Miscellaneous

Teen Tin Matti Tel

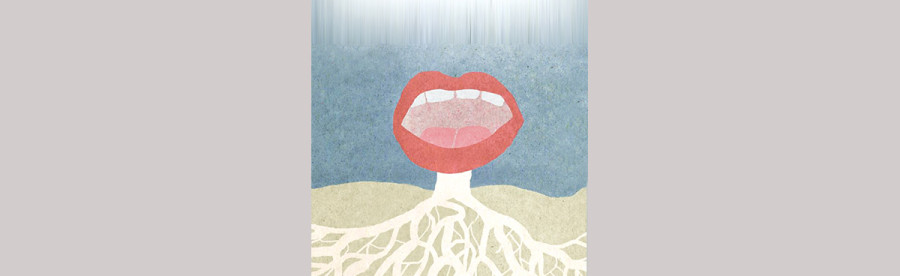

Language is collective memory. It roots a people to a place. Its vowels take the contours of rolling hills, the consonants harsh but malleable like floodplains. It remembers glorious victories and agonising defeats. It rings of thunders and the crackle of droughts.It tugs at an umbilical blurred by the sands of time, all but invisible to the forgetful mind.

Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga

"One does not inhabit a country; one inhabits a language.”

***

I am standing in a serpentine queue at the Department of Transportation Management to apply for a driver’s license. Resolved to go through all the motions in earnest, I ignore a persistent hawker who is offering to fill out the application form for me.

It takes me five minutes to change my mind.

To me, filling out an official document in Nepali is akin to a strenuous academic exercise. An invisible broadcast delay between what I am reading and what I am processing means that I fill these forms with my forehead clenched—concentrating, always forcing.

The hawker looks on expectantly. I take up his offer and we walk to a nearby ‘photocopy’ shop.

In a country like ours, maybe I am lucky to even have a citizenship I can photocopy.

But on a pitiless summer day, standing in a serpentine queue at the Department of Transportation Management, I too feel like an outsider.

A psychological émigré.

***

You would think languages die in the dungeons of a Kathmandu jail on charges of sedition for writing poetry. You would think they are lost under the stranglehold of oppressive nationalism—eroding with time, through a process of persistent muffling and a gradual letting go.

But life is a tad more pedestrian.

I lost my mother tongue on a Monday.

It was in the fourth grade at boarding school. We had just returned to campus from the holidays. Hale-Bopp pierced through the night sky.

A group of friends had approached me, sniggering—their eyes charged with mischief; a new trick they had learned at home rolled up their sleeves.

“Say: Teen Tin Matti Tel,” they asked, too politely.

“Why?”

“Just say it once, na. Teeen Tiiin Maaatti Teel”

“Tin Tin Matti Tyel?”

“What, what, say it once again,”

“Tin Tin Matti Tyel?”

Their laughter echoed to Phulchowki and back. “See, it works every time!”

You would think that languages die in a plume of smoke of burning books, the cancellation of shows on national radio and the shuttering down of newspapers.

But life is so much more pedestrian.

I lost my mother tongue to innocent child’s play, on any given Monday.

***

I am standing at the kitchen sink, eavesdropping on my parents who are submerged in a conversation in their mother tongues.

My parents live fuzzy bi-lingual lives.

They talk about politics in Nepali. They talk family in Newari.

They talk about market prices in Nepali but they discuss the household in Newari.

They talk about their work in Nepali but gossip of co-workers in Newari.

But most of all, when they are discussing something secretive, as they are today, they speak a strain of hushed Newari. You would think they were worried the walls could hear them speak and that the walls spoke Nepali.

In changing times like these, maybe I am fortunate to be at least clutching at straws.

But standing at the kitchen sink, eavesdropping on my parents who are submerged in a conversation in their mother tongues, I too feel uninvited.

Always an earshot away from their most earnest selves.

***

Language is collective memory. It roots a people to a place. Its vowels take the contours of rolling hills, the consonants harsh but malleable like floodplains. It remembers glorious victories and agonising defeats. It rings of thunders and the crackle of droughts.

It tugs at an umbilical blurred by the sands of time, all but invisible to the forgetful mind.

***

I am barely standing at the crowded Kwaacha in Patan, waxing poetic to a patient ‘bartender’.

I speak my most fluent Newari when moonshine is coursing through my brain. And I am either striking a bargain or currying a favour.

In lonely, walled-off times like these, I am trying to get a foot in the door.

But barely standing at the crowded Kwaacha in Patan, waxing poetic to a patient ‘bartender’, we both know I am only pretending.

A cheesy Hindi song blaring in the background has got my wobbly feet tapping, as I slowly count my change in English.

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu