Miscellaneous

Tracking TB cases

A 55-year-old tuberculosis patient rang up a medical centre near Ratnapark after the Great Quake to inform the medical personnel there that he was leaving for his home in Sindhuli.

Manish Gautam

A 55-year-old tuberculosis patient rang up a medical centre near Ratnapark after the Great Quake to inform the medical personnel there that he was leaving for his home in Sindhuli. This TB patient is now ‘missing’—in that he has discontinued his treatment for the bacterial infection to which almost 5,000 people succumb each year. Apart from the dangers of succumbing to the deadly infection himself, the missing man also holds the risk of spreading the disease to other people he interacts with.

After the earthquake, two other people—a 26-year-old male and another 50-year-old female—have similarly failed to show up for treatment at a TB centre in Jorpati, Kathmandu, after having already undergone almost a month of treatment. Officials from the centre have alerted the National Tuberculosis Centre (NTC) that these people have left their homes and are nowhere to be found.

These are not just the only problematic cases. At least 27 people being treated for TB have disappeared from the radar after the Great Quake. An unpublished preliminary report about the current TB situation in the country, prepared by the NTC, shows that the centre has not been able to locate these patients even after 120 days of the earthquake. This data is, however, subject to change, since the NTC has not been able to collect data from 12 centres in the far-northern parts of Gorkha, which was the epicentre of the April 25 earthquake.

Immediately after the earthquake, many people from Kathmandu returned to their ancestral homes, out of concern for their family members. Although this was simply a natural instinct that the people were showing, that behaviour proved to be a vexing problem for authorities. As people infected with TB move from one place to another, the concerned authorities are often faced with the difficulty of keeping track of these cases. If the patients do not immediately visit nearby DOTS centres, the results may be terrifying.

“A majority of people in Nepal have pulmonary tuberculosis,” says Dr Bikash Lamichane, director of the NTC. “It is important to understand that these people can potentially transmit the disease to other family members and people they interact with.”

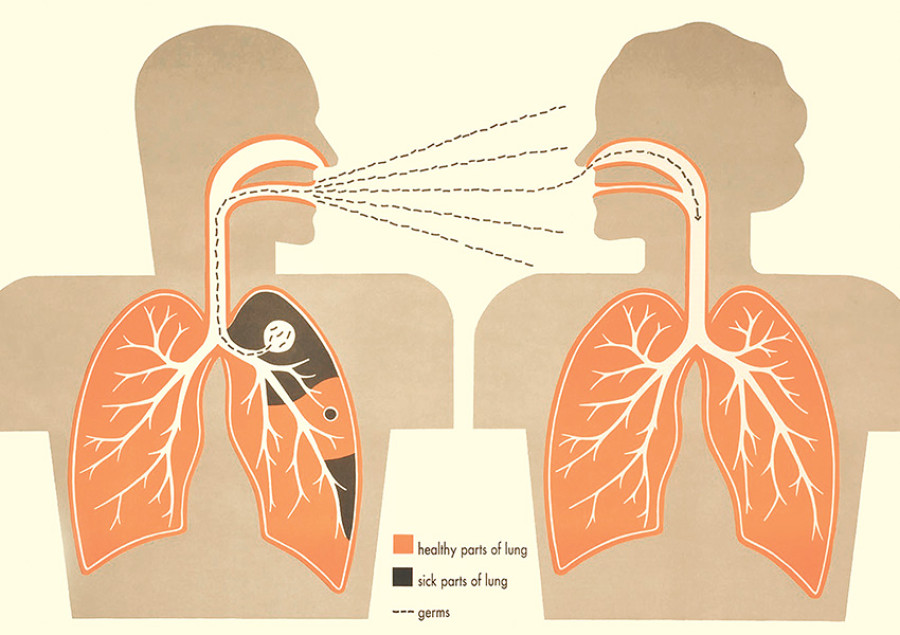

Tuberculosis is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is transmitted through the air when infected people cough, sneeze or spit. The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that about one-third of the world’s population has latent TB. This means that many people carry the bacterium in its inactive state and hence are not yet demonstrating the symptoms. However, as the immune system of the people is weakened by various factors, they start showing symptoms of the infection, and they can then transmit the disease to others.

In addition to the possibility of spreading diseases, discontinuing treatment for TB carries other risks as well. Patients diagnosed with TB are prescribed an antibiotics course lasting six months; by the end of this period, these patients recuperate if they complete the course. If, however, patients consistently adopt an erratic pattern in consuming prescribed antibiotics, then the TB bacteria develop resistance towards the drugs. As a result, treating the new antibiotic-resistant strain of the bacteria requires more expensive drugs, and at a higher dose—the cost of treatment can get as high as Rs 400,000. At present, the NTC has 349 multi drug-resistant (MDR) TB patients, among whom 151 hail from 14 of the worst quake-affected districts. Furthermore, MDR TB affected patients also pose the risk of suffering from extensive drug resistant (XDR) TB, which is caused by a stronger strand of drug-resistant bacteria, and which cost over Rs 1,000,000 to treat.

“We have been able to track down all the patients suffering from drug-resistant tuberculosis,” says Dr Lamichane. “This has narrowed down the possibilities of the disease’s getting spread.” But it is also important to note that unless the people who were being treated for TB before the earthquakes are accounted for, they could spread the disease to others, maybe even in the drug-resistant form. Nepal’s track record in dealing with TB outbreaks has improved over the years. And the days after the quakes represented a challenging scenario for the medical fraternity here.

“The authorities lacked the requisite immediate-response mechanisms to contain TB right after the earthquakes. Efforts to track down patients were also delayed,” says Dr Sushil Baral, a public health expert. “Interventions would have been effective had they been carried out in the immediate aftermath. But that would first need mechanisms such as a centralised data-bank, so that TB patients are easily located in cases of emergencies such as in the aftermath of disaster.”

The urgency shown by experts stems from cases such as those of a TB patient from Sindhupalchowk, whose medical documents and demographic details are nowhere to be found.

“What is uncertain is whether all these cases will be located and fully treated for tuberculosis,” says Dr Baral. “We could perhaps extensively deploy our female community health volunteers, who are stationed across the country, to track down the TB patients. Failing that, we have to be prepared for tough times ahead.”

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu