Fiction Park

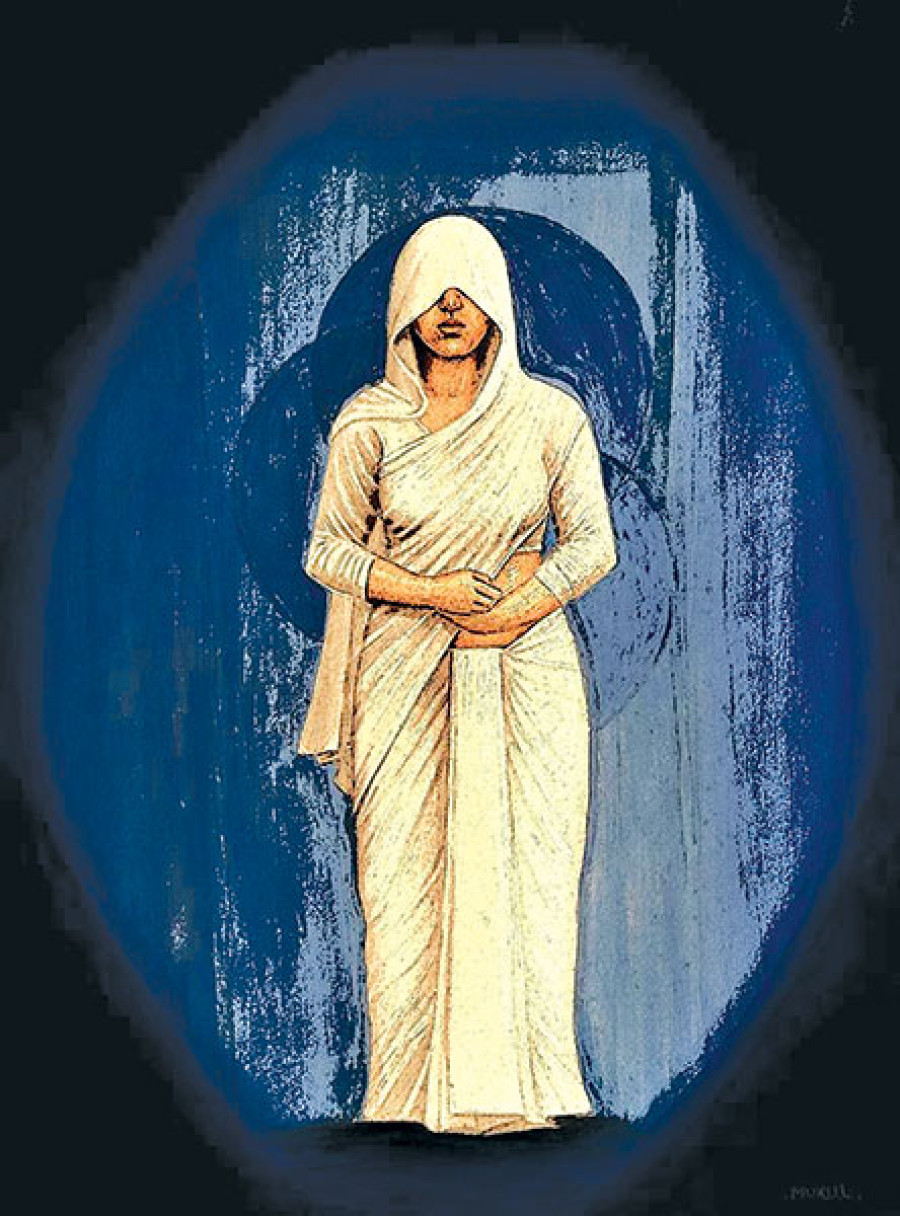

The Widow

She had been through a lot in life. She could have been anything, she could do anything, but here she was…a nokarni…who had failed to please her maliks

Sulochana Manandhar

She could never please her maliks. She would make mistakes every day, and every day she would get yelled at. I always thought, wouldn’t it be much better if she, for once, started doing a good job instead of dealing with the same tantrums day in and day out? It’s weird. Everything seemed fine on the surface-the house was clean, the kitchen was in order. Yet, there was always this friction between her and her maliks.

I had once visited that house to meet her Malikni. We were already halfway into a conversation, when Daktar Saheb asked her to fetch him a glass of water. Daktar Saheb, a doctor, only drank boiled water. She was aware of this, but that morning, it had skipped her mind altogether. There was no boiled water to serve. She clicked her tongue in regret and rushed to the kitchen. Ready to head out, Daktar Saheb grew agitated. “Don’t you hear me? I need a glass of water!” When he saw no movement, he snapped, “What kind of aimai is she? Why are we still putting up with her?”

Apparently this was routine. Malikni joined him in ranting, “I don’t know what to say…if we were to consider her age she should be well-versed in her work by now…But look at us, it’s like no matter how many times we teach her the lesson she never learns. How long does is take a person to fetch a glass?”

When she finally came out with the boiled water in a steel glass, Daktar Saheb just hurled it away. “Tai kha… I don’t want it anymore.” The glass fell and the hot water spilled everywhere. Drenched in anger, he walked out of the hall with bloodshot eyes. Malikni continued yelling, “I am tired of telling this aimai what to do and what not to do…how long have you known us for? How can you forget that Daktar only drinks boiled water?”

