Miscellaneous

The Gods are still leaving

Despite their theft finding national and international limelight, antiques from Nepal remain vulnerable as ever

In the dead of the night on December 18, the residents of Digu Tole, Thimi, awoke to frantic cries of alarm. Vegetable vendors, on their way to the bazaar, had stopped at the Digu Bhairav for their daily darshan. But the revered statue was nowhere to be found and had been nabbed from the heart of the bustling settlement. As locals gathered and stared at the temple’s vacant inner sanctum, many broke down in grief.

The idol of Digu Bhairav was not a very big one, the face just slightly bigger than a human face. But, to the residents of Digu Tole, it was larger than life. “This idol was priceless, you can never find another one as beautiful,” says Hariman Karmacharya, one of the four priests at the temple. He went on to say that though most idols of Bhairav look angry, the Digu Bhairav had a gentle, smiling expression, which rendered it unique and “most beautiful.” Other residents of Digu Tole added that the idol looked angry if you looked at it with anger, and happy if you looked at it with a smile.

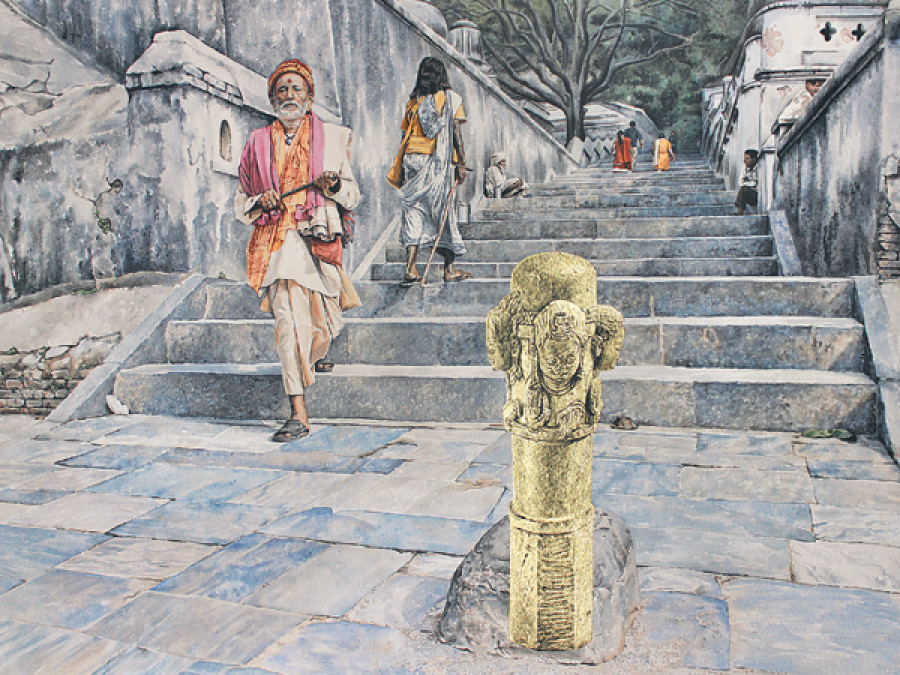

Kathmandu, once called an “open museum” by art historian Jurgen Schick for its abundance of high-quality art in public spaces, is a haven for seekers of such objects, which sell for millions in the right market. In Nepal, while citizens are allowed to own antiques that are passed down in the family, antiques in the public arena are owned by the Department of Archaeology. The Ancient Monument Preservation Act of BS 2013 prohibits, buying, selling, and the “removal” of an antique from its original space. Despite all the restrictions, the theft of antiques peaked in the 1970s and 80s: Schick estimates that over 90 percent of Nepal’s best art left Nepal then. And the pillage of whatever little Nepal has left continues today.

Hiding in plain sight

Antiques are usually stolen from rural, unguarded areas where there is less public scrutiny. An idol, for example, is less likely to be stolen from a temple at Pashupati or Swoyambhu. The idol of Digu Bhairav was one of those not-so-easy to steal, since the temple is located in the midst of a lively residential area. Karmacharya says that there had been six previous attempts to steal the idol, all unsuccessful. On the night of the theft, the area was bustling with activity even until 12 pm. And the theft was discovered at 2 am by vegetable vendors, meaning that the perpetrators had kept a close watch to find a time slot of two hours when it would be safe to steal the idol.

According to Bhesh Narayan Dahal, the Director General of the Department of Archaeology, such incidents have increased after last year’s earthquakes, possibly because of reduced security. “There have been incidents of antiques that were stolen and left lying around, and also of the police intercepting sales and negotiations in the past three months,” says Dahal.

In Nepal, the open border with India means that transporting restricted objects is easy, but antiques also travel through more formal channels like airports or shipments. Even if the transport of antiques is forbidden, “Diplomatic pouches, immune from checking, are frequently used to get around this problem,” said Bishnu Raj Karki, former director general of the Department of Archaeology.

Disguising antiques is another technique. The easiest way to do so is to call it a “curio.” While objects more than a hundred years old are called antiques, a curio is artwork less than a hundred years old: It can be freely transported, bought and sold. Fake paperwork is often created to prove that an antique is less than a hundred years old. “Another way is to pretend that they are imitations of real historical items,” says SSP Sarvendra Khanal, chief of the Crime Department at Metropolitan Police, and imitations have no laws whatsoever restricting them.

Dr Donna Yates, a researcher at the Crime and Justice Center at University of Glasgow, informed that antiques often do not travel a straight path to their destination. They are routed and sometimes re-routed through countries known to have loose regulations. Stolen antiques from the whole of South-east Asia, for example, are gathered and routed through Thailand. Along the way, they gather fake paperwork, making their case stronger as they go.

