Miscellaneous

In our own lives

It’s strange to have seen this person nearly every day of my life and to have no idea what his voice sounds like

Prateebha Tuladhar

He walked past me yesterday morning. We looked at each other. We always do. That’s the only thing we’ve done for each other in the last 30 or so years. I don’t have an account of the timeline. But that’s all we’ve done.

Yesterday, I noticed he was dressed in mourning. Cream-coloured shorts, tee, slippers and a cap over shaved head—the muted tones indicated loss. Not that he looked particularly sad. In fact, I’ve thought he has always looked kind of serious. Sometimes I’ve wondered if it had something to do with his name. A name that places you nowhere. I wonder how he feels about that. I’ve hated my own name for as long as I can remember, so I pay a lot of attention to other people’s names. I wonder if he ever took that up with his parents, the way I always crib to my parents about mine. It’s too banal—the way my name sounds. I’ve tried to repeat the vowelsounds in it for an alliterative impact. But it doesn’t do much for it.

Maybe it was his father who gave him his name and maybe he’s emotional about it. I haven’t seen the old man for a while now. He was always there at their Restaurant and Bar—sporting a moustache that was black even when all he had on his head was a wisp of gray.We used to wait for our school bus just across the road. The fatherwas always busy talking toother shop owners. I think they talked politics, mostly, because I do remember hearing terms like Kangres, Emaley, Maubadi in their conversations.

As the years went by, the father looked haggard and withdrawn—probably getting high on his own concoction. I wonder if that affected their father-son relation. Parents and children seem to have complicated relations all the time now. It seems almost fashionable to be that way. I recall this one time when the father was yelling at him, as we stood there waiting for the bus to arrive. He just looked away and left, I think, a little embarrassed thatMohana had seen him. We all knew they were crushing on one another. She left him some a bar of Kitkaton his counter once. I don’t know what happened after, because my memory seems to fail me.

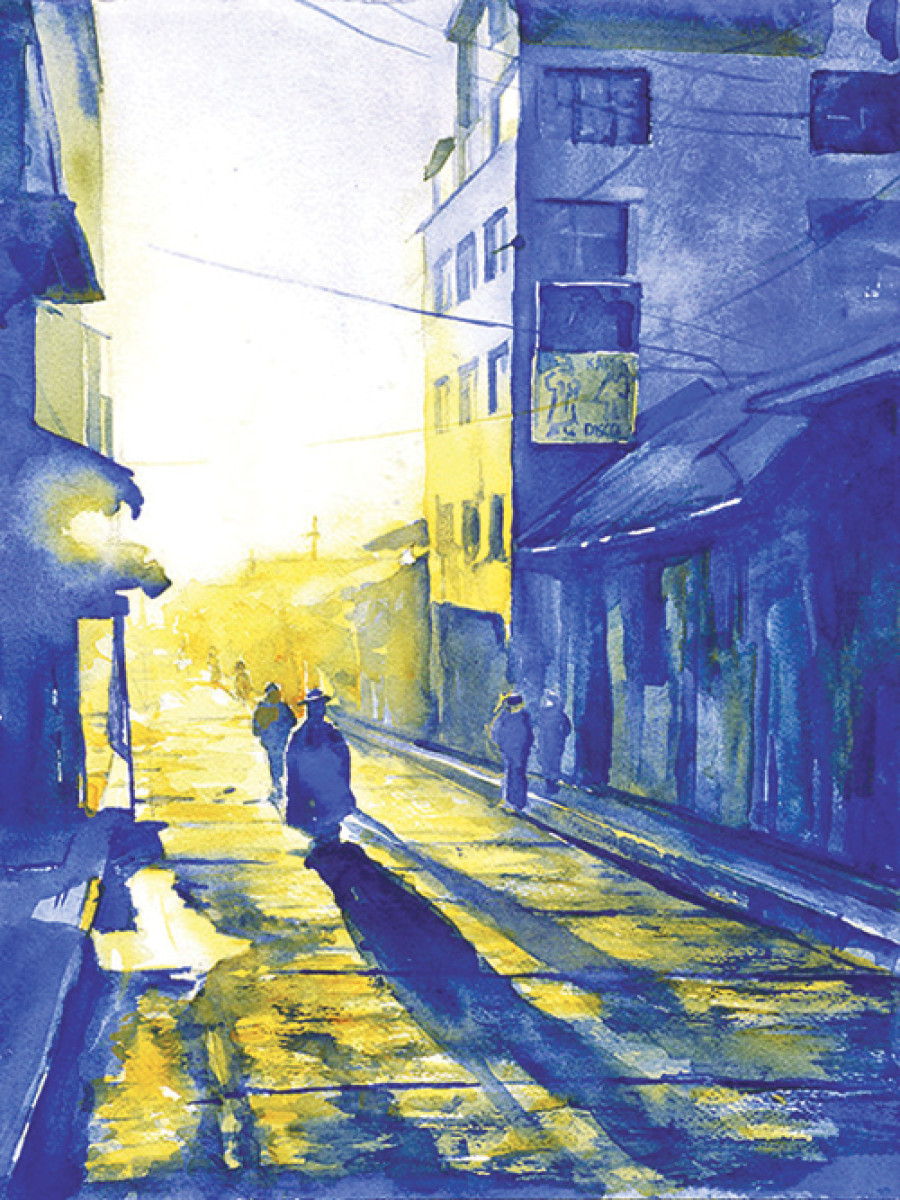

There were times when I ran into him on the little alleyway that provided a shortcut to Ring Road and escape for those who wanted a brief respite from the busy streets. The physical proximity provided by the narrow space of the galli prompted an intention to say hello. But he seemed to wear a wall around him, so I always resisted. I did talk to all the other guys in our neighbourhood when we used to be teenagers—even tothose who just sat outside tea shops in groups playing video games and guessing at the colour of the lingerie of girls who walked by. But I never saw this one hang out with the tole boys. He was either at the counter, wearing a straight face, or wasn’t. I think the fact that theirs was a place for drinking men instead of teetotalers made a difference. If they had sold tea instead, maybe Mohana and I would have stopped sometimes to have tea and then maybe he would have had a chance to make more friends.

When I returned to Nepal after my university education, we had suddenly become adults. I acknowledged his presence, the way adults do, if ever I ran into him in the galli. I think there was an occasion or two when we half-smiled at one another. We’re neighbours, after all. But our greetings were always almost-smiles, and then we were strangers again. It’s strange to have seen this person nearly every day of my life and to have no idea what his voice sounds like. So many years of not taking any notice.

I suppose time will continue to pass us by as we age and retire and die. I wonder if he will start drinking too, like his father, and if he will grow wisps of gray hair and a black moustache, and run the same restaurant and bar for the rest of his life—sitting behind the counter, giving orders and taking in money and handing out change.I feel like we’re growing old together even in this distance which makes us familiar strangers.

We finished our schooling in the same year. I went to university. This boy didn’t. But our gait and disposition, in their respective ways, speak the same language of worn-out patience with life. We’re friends like that—apart in the things we have in common. Yet, even today, after decades of growing up and growing old in the same neighbourhood, we will glance at each other,away, and then keep walking to our destinations. I think that’s what people in this city are fast turning out to become.Strangers.

19.57°C Kathmandu

19.57°C Kathmandu