She just stared at the glass on the floor. Embarrassed. Guilty. “What the hell are you looking at?” Malikni snapped. She hurriedly cleared the mess and ran towards the kitchen.

Malikni wasn’t done whining. Hence, with a pair of ears to her disposal, she complained, endlessly.

“We brought her in out of pity. We thought we were saving her. She has nobody to call family after all. What a mistake-buddhi na suddhi ko aimai..”

I don’t know if she heard this at all, but when she came out of the kitchen with the tea, her eyes were moist and her face drained. She placed the tray on the table and walked away immediately.

“I have never seen a woman so dull and clueless. It’s as if she has no brains.”

I just listened.

.............

I would come across this clueless woman, time and again. Sometimes at her Malikni’s place, other times just outside on the street. The encounters were always brief and cordial. But she was a ranter too. When I asked how she was doing, her answer to my “Sanchai didi?” would sometimes be, “Nani, what can I say…I can’t live peacefully. I am just waiting for death to take me away. I can’t wait to grow older so that I can find shelter at the briddhashram. At least there, I would have someone to pour my ashes into the Bagmati.” She never had a brighter answer to this question and since her sorrow always weighed me down, I’d quickly escape the conversation. I never had the patience.

In one of our encounters, before I could ask anything she confided in me, “Nani, how I wish I had a good job to keep me afloat.” She took me my surprise, “But, you have a pretty decent job at a pretty decent household. Why would you need another job?” As if she had found an opportunity to pour her heart out onto a vessel, she continued, quickly, “Well, it is a decent household, but I don’t think I can stand living there one more day. It’s the same kach-kach every single day. They treat me like I’m not a human being. I don’t even get paid. In fact, I would throw this life away to go back to my previous life as a jyami, back then I could take pride in my sweat. Now I am just embarrassed and humiliated all the time. Living off wages is so much better than living as a servant…”

It was an endless confession. It felt like the more she talked the more retrospection she gained and hence she continued and only stopped once. I saw the same confusion in her eyes as she had when she was working at Daktar Saheb’s house. But I also saw something else, something new-integrity and desperation. But I knew I had to move, so I parted with a goodbye.

This one day, I saw the woman clad in floral dhoti walk towards me. I couldn’t recognise her until she was just ten arms away from me. As usual she joined her hands in a Namaste.

“I almost didn’t recognise you, didi,” I started the conversation casually which caught her off guard. She coyly looked around and said, “I just bought this red dhoti. I might die any day now…I don’t care about what people might say about this radical approach anymore,” but somehow along the way she lost her confidence again and looked up to me for validation, “or is it not okay?”

I didn’t know what to make of it. “No, it’s pretty and it looks good on you”

“It’s just that this dhoti is red. I don’t know if you know that I’m a widow - a bidhwa. I’m not allowed to wear colours. People are going to talk.”

I knew she was a widow but I wanted to be supportive, “It’s your body, it’s your sari. It should be none of their business. You are glowing in this dhoti.” Few minutes into the conversation, she probably felt comfortable to confide again. “Nani, binti chha… I beg of you to help me find some work. I am ready to go back to the life of a jyami - I am not afraid of labour. I will sift the sands, I will even pickup shit at kids’ schools—even that job comes with more dignity than working as a servant for heartless people. I will do anything…just not this. I don’t want to die doing this job.”

What could I have possibly done? “Didi, you and I both know it’s not so easy to find work…” I hoped this would let me off the hook. But she was not done, “Why me nani? I have had to struggle all my life. I can’t do this anymore. Kaal pani audaina!”

As she sunk in her sorrow I felt sorry for her. I said what I could, “This is the society we live in, what can we possibly do? This place is for the privileged. There never was, there never will be room for the weak ones…” She interrupted, “Haina Nani, you have no idea the pain I have been through. I was twelve when I started suffering and the tears still haven’t dried. There’s just one thing I want to do, only one thing I aspire for-an easy death, a painless death. I don’t even have anybody to take care of my dead body…all I can hope is that somebody picks it up and burns it before it starts rotting.”

Her worries were legitimate and the truth hung too heavy in the air. I wish there was something I could do about it. She had been through a lot in life. She could have been anything, she could do anything, but here she was…a nokarni…who had failed to please her maliks. Who has still putting up with the abuse. A victim of child marriage, she lost her husband at the young age of twelve. Men for her were like characters from folk tales, they existed in a world that was distant from her own. Her dreams, her aspirations, her desires … they were all shattered. She never had an opportunity to develop skills that would help her through the world. Wherever she went she was either a widow or a whore…she was an apshagun.

..............

One day I saw Malikni dropping her daughter off to school-an unusual sight. “How come you are dropping her off today,” I asked. “Well if you know someone who can work for me, let me know,” she said. “What about the widow?” To this she just laughed, “She disappeared into thin air. I had only known of tarunis eloping and disappearing, turns out bidhwas do it to.”

Had she really disappeared? Where to? Where could she have gone?

(A translation of a Nepali story originally penned in May, 1985)

14.61°C Kathmandu

14.61°C Kathmandu