Editorial

Tripping on TikTok

Both the ban on the social media app and its lifting have been arbitrary.

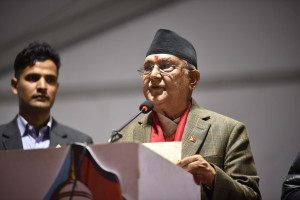

Exactly a year ago, the then Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led government banned TikTok after introducing the ‘Directives on the Operation of Social Networking 2023’. Many considered this an attack on freedom of expression. Just when people seemed to have grown accustomed to the ban, the current KP Sharma Oli-led government lifted the nine-month restriction on the platform on August 22. Last week, TikTok finalised its registration process in line with the 2023 directives. With the video-sharing platform officially registered and operational in the country, the debate around it seems to have subsided. But how does registration make the platform better, and why was the ban implemented so suddenly if it was going to be reversed just as swiftly?

According to the Internet Service Providers Association, TikTok accounted for nearly 40 percent of the country’s internet bandwidth, with around 2.2 million users in Nepal before the ban. Unlike countries like India, which decided to ban TikTok citing privacy and security concerns, the intent of “stopping and curbing social ills and anarchy” was the sole reason highlighted by the Nepali government while banning it last year.

Previously, the government stated that registration was necessary due to a rise in user complaints and the absence of company representatives in the country, which made it challenging to address concerns. Now, although our laws apply to TikTok within our territory, it remains unclear how action will be taken against legal violations. In fact, the regulations in place are not sufficient and clear enough for proper implementation. The Electronic Transaction Act, 2063 (2008) does not address specific cyber-related crimes and emerging threats such as revenge porn and online prostitution. Further, the 2023 directives specify that the point of contact must identify content that violates the guidelines, such as material promoting obscenity, vulgarity, or hate speech. However, these terms are left open to interpretation, as they lack clear definitions.

Although the Cyber Bureau can collaborate with TikTok to take action, a recent Post report revealed that the bureau is critically understaffed and underfunded, with only 106 personnel. Among the staff, only a few are capable of solving cases, while the remaining ones are given administrative duties. What’s intriguing is that TikTok alone was scrutinised and banned, although the directives mandate that all social media platforms register with the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology. The video-sharing platform is only the third company to register with the ministry in Nepal after Viber and WeChat. According to the prime minister, social media platforms must be treated equally, so why are Facebook, X and Instagram, with 10.58 million, 4.66 million and 3.60 million users, respectively, allowed to operate without registration?

The Australian government recently announced a ban preventing children under 16 from using social media, a decision that was met with harsh criticism. Meanwhile, in Bangladesh, the interim government’s repeal of the draconian Cyber Security Act—previously used to curb press freedom—was widely welcomed. These examples show that countries around the world are experimenting and finding ways to address the challenges of a rapidly evolving digital landscape. Social media platforms are interconnected and constantly shifting, with features like short-form videos, once unique to TikTok, now available across other platforms. This suggests banning platforms may not be the most practical way to address social media’s negative aspects. Rather than relying on populist measures, our government should invest in digital literacy and research to create thoughtful, viable regulations. Moreover, the law should apply to all rather than randomly selected platforms.

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu