Miscellaneous

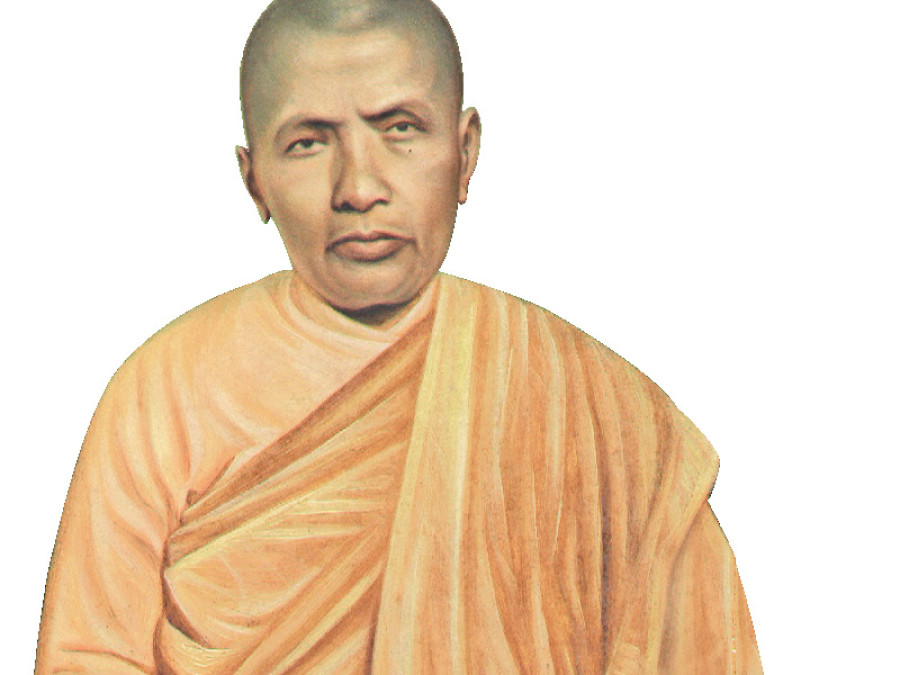

The yellow grandma

The monastery of Kindo Baha lies hidden in an out-of-the-way place, much like its history as the place from where Theravada Buddhism spread across the Valley in the 1930s. It was from this humble spot at the foot of Swayambhu hill that a few monks and nuns began revealing the teachings of the Buddha, and brought back a tradition that had been lost for many centuries. But this was not accomplished without much suffering, and the early teachers endured harassment and eventually expulsion from the country.

The monastery of Kindo Baha lies hidden in an out-of-the-way place, much like its history as the place from where Theravada Buddhism spread across the Valley in the 1930s. It was from this humble spot at the foot of Swayambhu hill that a few monks and nuns began revealing the teachings of the Buddha, and brought back a tradition that had been lost for many centuries. But this was not accomplished without much suffering, and the early teachers endured harassment and eventually expulsion from the country. Kindo Baha itself was in ruins till the early 20th century, and its renovation coincided with the reappearance of Theravada Buddhism in Kathmandu. Restored and rejuvenated, it provided the first monks and nuns a much needed sanctuary. They had a place to stay and hold prayer meets for their flock.

Unfortunately, Kindo Baha also attracted the attention of a suspicious government because of all the people coming and going. Over the years, the crowds coming to listen to the sermons had swelled into a mass, unnerving the Rana regime of the day which detested public gatherings. Theravada Buddhism, which is based on the teachings as recorded in the Pali texts, is the branch that we see in Southeast Asia. The government was used to the customary Buddhist rituals of the Kathmandu Valley, but the appearance of shaven-headed monks in yellow robes made it all jittery. As far as the authorities were concerned, anything they didn’t understand was a threat; and so they kept their magnifying glasses trained on Kindo Baha.

