Miscellaneous

A model from yesterday

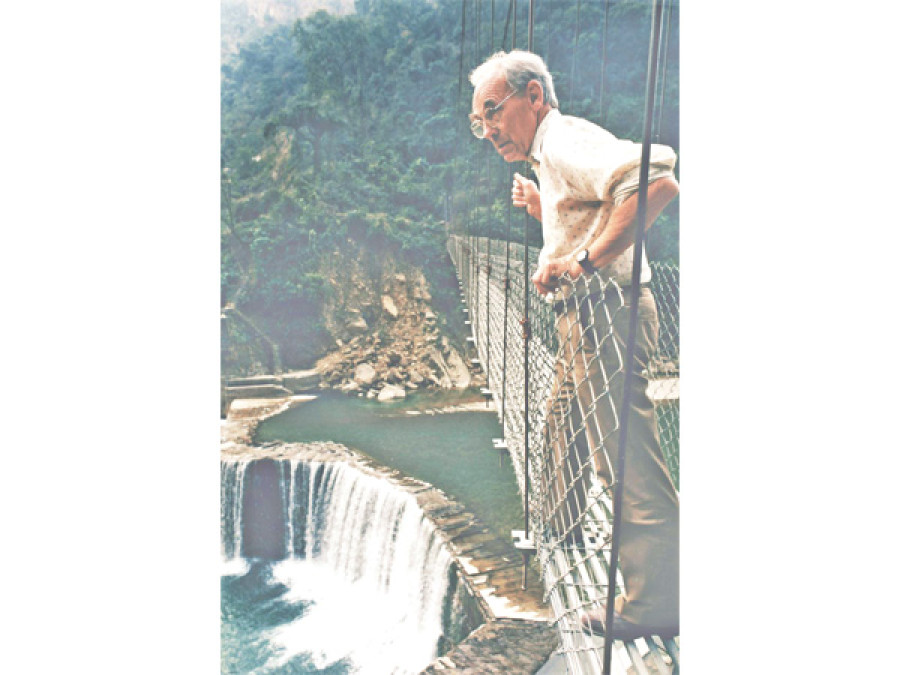

The Norwegian missionary engineer Odd Hoftun arrived in Nepal in 1958 on a brief assignment, but went on to spend more than three decades in this country, pursuing his vision of development with determination and faith.

Shradha Ghale

The Norwegian missionary engineer Odd Hoftun arrived in Nepal in 1958 on a brief assignment, but went on to spend more than three decades in this country, pursuing his vision of development with determination and faith. In Power for Nepal: Odd Hoftun and the History of Hydropower Development, published by Martin Chautari in 2015, Peter Svalheim provides a lucid and engaging account of Odd’s life and work. The book briefly charts Odd’s childhood and adolescent years in Norway, and then goes on to show how his ideas shaped the evolution of hydropower development in Nepal. It also sheds light on Odd’s personal triumphs and struggles, the growth of the Nepali church, and the

social and political changes Nepal witnessed between the 1960s and 1990s. Towards the end, the book

provides a moving portrait of Odd’s son Martin, who, despite his physical disability, was an active figure in Kathmandu’s social and intellectual circles before he died in a plane

crash at the age of 28.

Reading Svalheim’s book, it is hard not to think—here is the model of development Nepal needs, and here a man who embodied that model. Odd’s pioneering initiatives in technical training, small-scale industry and hydropower stand as shining examples of people-centered development. They are a testament to Odd’s bold vision and extraordinary spirit.

Odd’s initial years in Nepal were spent in Tansen, where he managed the construction of a hospital for the Christian organization the United Mission in Nepal (UMN). Working conditions in the village were far from ideal. But Odd met the challenges head on, remaking plans from scratch and training people on the job. By the time the hospital was

completed in 1963, Odd, then in his mid-thirties, had found another

reason to continue staying in Nepal: he wanted to open a technical

institute to train Nepali workers. He had realised that Nepal’s long-term development was impossible unless Nepali youth, who would otherwise migrate to India for employment, gained the capacity to build up local infrastructure.

Butwal Training Institute (BTI) was, in Svalheim’s phrase, a “one-time event” in the field of education and training in Nepal. It was a place where young boys from the villages learned not only practical skills but also self-discipline and respect for manual labour. Odd worked tirelessly on every front, from arranging equipment and selecting apprentices to managing the finances. Never one to shy away from dirty work, he even took his own turn at cleaning the

toilet. Over the years, BTI gave birth to a number of industrial firms that would shape the course of hydropower development in Nepal. Each of these projects began amid great uncertainty, with scarce resources and no model to follow. The innumerable challenges, tensions and

conflicts that dogged the early phases of these projects might not have been overcome without Odd’s outstanding leadership.

