Interviews

‘The commission is completely under the shadow of patriarchy’

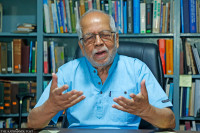

Mohna Ansari on working as a member of the National Human Rights Commission, the body’s failure to make bold changes and the rising number of rape cases in the country.

Binod Ghimire

Born in a humble Muslim family in Nepalgunj in Banke district, Mohna Ansari is the first woman lawyer from her community. She was appointed as a member of the Women Commission in 2010, thus becoming the first Muslim woman to be in a leadership role at any constitutional commission. She became a member of the National Human Rights Commission in 2014 and is retiring in two weeks completing her six-year tenure. Binod Ghimire from the Post talked to Ansari about her time at the commission and her future plan. Excerpts:

How do you evaluate your six years as a member of the commission?

I worked with total integrity and honesty during my entire tenure and performed my job in a dignified way. In the initial days, I was given a crucial assignment to oversee the entire marginalised community department and also be the spokesperson of the commission which, I felt, was a reflection of the trust in me. When there were intense protests in the southern plains at the time of the constitution promulgation, it was me who travelled from the east to west monitoring the situation on the ground and taking initiatives to calm the tension. I worked on the basis of my legal jurisdiction and mandate from the commission. The trust in the initial days, however, didn’t last long. The people in the commission gradually became hostile towards me which continues even today. I faced non-cooperation from my colleagues and also from other staff.

What I have learnt during my tenure is that the commission is completely under the shadow of patriarchy where women are always underrated. The traditional system in the commission didn’t allow my predecessors, like Indira Rana and Leela Pathak, to work independently and I went through a similar environment. That, however, didn’t stop me from raising the issues of marginalised communities, women and other human rights issues.

Do you think the commission has been able to perform its job as per its constitutional mandate?

The commission couldn’t play a proactive role. To some extent, it was limited to only issuing statements. The commission has a huge authority, almost like the courts. However, it failed to work accordingly. Hundreds of cases filed haven’t been investigated for years. The victims came to us with the hope that they would get justice quicker but we couldn’t live up to their expectation. This is gradually eroding the people’s faith towards commission which is a worrying sign.

There's a complaint that the commission suffered from the differences among the leadership. How true is that?

That is not entirely wrong. There was a hostile relationship among our colleagues to some extent, but without valid reasons. The performance of a good, united team is always better than one that’s divided, like ours. What I feel is there were no attempts to normalise the situation from the top leadership. Also, the top leadership didn’t bother to resolve the grievances of his teammates. The one in the top leadership must be assertive which wasn’t the case in ours.

The implementation of the recommendations by the commission continue to be very low. Don’t you think the commission too is partially responsible for this because it hasn’t raised its voice boldly enough?

That’s right. It is a constitutional obligation of the executive to abide by our recommendations. However, it is also the responsibility of the commission to make its voice stronger to pressurise responsible state bodies to execute its recommendations. Hardly, 12 percent of the commission’s recommendations are implemented and most of them are related to compensation. Successive governments have shown no interest towards implementing the recommendations related to the prosecution. They forget to understand that our recommendations are for strengthening the rule of law. Lately, a trend to seek reviews of the commission’s recommendations too has started.

I believe we could have formed a team to conduct a regular dialogue with the government agencies to lobby for the implementation. Also, we could have gone to the public explaining why they haven't been implemented. That could have built pressure on the executive for the implementation.

You have been in the commission in the time of Nepali Congress, which called itself democratic, and other parties—then CPN-UML, CPN Maoist and now Nepal Communist Party, carrying the communist ideology. Do these parties have similar tendencies when it comes to human rights issues or are there some differences?

The executive has pretty much similar tendencies. It hardly wants to see the empowerment of bodies like the NHRC which has the authority to keep it in check. However, in terms of access, the present executive head is more rigid. Besides formal functions, we didn’t have any interactions with Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli in his present tenure. He also seems to be very negative towards us. Also, the amendment bill to the NHRC Act, which the government has registered, shows it is not happy with the commission.

You were dragged into controversy on different occasions. What do you think are the reasons for it?

I don’t see any valid reasons for it. My statement in the 2015’s Universal Periodic Review that there are some discriminatory provisions in the constitution was blown up. There’s nothing wrong in talking about the weaknesses in the constitution; in fact, it has to go through necessary revision if necessary. The constitutions across the world have gone through amendments to raise its acceptability.

Our chairperson issued a statement when I was only defending the right to freedom of expression of the lawmaker Sarita Giri. These instances clearly show there have been people within the commission and outside who want to drag me into controversy without reasons.

The cases of rape and sexual violence have been on the rise. In your view, what factors are fueling the heinous crimes?

I believe the practice of seeking justice from the formal system is increasing despite the fact that the formal system is very lengthy and complicated. The reporting against these crimes has increased thereby showing the graphs increasing. However, those involved in the heinous crimes continue to get the protection mainly from the political parties which is affecting justice delivery. The police aren’t allowed to function independently and there are panchayats, which are associated with the political parties in one way or another, trying to settle these crimes outside the courts.

Women lawmakers are making their voices louder for harsher punishment for perpetrators of rape and sexual violence. Is that a solution? What does the country need to do?

More than having a harsh penalty, it is important to implement the existing law. There is a provision for a life sentence in rape. We have instances where the court has given 104 years of jail term. The criminal code talks about continuous hearing but the attorney general’s office has issued a directive for its implementation only on Sunday. A fast track court proceeding is the need of the hour, for it ensures there is timely justice delivery. Rather than working to have a law with stern punishment, the political leadership should vow that it will never pressurise the police and the administration to protect party cadres and relatives involved in criminal activities. The day political leaders stop protecting criminals, most of the problems will be solved.

Nepal is eying a second term as a Human Right Council’s member. Do you think Nepal has done enough to get the position again?

The Council’s membership is an issue of the country’s diplomatic lobby and geopolitics rather than the country's human rights record. There are several commitments from the last election that Nepal had failed to fulfil. There’s little progress in transitional justice and the recommendations of the NHRC continue to be ignored while nothing has been done towards strengthening the body despite the pledges made. Nepal will have to answer a lot of questions on morality, yet there are pretty good chances the country will get another term.

What are your plans after retirement?

Sadly, I am getting a tag of retirement at a young age. As I have been doing for years, I will continue to work as an advocate for human rights and social justice. Professionally I am a lawyer, therefore, there are also chances that I will get back to my old profession.

23.12°C Kathmandu

23.12°C Kathmandu