Fashion

How sustainable is sustainable fashion in Nepal?

Designers are showcasing designs made from donated clothes and a ‘sustainable fashion show’ is set to be held at Kala Patthar early next year. But how truly ‘green’ is their approach is up for debate.

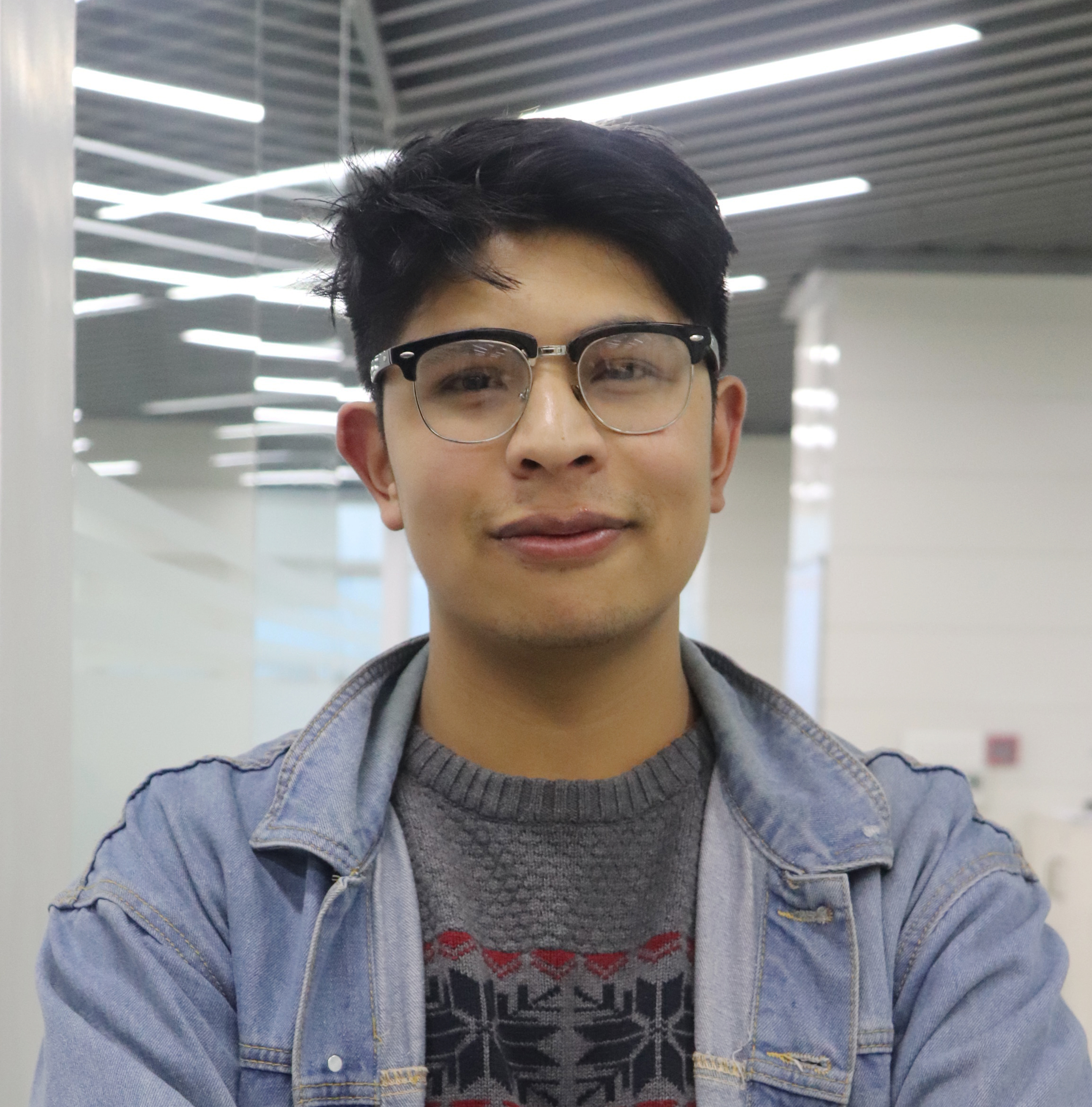

Ankit Khadgi

A recent fashion show showcased top Nepali models wearing dresses designed entirely by donated clothes. The concept of the event organised by The Clothing Bank, an organisation that has been collecting used clothes for the last four years by keeping open cloth stations in and around the Valley, was a novel one. While not all dresses flaunted by the models were able to make the desired impression, the charity event did accomplish what it had set out to do—to introduce the concept of using a product to its complete lifecycle.

"We just wanted to promote upcycling of clothes,” says Shree Gurung, one of the organisers. “We just hope that this will encourage people to take a sustainable approach when it comes to fashion, rather than seeing items of clothing as something you dispose of after they’re out of style.”

The concept of sustainable fashion, which has been recently popularised as ‘slow fashion’, is a global phenomenon, and it is slowly gaining popularity in Kathmandu as well. Slow fashion pertains to minimising the environmental effects brought in by an abundance of fashion choices, quick change of styles and trends and affordability. According to Business Insider, the fashion industry alone is accountable for 10 percent of global carbon emissions.

To combat this problem, there is a call for awareness among both manufacturers and consumers to adhere to higher sustainability and ethical standards. The trend of ‘slow fashion’ is definitely in vogue with many internationally famed designers committing to a sustainable approach towards fashion. In Nepal, some are even taking unique steps to introduce local consumers to this growing and impactful trend.

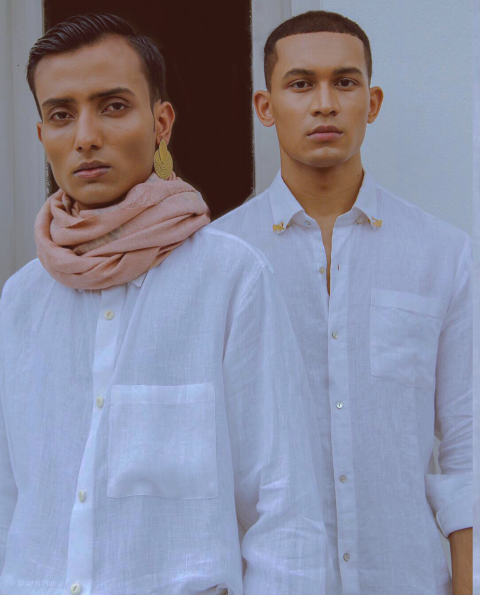

One of the biggest events that have been hugely publicised as a sustainable fashion show is ‘Mt Everest Fashion Runway’ to be held at Kala Patthar in Khumbu region, which is at the altitude of 5643 meters, on January 25, 2020. Organised by Kasa Fashion Wears, the event aims to promote Kasa as a brand in the world market for sustainable and biodegradable fashion, says owner and designer Ramila Nemkul. Twenty models will walk the runway, among which 15 are international models from Italy, the Netherlands, Finland, Poland, Nigeria, Mexico, Sri Lanka and India.

In order to ensure that they follow a sustainable approach, the organisers have taken various steps. They will be showcasing designs made using felt wool and pashmina, which they claim to be biodegradable. But how truly sustainable is their approach remains to be seen.

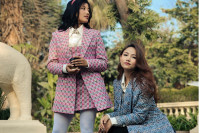

While Kasa Fashion Wears is making use of these designs just for this event, another startup, Bora Studio, has been using natural fabrics like bamboo, hemp, and nettle to manufacture all their products—from jackets and blazers to shirts.

Meena Gurung, the founder of the fashion brand, says that they are extremely mindful of everything that goes to making their products, down to the usage of dyes. Bora Studio stays away from chemical dyes, which are commonly used in fast-fashion clothes. Ditching the dyeing process that pollutes water and the ecosystem, Gurung has been using the natural ways, like boiling and steaming leaves of eucalyptus trees, pits and skin of the avocado, and others to extract colour to dye her clothes.

“I even dye the clothes myself through natural ways,” says Gurung.

But despite her efforts to popularise the use of ‘green’ fashion, she admits that most of her customers are foreigners. “We mostly cater to international customers because Nepalis aren’t aware of the adverse effects of our fashion choices,” she says. “We need a lot of awareness around these issues.”

Sajna Jirel, programme manager at HattiHatti, another sustainable brand, agrees with Gurung.

HattiHatti’s concept is very similar to the fashion show organised by The Clothing Bank, but rather than making runway clothes, they specialise in making everyday clothes, like kimonos, ties and even cushion covers from upcycled sarees or other fabrics.

“People have become more accepting of sustainable clothing,” says Jirel. “But we need more awareness on this issue.”

The Mt Everest fashion show is one such attempt to bring sustainable fashion to the forefront, says Nemkul. But organising a fashion show at the base of the highest mountain, which is already been trashed and polluted by the increasing number of mountaineers, has raised questions on how sustainable their approach really is.

Nemkul said that their 50-member team—including models, organisers and guests—will reach Kala Patthar by walking through the trekking route to the destination from Lukla to reduce the participants’ carbon footprint. The team will also not buy any trekking gear, instead, they will rent them to promote sustainability.

Going even further, they will be using waterless bathing technology at Kala Patthar and use pro-biotic detergent, soap and dish-bar so that they don't leave behind any chemicals in the soil and water bodies.

The one-time-use AA batteries, which will be used by the documentary team, will also be brought back to Kathmandu and handed over to the municipality so that they can be properly disposed of.

When asked about the amount of carbon footprint the international models will be leaving behind because of their flights to Nepal as well as the footprint of the entire team’s flight to Lukla, Nemkul says that the flights will not have any additional adverse effects on the environment.

“The number of carbon emissions produced by international models’ travels will be the same even if we organise a show in Kathmandu,” she says. “The right move is creating balance, which we are doing, as the international team will plant more than 100 trees.”

Nemkul’s claims can make one sceptical, but she is adamant that this promotional event will help people realise the impact of slow fashion. “There is a lot of scope for sustainable fashion in Nepal. We are just trying to highlight that,” she says.

Whether these promotional campaigns and events will raise awareness among the general public is yet to be answered. Only after the lack of variety of sustainable fashion brands is addressed and the social stigma attached to using recycled clothes is overcome can this trend be a generally accepted norm in Nepal.

Although the fashion show by The Clothing Bank organised in a five-star hotel in the Capital was attended by prominent personalities, the pickup places set up as ‘cloth banks’ in various parts of the Valley had no takers just a few months ago. The locals said that people were only willing to take clothes in the evening, after it gets dark, possibly to avoid being seen.

“This is what we wanted to dispel,” says Gurung during the event.

21.56°C Kathmandu

21.56°C Kathmandu