A striking aspect of Odd’s development philosophy was his instinctive disdain for large funds. He believed, rightly as it would turn out, that too much money hinders real progress and creates dependency. Ideally a project should always be just a little short of funds, for “the pinch triggers the imagination.” Odd was thus

constantly driven to find innovative, low-cost solutions to problems. While at the Tansen hospital, this “sworn believer in cow dung, rice straw and earth” built a rainwater storage

system to meet water scarcity, used whitewashed burlap to insulate tin roofs against heat, and designed a water-saving laundry. After he moved to Butwal, his trips to Norway were largely devoted to gathering used equipment for the workshops at BTI. So much so that his family once travelled from Norway to Nepal on a used six-ton Mercedes truck that Odd had purchased for the institute.

In his personal life, Odd adhered to the same principles that guided his work. On a visit to Butwal, a potential donor once noticed that Director Hoftun’s “personal effects were limited to a camp cot and two cups – one for himself and one for guests.” Such austere living conditions were not always amenable to family life. In a letter she wrote soon after moving to Butwal, Odd’s wife Tullis expressed her mixed feelings about her new home: “Right now, old curtains from Norway are the dividing walls between the living room and the bedroom. Packing crates make the kitchen counters and cupboards, and we have old trunks for sofas. All the same, we think life here is cozy and it will be fun to decorate for Christmas.”

As a missionary from a rich western country, Odd was acutely aware of his position and privilege. He knew people from the west are “condemned to exercise power” in a poor country and thus “doomed to be distanced” from people they need to understand. In his view, “A foreigner can be

full of good intentions, speak the

language fluently, and wear Nepali clothes. Yet everyone knows that he has a pension, health insurance,

and security back at home. At any time, he is free to go back home if he so chooses.” Beneath his confidence and strong will, Odd possessed the quintessential humility of a true humanitarian worker. Even after decades of working in Nepal’s villages, he refused to call himself an “expert” on Nepal.

For all the respect he commanded, Odd was not free from criticism. His surefooted attitude and no-nonsense approach could make him appear “gruff and blunt” to his expatriate coworkers. Some of them saw him as authoritarian and old-fashioned, and disliked the extent to which he went to reduce project costs and stick to simple means. But Odd could not compromise his fundamental beliefs. In 1971, faced with mounting opposition from his foreign colleagues at BTI, he resigned from his post as director before going on to take on new responsibilities.

Odd was to find his development philosophy articulated in Schumacher’s famous 1973 book Small is Beautiful. Like Schumacher, Odd believed that development starts not with money or goods, but

with “people and their education, organisation, and discipline.” For Odd, a successful development program was one based on a deep understanding of local realities; that exploits natural resources but also protects the environment; that pursues economic growth, but without harming the social fabric; and that places people above money and statistics. These principles lay at the core of the projects he started in Nepal.

One of the most remarkable initiatives Odd led as the general manager of Butwal Power Company (BPC) was the rural electrification project in

the Andhikhola Valley. The project, which went into operation in 1991, began with free secondhand turbines brought from Norway. True to Odd’s vision of integrated development, Andhikhola not only provided electricity to thousands of low-income families in the project area, but

also carried out initiatives in drinking water, small-scale industry,

agriculture, and reforestation. To ensure that the poorest received

electricity, the project crew designed non-traditional methods to install electricity in mud-and-thatch homes. Andhikhola thus offered an excellent model for sustainable development in a country like Nepal.

But the model did not find many followers like it should have. Instead, Odd’s ideas found less and less

space in the rapidly expanding world of development aid. Kathmandu’s “growing ghetto of diplomats, development experts, and missionaries” aroused nothing but distaste in

him. He had little control over multinational banks and private commercial interests that began to dominate Nepal’s hydropower sector. Odd’s goal of building local capacity for building infrastructure conflicted with the agenda of multilateral donors that funded large hydropower projects. In the name of ensuring quality and competence, these donors privileged big foreign companies over national firms for all major

construction works.

The two large hydropower plants that were built during the late 1990s –Khimti and Bhotekoshi–reflected these changes. For the 60MW Khimti, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) laid out donor conditions that put BPC under extreme pressure.

ADB demanded a guarantee sum of millions of dollars and wanted to reduce BPC’s share in the company to 15 percent. The 36 MW Bhotekoshi plant, financed by an American

company, was even more expensive than Khimti. It was “a purely

commercial deal, without any

concern for Nepal’s national development needs.” The project gave all the construction contracts to Chinese contractors and left Nepali firms no opportunity to get involved.

In 1993, Odd resigned from BPC partly because he found it increasingly difficult to adapt to the new

business climate. Most of BPC’s shares were eventually sold to

private donors through international bidding. Odd lamented that those who had money to invest in Nepal felt no obligation to use their resources to serve long-term public interest. Odd’s lifelong work in hydropower had turned into “a playground

for raw capital interests and huge international banks.”

Odd began development work at a time when words like “capacity building,” “bottom up” and “community-based” had not yet calcified into empty jargon. He believed Nepal had greater need for “dirty, working

people” than degree-holders in white shirts. The industrial projects he pioneered were expected to serve local communities instead of treating them as a nuisance. The times have changed drastically since. Following in Odd’s footsteps today would entail a leap of imagination and a radical departure from current development trends. Those who might rise to the challenge have much to learn from his exemplary life and work, as documented in Peter Svalheim’s excellent and important book.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu