Miscellaneous

The time image

To take a photograph is to snatch a moment from the flow of time. A still photograph, a static image, is an instance separated from the arrow of time,

Pranaya SJB Rana

To take a photograph is to snatch a moment from the flow of time. A still photograph, a static image, is an instance separated from the arrow of time, preserved, as if in ember. The element of time is a critical component of any photograph. Whenever a moment is chosen and the shutter tripped, the resulting image becomes a standalone. Seen singly, divorced from the steady stream of other images, a photograph loses its context, its history and its relations with what came before and what came after.

Photography, arguably more so than even painting, is an art form that requires the viewer to take an active critical role in the construction of its meaning. This is because it purports to be reality, an objective slice of life, presented without interference. Of course, we all know this isn’t true. Barring the myriad ways in which photographs can now be altered, there is the most basic of interventions—the photographer’s eye. Each photograph is borne out of a personal vision, one eye that looks through the lens and frames the shot, relegating everything else to background noise. The frame, therefore, becomes as much about what is left out as what is left in, temporally as well as spatially.

So when faced with a claim as audacious as objective reality, any critical viewer will approach the photograph with suspicion, a desire to look through the veil and discover the ‘real’ reality. The flatness of the photograph only adds to this feeling of mistrust in the viewer— where does the secret lie if not within the object?

Further, the aesthetic quality of the photograph beguiles and provides even room for more suspicion. After all, photographs are beautiful, even when they depict ugliness or misery or death. They are made to look beautiful because who would ever want to look at a deliberately ugly picture? Whatever the content, the arrangement is always aesthetically pleasing.

All of these qualities in the photograph mean that the viewer must actively engage with the photo in question, looking beyond its frames to times past and future, in order to attempt to discern what is real and what is virtual, what is natural and what is staged, what is seen and what is unseen.

WE

In photographs like Finnish photographer Tuomo Manninen’s group portraits, this tension between the real and the virtual becomes a deliberate quality of the work. The photographs—part of the exhibition ‘We’, on display at the Photo Kathmandu festival from November 3—are of groups of professionals, from accountants to bodybuilders, in their spaces of work, surrounded by the implements of their profession. They are real people, who work their very real jobs in those very real spaces. The photographs do not lie about that. But the manner in which the people are present in the frames, artfully arranged like set-pieces on a stage, lend artificiality to these images. In the striking mise-en-scene of the photographs, there is painstaking deliberation. The photographs, therefore, are not straight-forward images of people in their natural element but rather, are constructed images of people placed in certain positions, made to look the way they do.

This isn’t by any means a fault of the photographs. In fact, it is what makes these photographs unique and interesting. The relations between the real and the artificial are there for all to see. By bringing out this tension, Manninen’s photographs are elevated beyond the ordinary and into something that serves a decisive purpose. These are not mere group portraits but active recreations of group dynamics. The tension evident here is not just between what is natural and what is constructed but between the subjects in the photos too. The manner in which the subjects are arranged speak to the tension inherent in any group, between the individual and the collective.

EVERYDAY EPIPHANIES

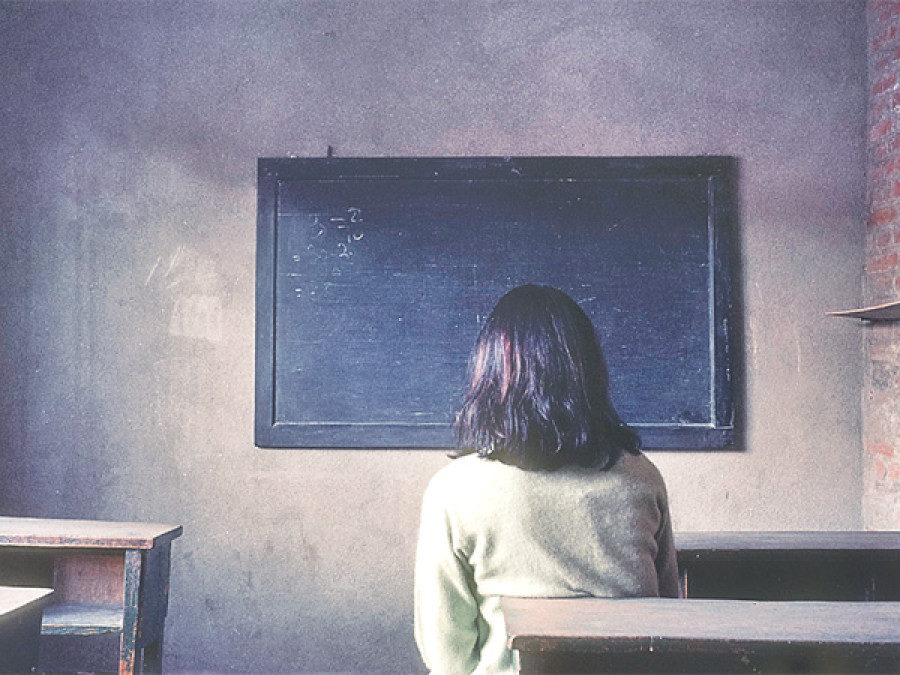

On the other end of the spectrum of Manninen, I would locate Frederic Lecloux, whose photographs are subtle meditations on the passage of time, without any seeming hint of artificiality to them. In Lecloux’s photographs, also on display at the Photo Kathmandu exhibition, it is difficult to discern where the line is drawn between what is natural and what is not. Perhaps none of them are natural or perhaps all of them are. Or more accurately, this distinction does not seem to matter, because the photographs seem to speak to some greater truth.

Lecloux’s photographs, exhibited under the title ‘Everyday epiphanies’, have a more philosophical quality. They do not seem to warrant investigation, instead they promote rumination. In the back of a head or the turn of a gaze, there is something subliminal, as if caught between the here and the now. In the seemingly banal, there is a world of thought. It is an indescribable feeling to look upon Lecloux’s photographs. It is akin to being pulled in two different directions at the same time by two very powerful horses. There is a desire to unpack these images, dissect them for all they conceal and all they make apparent. But there is an equally strong desire to simply allow the images to float down the stream of time, one decisive moment after another, one epiphany after another.

Tuomo Mannine’s We and Fre-deric Lecloux’s Everyday Epipha-nies will be on display at the Photo Kathmandu festival, taking place November 3-9, in the city of Patan.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu