Health

Over 300 people infected with scrub typhus in 20 districts

Health workers say more cases are expected after November, but health facilities lack reagents.

Arjun Poudel

Just as the focus currently is on dengue, which has spread to 48 districts with over 6,000 people infected, there is yet another disease that is raising its ugly head, albeit slowly, but has failed to get attention and there are concerns it could be another headache for health officials.

According to the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, over 300 people have been infected with scrub typhus in the last three months and cases have been reported from as many as 20 districts, including Kathmandu.

According to data provided by the Division, hospitals in Kathmandu Valley have treated at least 63 people, including 24 children, infected with scrub typhus.

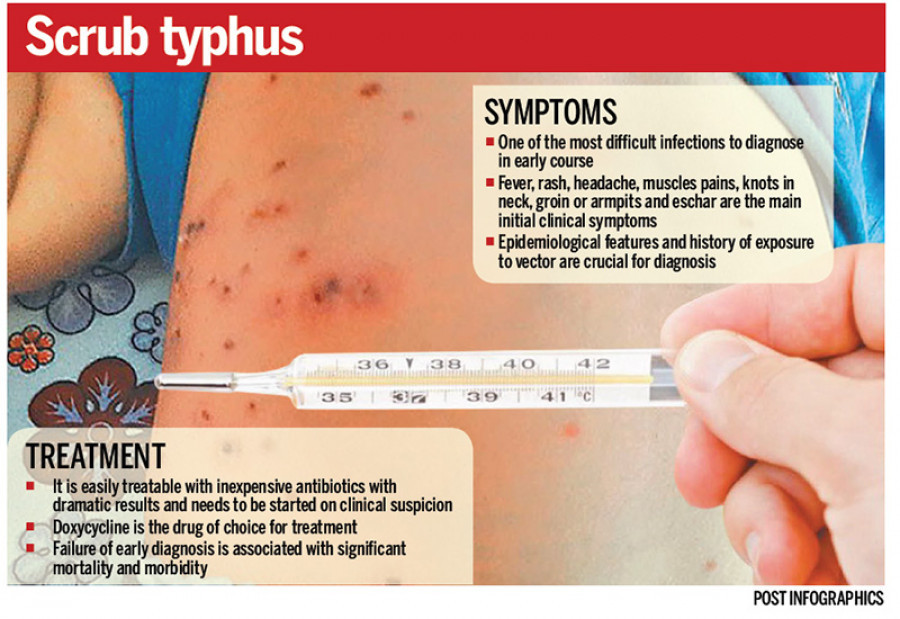

Scrub typhus, also known as bush typhus, is an infectious disease that is caused by the parasite Orientia tsutsugamushi, a mite-borne bacterium, and spreads in the human body after they are bitten by infected chiggers (larval mites) found in mice.

High fever, headache, abdominal pain, backache, joint and muscle pain, dull red rash, nausea and vomiting are some of the symptoms of scrub typhus infection. Patients with severe illness may develop bleeding which could lead to organ failure and turn fatal if left untreated.

Officials at the Division say more cases are expected in the coming months, as the disease usually surfaces during the harvest season.

“There could be more cases after November,” Dr Bibek Kumar Lal, director at the Division, told the Post. “Challenges have increased as cases of many diseases have been reported prior to the expected time and most of the hospitals lack reagents to carry out tests.”

Cases have been reported from Kavrepalanchok, Dhading, Makwanpur, Chitwan, Banke, Rupandehi, Palpa, Dadeldhura, Ilam, Morang, Kailali and Kaski districts.

According to Lal, cases of scrub typhus can be ascertained only by laboratory examination. Doctors can detect the case through the symptoms but chances of misdiagnosis are high as scrub typhus symptoms are similar to those of some other diseases, which could be fatal.

With the implementation of federalism and three tiers of government—federal, provincial and local—the Health Ministry has allotted money to buy reagents to provincial and local governments.

“Provincial and local level governments do not inform us where they spent the money that we had allocated,” said Lal. “The problem is that most of the health facilities are demanding reagents from us.”

He concedes that his office has not been able to send reagents to health facilities in sufficient amounts.

Nepal saw a surge in scrub typhus cases after the 2015 earthquakes, which killed nearly 9,000 people.

Three months after two massive earthquakes, the BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan had alerted the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division about six children with unusual fever and severe respiratory features.

Four children died during treatment as serum samples were collected for subsequent tests in Kathmandu and Bangkok that confirmed a scrub typhus outbreak. By the end of the year, 101 cases were confirmed in 16 districts and four more people succumbed to the disease.

The magnitude of the outbreak escalated in 2016—831 cases of scrub typhus were reported in 47 districts and 14 people died by the end of that year.

Dr Prakask Prasad Shah, a senior public health administrator at the Division, said that the risk of fatality can be minimised if patients are diagnosed and treated early. Ordinary antibiotics like doxycycline, azithromycin and others on the essential drug list supplied by the government to health facilities across the country for free distribution can cure the disease.

“For that, all health facilities need to have reagents,” said Shah. “Doctors can ascertain dengue infection by examining symptoms but in the case of scrub typhus, kalajar and malaria, the disease can be identified only after laboratory tests.”

24.01°C Kathmandu

24.01°C Kathmandu