been wrong all along. So I started looking closely. I looked beyond the brick and concrete. I ignored the dust.

All kinds of people called Kathmandu home. I met artists who were envisioning novelty. They were busy creating, getting hands dirty with wet clay, urgently demonstrating structures and shapes never seen before. Sometimes they chased beauty, sometimes change.

Once I listened to a group discussing the socio-political dimensions of art. Arjun Khaling was one of them. He had recently moved to a place where art intersected with politics. He was looking at life from this vantage point.

These interactions revealed strands of light illuminating old, dusty corners. After all, it was possible. After all, we are restless. After all, life is dynamic. Elements will enter and exit. The city will always be in flux. These movements, these departures and returns, are inevitable, undeniable. Leaving was as important as arriving.

That late autumn afternoon, long after saying goodbye to Karan, I was still in communion with him—To live in a city, to love it, one must leave. One must walk away and rise above.

I was talking to no one and to everyone—Stand on higher ground and gaze below at the spread of human grime blanketed in smog. Pretend to be better off. Lock yourself in a small foreign room and imagine the wild monsoon thundering through warm summer days. Imagine the rains sweeping through ancient alleys, polishing green leaves once again. Know that the dying city regularly resurrects itself.

What do I think of Kathmandu? This is not a city of my childhood or a city of my nightmares.

How do I respond to Kathmandu? There used to be a cluster of trees over there. Now it’s all steel and concrete.

What about its people? Well, an artist died in mid-December. Arjun Khaling killed himself at the end of another year. His body was found hanging from a ceiling hook, tethered to a muffler, on a sunny winter afternoon. Refusing to witness a new beginning, choosing death over creation, he wrote a note, taking full responsibility, blaming no one.

His body was buried close to temples and trees in central Kathmandu according to Kirat rituals.

Kunwar is an Assistant Editor of La.lit magazine; he also works as an educational consultant

13.3°C Kathmandu

13.3°C Kathmandu