Miscellaneous

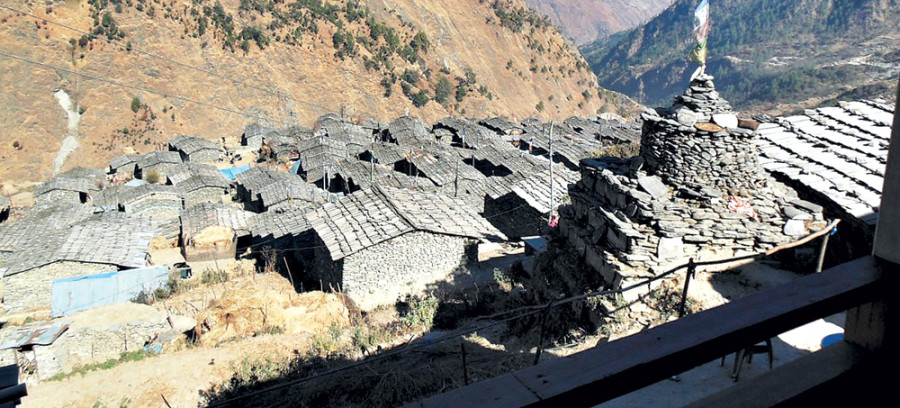

The black roofs of Gatlang

Once lauded as the ‘gem’ of the Tamang Heritage Trail, Gatlang is now scrambling to salvage what the earthquakes ruined

Umesh Pokharel

Phurba Jyalmu has been telling anyone willing to listen that Gatlang, Rasuwa must be rebuilt the way it was. Now that the aftershocks have receded in earnest, the 78-year-old wants her community to stay true to their commitment of using CGI sheet roofs only as a ‘temporary’ solution. “If not,” says Jyalmu, looking at the village now peppered with tarps and zinc roofs, “this is the beginning of the end.”

In the immediate aftermath of last year’s earthquakes, when various agencies and groups arrived at Gatlang, they were surprised to find the residents firmly against the silver-coloured CGI sheets that they had brought with them. “Our village was famous for its black roofs,” says Phurba Singhi Tamang, the coordinator of the Gatlang Rebuilding Committee, “it was an important part of our heritage and identity. Initially, the rejection of CGI sheets was unanimous. But with the monsoon and eventually the winter approaching, we decided to take in the zinc sheets as a very temporary arrangement. We hope to change that once the housing grants start filtering in.”

Prior to the earthquakes, Gatlang, a five-hour hike from Syabrubesi, was a popular stopover for tourists heading into the Langtang region. According to Tsewang Norbu Lama, field programme manager at Umbrella Organisation, a non-profit working to alleviate the impacts of poverty and trafficking in the region, the village was “the gem” of the Tamang Heritage Trail. Gatlang, he says, was lovingly called the “black village” by travellers because of its black wooden roofs and its clustered settlement.

Jyalmu asserts that Gatlang’s black roofs have been a part of its heritage for well over 800 years. Constructed with traditional Tamang sensibilities, the roofs were made of large wooden shingles—sourced from nearby forests—that turned black when weathered by time. The houses themselves had stone walls framed into place by intricately carved wooden pillars—engraved with

traditional symbols and prayers. Most of the houses, says Jyalmu, had engravings of images of the Buddha and lotuses; others had carvings of Tibetan mantras that petitioned for happiness and prosperity.

The prosperity that the village was once awash with is now slowly dissipating, says Pasang Tamang, peering out of her temporary shelter made of CGI sheets. “This is a very new experience for me; all of us have always lived in our traditional houses. It has been over a year since the earthquakes and we have not been able to begin rebuilding the village.” Her biggest fear, she says, is that the future generations will lose a vital connection to their heritage and traditions, should the community fail to rebuild Gatlang the way it was. “Besides, why would travellers continue to come to our village if the one thing that set us apart is lost forever?”

The steady footfall of tourists was a vital source of livelihood for Gatlang’s residents. With the farming output relatively sparse, many of the locals had more recently transformed their homes into cosy home-stays to great effect. A record with the Rural Tourism Promotion Centre-Rasuwa suggests that on average 6,000 tourists visited Gatlang every year prior to the earthquakes. “From a tourism point of view, it is very important for the village to maintain its original setting,” says Tsewang Norbu, “The locals were conscious of the issue when the CGI sheets started coming in. They knew that the tourist footfall would dip if they failed to restore its originality.

It was the only village on the trial that gave an original taste of the Tamang culture with its traditional architecture and lifestyle, in terms of its uniformity and unity.”

Domo Tamang, a local shopkeeper, reiterates how important tourism was to the village. “We used to make good money selling local produce, handicrafts and grocery items to people passing through. The last year has been very rough for all of us. Business has all but disappeared and doesn’t look likely to return if we aren’t able to build the village back they way it was.”

So far, policy provisions, including I/NGO resource mobilisation guidelines and guidelines on grant distribution for reconstruction of private houses damaged by the earthquakes, have not specifically addressed the restoration of houses in traditional ways. “Although Gatlang’s traditional architecture is somewhat similar to one of the prototype designs proposed by the National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), the monetary support the government aims to provide will not be sufficient to construct such houses,” says Manoj Timilsina, a humanitarian worker in the region. The government has made provisions to provide Rs 200,000 to rebuild houses destroyed by the earthquakes, but according to Phurba Singhi’s estimates, the cost of rebuilding one of Gatlang’s houses will run upwards of Rs 1,000,000.

Locals have been lobbying for special consideration with the District Disaster Relief Committee (DDRC) and the NRA, to help preserve Gatlang’s uniquely traditional settlement. But given the wide-spread havoc wrought by the earthquakes on thousands of communities across the country, many locals are fully aware that their pleas will, in all likeliness, go unanswered.

Which is why, with added urgency, the septuagenarian Phurba Jyalmu, is telling everyone that is willing to listen that Gatlang must be rebuilt the way it was. “I lived my whole life building, expanding and maintaining my black-roofed home. I want my grandchildren to be able to understand the value of our traditional houses. They were not just stones stacked together; they were cultural spaces—a lineage passed on from one generation to another,” she says, before pausing to gather her thoughts. “I don’t want to die under this ugly tin roof.”

20.26°C Kathmandu

20.26°C Kathmandu