One day in 1931, their tolerance apparently ran out. A whole bunch of the participants were summoned to the Home Office and severely grilled. One of them was a 33-year-old widow named Laxmi Nani Bania. She was a literate woman, rare in those times, and she read from Buddhist books, taught the dharma and recited stories from the Buddha’s life. Her speaking skills and knowledge had helped to attract a large number of women to the gatherings. They took Laxmi Nani to the chief of the Home Office, and she stood nervously before him. “So you are the one who has been giving sermons at Kindo Baha despite being a woman, eh?” he is said to have screamed at her. “From now on, you will stop studying, and you will stop preaching. Do you understand?” Laxmi Nani would not be shouted down, and she reportedly asked, “Why are the princesses in the palace permitted to study? Aren’t they women too? Why should only we be forbidden to get an education?” The chief was a little taken aback by her question, and dismissed her with a warning. “You can study, and you can teach. But not in front of large crowds, so keep it inside a room. Now get out of here.”

Laxmi Nani rushed out, happy that she had not been ordered to report periodically to the Home Office as she had feared. She returned to her teaching at Kindo Baha. But barely a year later, she and the others were summoned by the prime minister to Jawalakhel Durbar. She was again told to stick to the tasks assigned to women, and not go around giving “lectures”. The harassment did not stop, and this

only made the former housewife more determined to propagate the Buddha’s teachings. She eventually made up her mind to renounce lay life and become a nun. In those days, the going was hard enough for the monks; and for the nuns, doubly so. But Laxmi Nani was made of sterner stuff. In 1934, she and three friends trekked south over the mountains to India and went to Kushinagar to be ordained as nuns. When she returned to Kathmandu in her new avatar as Dharmachari Guruma, she would lead a social transformation and inspire a whole generation of women followers.

According to Dharmachari’s biography written by Lochan Tara Tuladhar, the four women reached Kushinagar and went to the Burmese guru Chandramani and asked him to ordain them. But he thought that they should first acquire adequate training. He advised them to go to Arakan, Burma to study Buddhism and experience the monastic life before taking their vows. So they sailed off to Burma, where they studied, learned languages and begged for their food as monks and nuns were required to do. A few months later, they returned to Kushinagar after finishing their course, and received ordination and new dharma names.

Dharmachari and her

companions came back to Kathmandu in their yellow robes. When

relatives saw her in the new getup, they instantly gave her their own name. They called her Mhasu Aji, which means yellow grandma. Dharmachari went back to Kindo Baha and resumed preaching. The monastery by then was becoming a little crowded with all the monks, nuns and dharma practitioners living there. So she decided to build a nunnery for the growing number of female renouncers. The nuns pooled the alms they had saved and bought a piece of land next to Kindo Baha. There they erected a shack and established their living quarters. This was the beginning of the first nunnery for Theravada nuns in Nepal.

The rapid inroads Theravada Buddhism was making into society, and the growing involvement of women in particular, made the

government nervous. It thought that the enthusiasm would dissipate if the monks and nuns were expelled. So

in the summer of 1944, they were hauled before the prime minister and ordered to leave the country. The nuns were told that they could stay

in Kathmandu for another four months, and then they would have to go too. Dharmachari decided to appeal to the prime minister not to send them away because they were all advanced in age. Their plea was accepted; they could stay, but they would not be allowed to preach. The nuns decided that this would be a good time to get out of town for a while. So four of them including Dharmachari moved to Trishuli, a two-day walk from Kathmandu on the trade route to Tibet. There they continued to hold prayer meets, and unsurprisingly, the police sent them back to Kathmandu.

In 1946, following the inauguration of a new and kinder Rana prime

minister, the expulsion order

against the monks was cancelled. The freer atmosphere encouraged Dharmachari to develop the nunnery at Kindo. She wished to install

an image of the reclining Buddha like the one she had seen at Kushinagar where she had become a nun. It shows the master lying

down in the nirvana posture. A

suitable large stone was found at Hattiban and laboriously dragged to Kindo, where master sculptors set to work. In 1949, the 10-foot-long statue was inaugurated, and the nunnery eventually came to be called Nirvana Murti Vihar after it.

Dharmachari was getting on in years. It had been an eventful

journey from a daughter-in-law in a wealthy merchant family to a threadbare Buddhist nun. She passed away in 1978 at the age of 80. Dharmachari’s legacy, the nunnery of Nirvana Murti Vihar, stands as a reminder of the dark days of the past and a monument to her band of brave nuns.

27.62°C Kathmandu

27.62°C Kathmandu