Miscellaneous

Words won’t suffice

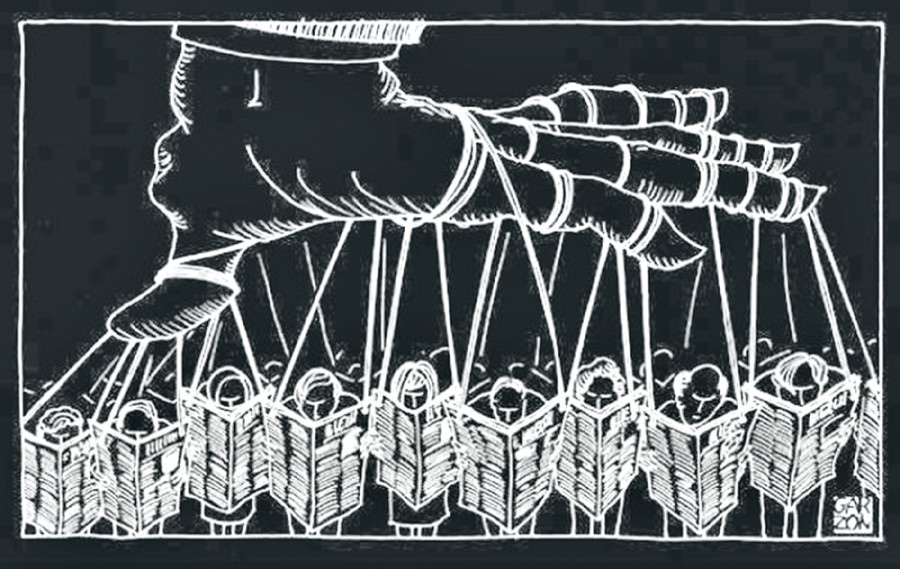

As long as privileges are not equitably and judiciously distributed among all members of society, those at the top will remain where they are

Abhinawa Devkota

With KP Sharma Oli losing support of the Maoists, the game of political musical chair has entered a new session in Kathmandu. In a few weeks’ time, the country is bound to form a new cabinet. But despite the country shuffling its cabinet on a regular basis like one would change one’s outfit to suit the changing season, the presence of representatives from Dalit and various minority groups in leadership positions, in the government and across parties, is conspicuous by its absence.

Active political participation is just one of the many areas where Dalits and minorities are miles behind the rest. Despite tumultuous political changes the country has witnessed in the last few decades, the gates of Singhadurbar and of larger socio-economic progress remain open only for the select few who belong to what columnist CK Lal calls the Permanent Establishment of Nepal (PEON)—a coterie of high-caste, historically advantaged people whose desire to remain in power has forced them to resist changes in society.

This is not to say that social movements to rectify historical injustices against them have not taken place in Nepal so far. But all these efforts have, at best, been carried out half-heartedly, as a gesture, and have not brought about significant progress.

Thus, despite the steps taken by Chandra Sumsher for the abolition of slavery nearly a 100 years ago, the protest by Brahmins in Western Nepal against the use of lower castes to till the land about seven decades ago and, most important of all, the huge public outcry against caste and racial discrimination at different times in recent history that has led to major legal and constitutional reforms, caste and ethnic discrimination is still a major social problem.

The latest social movement in the Tarai, billed as Kshama Yachana Aaviyan, which involves people from higher castes asking for forgiveness from their lower-caste brethrens for all the injustices carried out against them, too, might as well become the newest addition in the long list of failed social movements.

The reason for this failure, as history has shown us, can be located in the unwillingness of the higher caste groups to move beyond rhetoric and tokenism. No doubt, they derive their power from cultural ethos and religious mores that govern our society. But it is the privilege, in the form of material wealth, social clout and opportunities for individual progress, that validates and reaffirms this power imbalance. As long as these privileges are not equitably and judiciously distributed among all members of society, irrespective of caste, class, and religion, those at the top will remain where they are.

Various social reform movements in the region have taken this factor into cognizance. The Brahmo Samaj movement that started in the early 19th century in Bengal had to reimagine a whole new theological terrain of Hinduism, one that completely did away with caste and gender discrimination inherent in the religion, to ensure social and religious equality for all. Despite the perceived prejudices against Dalit progress that Gandhi was said to have harboured, and this has to do primarily with Gandhi’s decision to fast unto death in response to the Poona Pact in 1933 (the pact would have granted the untouchables the right to elect their own leaders), it was Vinoba Bhave, a staunch Gandhian, who started the Bhoodan and Gramdan movements which ensured that hundreds of thousands of poor and landless people, primarily those belonging to the lowest rungs of caste hierarchy and those outside the Hindu varna system, became landowners.

Agreed that India is yet to be expunged of this malice. But this does not go on to prove that these movements became complete failures. Rather, the willingness of the founders and those involved in the movements to include concrete, affirmative action programmes that went on to change the lives of countless individuals shows us the only way the problem can be solved.

Be it the Aaviyan, which now has the backing of more than a handful of Madheshi stalwarts, or any other future reform movement in Nepal, if they are to gain some measure of success they will have to tread this path.

Tula Narayan Shah rolled the dice for the movement when he decided to visit the Dom family of Dev Narayan Marik in a remote village in Saptari to apologise for all the historical injustices committed against Marik and those like him. The challenge now is to keep the momentum going.

When the celebrated Nepali film star Rajesh Hamal was in Siraha last year, the nation got to witness a visceral display of discrimination. A Dom family was barred from using a well in Nayanpur village by some upper-caste people. Later, in the presence of police, they were allowed to draw water, but not before the upper castes decided to stop using that well.

A new well must have been dug in the village in the afternoon of the incident. Because, caste in the subcontinent is not just a religious or a cultural entity. It is also defined by its control over resources, primarily economic. The Doms and Musahars cannot afford to dig a well that Brahmins, Baniyas and Kshatriyas can. As long as this equation does not change, nothing will.

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu