Miscellaneous

Man of bronze

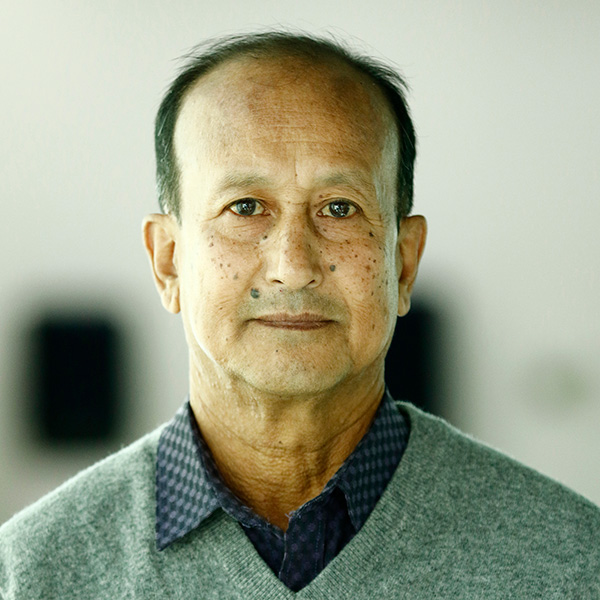

Bal Krishna Tuladhar was cast in his fatherís mould, as the saying goes. He learned to make statues from his sculptor father and went on to produce masterpieces rivalling his fatherís creations.

Kamal Ratna Tuladhar

Ratna Bahadur died in 1960 while working on the statues of another group of fine men who had sacrificed their lives for a different cause. In 1941, four activists who had been conducting an underground campaign to oust the regime and bring democracy were executed during a vicious crackdown against dissidents.

A decade later, the oligarchic system was finally dismantled, and the four heroes were enshrined in Nepali history as the martyrs of the revolution. A memorial arch named Shahid Gate was erected at the southern end of Tundikhel on which their busts were installed. Unfortunately, Ratna Bahadur passed away at his moment of glory, and it was left to his son to put the finishing touches.

Bal Krishna not only showed himself to be a true son of his father, he launched his career with a flourish. The young artist put his mark on the monument by sculpting the panels depicting memorable events from the revolution of 1951 which were fixed to the platform beneath the arch. One of the brass and copper reliefs portrays king Tribhuvan in his famous pose with his hand raised as he disembarks from a Dakota aircraft after returning from New Delhi. Another shows a mass meeting at what is now the Rangashala stadium.

ìI had seen a Dakota, but I didnít know what an aircraft ladder looked like, so I just had to guess. I put the kingís three sons at the bottom of the steps and cheering crowds around the plane,î reminisces Bal Krishna, now 80 years old, about the experience five-and-a-half decades ago. ìThe panel showing the demonstration was based on a photograph they gave me. It was so small that I had to look at it with a magnifying glass.î

Bal Krishna then lived at Yatkha, a lane to the west of Indra Chowk. He had a workshop on the ground floor of his house which fronted a courtyard. It was here that he produced his most memorable works. The ensemble of six statues placed between the staircases at the Army Pavilion at Tundikhel would be the greatest feather in his cap. Finished in the early 1960s, the statues occupy centre stage at a venue for state functions and are an illustration of Nepalís cultural diversity and Bal Krishnaís artistry. The group of statues consists of three security personnel and three civilians in traditional costumes representing the people of the Kathmandu valley, Tarai and hills. Chief Sahib Neer Shamsher had commissioned him to make them.

ìI told the Chief Sahib that I had no idea about army uniforms and accessories. So he sent over a soldier in full battle dress to model for me. The fellow used to hang around my house all day while I took measurements,î recalls Bal Krishna. ìOne day, the Chief Sahib himself came to my house to see how the statues were progressing. We scrambled to get the place cleaned up before he arrived.

Bal Krishnaís family originally lived across the street at Itum Baha where he was born. Their house was located on the southern side of the immense courtyard. The brick paved space is enclosed by houses and studded with sacred sculptures and stupas. Steeped in legend, the neighbourhood exudes a dreamy ambience. As a child, his father, Ratna Bahadur, would be constantly calling him to help with little things while he worked. Bring this, do that, hold this. That was my introduction to sculpting, recalls Bal Krishna. It was natural that I should enter the family profession and make my own statues. My elder brother became a sculptor too, but my younger brother had other plans.

And how are the statues made? ìBy the same lost wax process,î he says. The artist first makes a wax model which is covered with clay. When the clay hardens, it is heated so that the wax melts and runs out through a hole to leave a hollow inside. Molten metal is then poured into the mould, and when it has set, the clay mould is broken away to reveal the statue. This technique has been perfected over the centuries by Nepali sculptors to cast religious images, and passed from one generation to the next.

Bal Krishna has moved away from the old neighbourhood, but continues to do what he has always done despite being slowed down by age. Presently settled at Baphal, he leans back on a sofa surrounded by shelves filled with wax models while a helper hammers away at metal in the courtyard outside his window. On the wall behind him hangs a papier-mache relief of his father standing next to the lion statue that he made for Singha Durbar.

Once, Pasang Lhamu Sherpaís husband turned up at Bal Krishnaís house with a photo of the late Everest summiteer to commission a statue. She was the first Nepali woman to scale the worldís tallest peak in 1993, and died tragically on its icy slopes during the descent. The sculptor took one look at the photo and said that such a statue would be dull and convey nothing of her energetic personality. So he had a photographer take pictures of a model dressed in Sherpa costume striding forth holding the national flag aloft in her hand. ìWhen I showed the pictures to her husband, he became so emotional that he couldnít speak and tears streamed down his face. He started walking away and told me to design the statue any way I saw fit,î says Bal Krishna. Today, Pasang Lhamuís statue stands tall in a park near the Bouddha stupa, a shrine for aspiring women climbers.

From mountaineers to kings, queens and poets, Bal Krishnaís expert hands have shaped more than five dozen figures. Poet Chittadhar Hridayaís

statue at the Kalimati roundabout and communist leader Pushpa Lalís statue at Champadevi are two he recalls with fondness. One of his works, a bust of poet Laxmi Prasad Devkota, has even been flown across the Himalaya and installed in Lhasa. A prolific output most assuredly, but the sound of loud hammering outside the window tells you that Bal Krishna is not one to rest on his laurels. Like the statues at the Army Pavilion gazing out over Tundikhel, he has his eyes fixed firmly on the future.

24.32°C Kathmandu

24.32°C Kathmandu