Health

Scrub typhus, a neglected disease, emerging as new health challenge

Over 260 people have been infected with the disease since the start of 2022.

Arjun Poudel

In August last year, Sunita Sharma, a local from Sainamaina Municipality in Rupandehi district, was rushed to a private hospital in Butwal, after she suffered from a persistent fever that showed no signs of subsiding. Along with high fever, Sharma, who was 33 then, also had abdomen pain and vomited frequently.

Once she was admitted to the hospital, doctors carried out multiple tests but could not diagnose the actual problem, according to Bhim Prasad Bhattarai, Sunita’s husband. “As the health condition was too serious, doctors admitted the patient in the intensive care unit,” Bhattarai told the Post.

Even after three days at the hospital, Sharma’s condition did not improve; instead, it deteriorated further. Doctors who attended the patient asked her relatives to take the patient to Kathmandu. Sharma fainted on her way to Kathmandu.

Sharma, a mother of three, was admitted at the Sinamangal-based Kathmandu Medical College Hospital where she was put on ventilator support. Doctors at the hospital too could not diagnose her problems for three days, before they suspected a scrub typhus infection. By then, the patient had gone into a coma.

Scrub typhus, also known as bush typhus, is an infectious disease caused by the parasite Orientia tsutsugamushi, a mite-borne bacterium. It spreads in humans when bitten by infected chiggers (larval mites) found in mice.

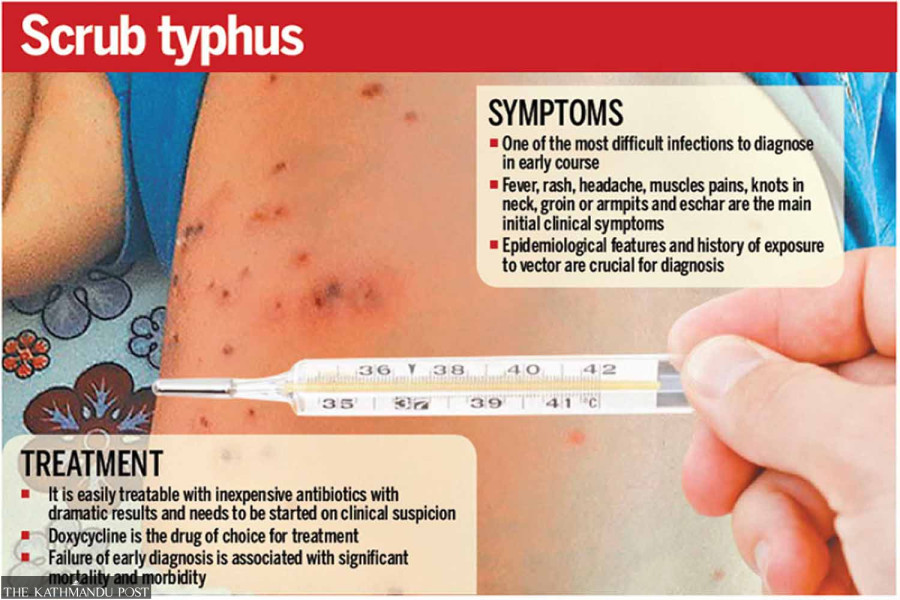

Doctors point out high fever, headache, abdominal pain, backache, joint and muscle pain, red rash, nausea and vomiting as some of the symptoms of scrub typhus infection. Patients with severe illness may develop bleeding which could lead to organ failure. The infection can lead to respiratory distress, inflation of brain, lungs, kidney failure and then multiorgan failure. If left untreated, it could be fatal.

Sharma was placed on a ventilator for 18 days and another 28 days in intensive care before being discharged from the hospital after 57 days. “Relatives who came to visit the patient had given up hope,” said Bhattarai, Sharma’s husband.

Nepal saw a surge in scrub typhus cases after the calamitous 2015 earthquakes that killed nearly 9,000 people.

Three months after the quakes, the BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan had alerted the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division about six children with unusual fever and severe respiratory problems.

Serum samples were collected for subsequent tests in Kathmandu and Bangkok that confirmed a scrub typhus outbreak. By then four children had already died during treatment. By the end of the year, 101 cases were confirmed in 16 districts and four more people succumbed to the disease.

The magnitude of the outbreak escalated in 2016—831 cases of scrub typhus were reported in 47 districts and 14 people died by the end of that year.

According to data from the Ministry of Health and Population, over 260 people have been infected with the disease since the start of 2022. In 2021, a total of 1,999 people were infected with the disease; in 2020, the number declined to 1,026.

The neglected tropical disease has been emerging as a new health challenge in Nepal of late, according to doctors.

The risk of severity and fatality can be minimised if patients are diagnosed and treated early, according to them. Ordinary antibiotics like doxycycline and azithromycin, among others, which are on the essential drugs list supplied by the government to health facilities across the country for free distribution, can cure the disease.

But what is concerning is many health workers including doctors themselves lack knowledge for the diagnosis. Many health facilities lack reagents to carry out tests for scrub typhus.

Doctors can detect the disease through the symptoms but chances of misdiagnosis are high as scrub typhus symptoms are similar to those of some other diseases.

Officials at the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, the agency responsible for containing the outbreak of disease throughout the country, concede that health facilities lack reagents for diagnosing the disease. They said the division neither has any specific plan to contain the growing cases.

“We have just developed guidelines for prevention, control and management of scrub typhus,” said Dr Gokarna Dahal, chief of the Vector-borne Disease Control Section at the Division. “We have been planning to disseminate the guidelines to all health workers serving throughout the country and organise a training on the diagnosis procedure.”

When asked about the chance of a misdiagnosis, Dahal said that it would be too late if one waited for the lab report to start treatment. He said that it takes around a week for the report of scrub typhus to come and by that time, the patient, if untreated, can go into a coma and suffer multi-organ failure.

Bhattarai, Sunita’s husband, said they spent over Rs1.2 million to save the patient, despite a 50 percent discount offered by the hospital. “Every patient cannot spend such a huge amount,” said Bhattarai. “Authorities concerned should ensure early diagnosis and treatment services in all health facilities.”

9.6°C Kathmandu

9.6°C Kathmandu