Fashion

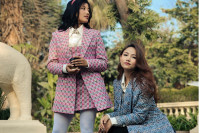

Eco-designers behind Miss Nepal’s wardrobe

As Miss Nepal 2025 approaches, here are five designers who created Miss Nepal 2023 Srichchha Pradhan’s locally made, biodegradable outfits that she wore at the Miss World pageant last month.

Aarya Chand

When Miss Nepal 2023 Srichchha Pradhan stepped onto the Miss World stage, her statement wasn’t just in the walk or the words—it was in the fabric itself. An environmental science student, Pradhan, used the pageant platform to advocate for fashion that returns to the soil.

From Malmal cotton and Nepali Dhaka to tent materials collected from Everest expeditions, her wardrobe symbolised circularity and culture. Each piece was collaboratively created with her vision and the craft of five eco-conscious Nepali designers: Danfe Works, Abir Designs, Swoniga Design, Ekadesma, and Didi Bahini Creation.

ABiR Designers Hub

Bini Bajracharya of ABiR Designers Hub contributed multiple pieces, including a cotton formal suit, a crocheted top, and an off-shoulder outfit. Materials used are silk, cotton, and pieces of fabric upcycled from the previous collection. By working with minimal-shine, natural fabrics, Abir Designs emphasised comfort and earthiness over extravagance.

The production also included contributions from women artisans working from home, highlighting another layer of sustainability: economic dignity. Instead of following mainstream fashion cycles, Abir Designs focuses on thoughtful combinations of texture and form. Their contribution demonstrated how a grounded approach to design can still produce pieces suitable for an international stage, without synthetic finishes or overproduction.

Danfe Works

Danfe Works focused on working with what they already had—existing stocks of bamboo and cotton fabrics—minimising their environmental footprint by avoiding new material purchases. The standout aspect of their contribution was the use of Mithila art, hand-painted onto garments by artists from Janakpur. Some artists travelled to Kathmandu to work on-site, making the process highly collaborative and grounded in cultural exchange.

Instead of designing for visual spectacle, Danfe centred their efforts on simplicity and meaning. A single Mithila hand-painted skirt took over three days to finish. Several outfits included patchwork from leftover fabric scraps, turning potential waste into something wearable and symbolic. The designs were produced in partnership with SAATH, a social enterprise the brand has worked with for years, ensuring that each garment supported both sustainability and livelihoods

Swoniga Design

When Pradhan approached Swoniga Design, the timing was last-minute. As a result, the outfit she wore was pulled from the label’s ‘Kathmandu Fashion Week 2024’ collection rather than being designed anew. Fortunately, the fit was seamless—both literally and conceptually. The collection had been based on the elements—earth, air, fire, and water—themes similar to Pradhan’s environmental advocacy.

Materials like linen, cotton, and silk were chosen for both their aesthetic and low environmental impact. The visual symmetry between Swoniga’s seasonal collection and Srichchha's personal advocacy made the pairing intuitive. Swoniga’s strength lies in detailed finishing—draping, hand-stitching, and trims—which brought depth to the design without needing synthetic embellishments.

Ekadesma

Ekadesma created two original outfits for the pageant—one in 100 percent cotton and the other in a hemp-cotton blend. The design process was intentional. Zero-waste techniques were used to craft 3D floral appliques from fabric scraps. No synthetic elements were added, and the garments emphasised texture, form, and careful tailoring.

All production occurred in their Kathmandu studio, where women artisans carried out each step—from sourcing to pattern-making to final detailing. Ekadesma’s contribution reflected its long-standing commitment to slow fashion and craftsmanship.

Didi Bahini Creation

Didi Bahini Creation used Matka silk and organic cotton to transform traditional handloom weaving into structured silhouettes for the pageant. The lightweight, breathable, and richly textured fabrics reflected a deep connection to heritage techniques.

The production process was meticulous. From sourcing silk threads to handloom weaving, every step involved skilled artisans working in a slow, measured rhythm. Adjustments had to be made along the way to accommodate the irregularities of handwoven fabric, which often comes in small batches with slight variations.

Rather than seeing this as a limitation, the team adapted their designs to highlight these natural inconsistencies, giving each piece a distinct character.

“I wanted my clothes to return to the earth,” Pradhan said. “To nourish the soil.” Her wardrobe reflected that ethos—biodegradable, handwoven, culturally grounded, and created through processes that centre people, not profit.

9.6°C Kathmandu

9.6°C Kathmandu