At the other end, the stolen antiques have a high demand in developed nations—their value growing more than a hundred folds by the time they arrive. Some of these buyers are history aficionados who know the historical value of the object, and many museums fall into this category. There are also many, especially private collectors, who are simply connoisseurs of beauty. “The art speaks to them, they feel like they have to own it, possess it,” says Dr Yates. And imitations are not enough, they have to have the original copy, even if they don’t understand its meaning.

Dr Yates found through her research that museums may not go through the rigorous background checking required to prove that an artwork is not stolen. According to her, despite the fact that the illicit trade by “art dealers” are obvious to a keen observer, police turn a blind eye to their establishments, largely because of the “white collar” nature of the crime—something that happens in the world of the elite without causing visible harm to people. And thus “art dealers” have respectable art galleries of “curios and imitations,” hiding in plain sight of law enforcement. Museums escape scrutiny because they are seen as places of learning, and it seems a sacrilege to associate them with theft.

The long way home

Until even a few years ago, if there was a sale of stolen artwork abroad, it went unnoticed. But with internet, the stolen objects sometimes pop up online. The catalogues of auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s are public, and when stolen artwork is featured, it becomes public knowledge. Many Nepalis have also visited foreign museums where stolen artwork reside. A famous example was the statue of the Uma-Maheshwor from Bhaktapur that the eminent art historian Lain Singh Bangdel spotted at France’s Guimet museum. It was removed from display immediately, and after spending many years gathering dust in the museum’s storage, is being sent back to Nepal this year.

Nepal is a member of Interpol, and that is where we turn to when crime crosses national borders. “We must have two kinds of proof to have such an object returned to us,” says Inspector Surendra Shah of Crime Investigation Department. “Proof that the object is historically important, and proof that the object is ours.”

The road to reparation, however, is not easy.

In the past year, BS 2071-2072, Nepal Police has records of theft of only four antiques. However, according to Dahal, 50-100 items of archaeological importance are stolen every year and may not always come to the notice of the law enforcement authorities. Rabindra Puri, an art conservationist who has been instrumental in bringing back stolen antiques, knows this all too well. He faced immense challenges in 2013 when trying report stolen antiques at an auction at Christie’s. The theft had not been registered, and since Interpol demands registration of theft before beginning proceedings, it was time consuming and full of hassles to get done at the last moment. Besides, objects of historical importance lie at every corner in a historic city like Kathmandu, and not every statue or artwork is documented photographically.

Another challenge is the lack of uniform laws around the world—in every country, the rules regarding antiques are different. For example, in most of Latin America, an individual cannot own an antique. An individual or institution may be granted custody of the object, museums may be allowed to display them, but the ownership always belongs to the government. In such cases, getting the artwork back from government ownership is full of bureaucratic tangles.

In many European countries, on the other hand, citizens are allowed to own, buy and sell historical objects. An object may enter a private collection legally and disappear from public view altogether, making it near-impossible to trace it, let alone bring it back. Also, in most European countries, once the art has entered the country, the work will travel inside the country, be bought and sold, but export permit is simply not issued. Very few countries allow easy transportation of historical objects, and when they do, the rules end up aiding art traders more than conservationists.

Pouring out, tricking back in

The head of a 12th century idol of Saraswati was broken from its body and stolen from Pharping in 1980s. The repatriated head now resides at the national museum in Chhauni while the torso still lies in Pharping, and the disconnect is

painful to watch.

“When you see a piece of art that forms a cultural centre of a community displayed naked in a museum, it just breaks your heart,” says Puri, who is currently busy preparing for a museum housing replicas of stolen art. The theft of antiques from a country like Nepal, he says, are more than just simple theft of historical art. Ours is not a dead civilisation like the Incan or the Mayan, our art and antiques are still alive—a part of living, breathing heritage. Many of the statues and wall paintings stolen are still being worshipped by devotees every day.

It is very clear when you talk to the residents of Digu Tole that Digu Bhairav is one of those idols with deep ties in the community. Chanakeshari Shrestha, who holds the Digu Bhairav as her family deity, shares that all the major ceremonies of her community, including marriages and initiations, are celebrated in front of the temple. It was a place where everyone in the community, whether young or old, went to for darshan every day and drew their strength from. Karmacharya also adds that Digu Bhairav is an important part of Bhaktapur’s Bisket Jatra.

The place of such deeply beloved pieces of art are not in bare, intellectual spaces where they will be evaluated for their artistic or historical worth, but in the midst of communities where they are loved and venerated.

Recently, the reparation of stolen antiques, once there is full proof, has been on the rise. The documentation of antique theft by two art historians, Lain Singh Bangdel and Jurgen Shick, in their books Stolen Images of Nepal and The Gods are Leaving the Country, respectively, have been significant. Once proof is found, public pressure builds on owners of stolen antiques, and prestigious institutions like museums do not want to be tainted by the reputation of theft.

The same, however, is not true of private collectors. Once they have paid large sums for the objects, they incur heavy loss in giving it back, and public pressure does not have an effect. Repatriation of stolen antiques to Nepal remains a trickle, compared to its broad outward flow.

As for the idol of Digu Bhairav, there is no saying when it will come back to its temple, if ever. The residents have currently replaced the idol with a kalash, which they continue to worship as a representation of the god. Ratna Krishna Prajapati, a resident of Digu Tole, says that they have not decided to replace the idol with a new one because they are still hoping that they will get the original back. The priest, Karmacharya, however, is not so hopeful. “We had so much faith in the God, and still the idol was stolen. What can you say of God’s power now? What can mere mortals do when Gods are stolen?” he laments.

20.72°C Kathmandu

20.72°C Kathmandu