Editorial

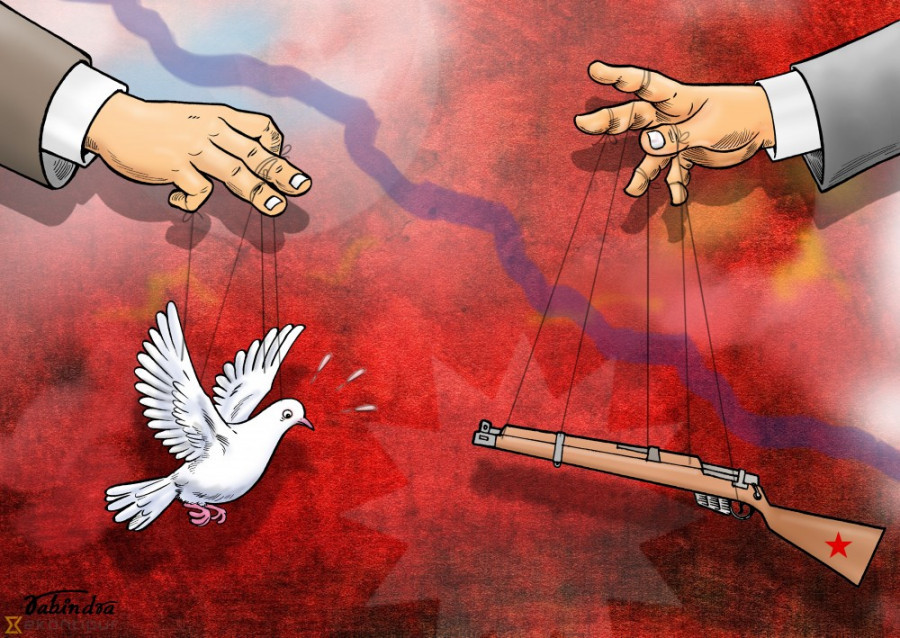

Justice as elusive as ever

The government has been leading the conflict victims in circles.

The two transitional justice bodies—Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP)—have been without office bearers since April 14, 2018. Victims of the Maoist conflict have long complained that they have been neglected, and they have warned that they will not accept the transitional justice process if the new leadership in the two commissions is selected without proper consultation.

But on Saturday, showing no consideration for what the conflict victims, human rights defenders and the international community had been warning the ruling party against, the top leaders from the Nepal Communist Party and the Nepali Congress reached an agreement on appointing officials to the two transitional justice commissions.

Ganesh Datta Bhatta and Yubraj Subedi--the chosen ones to lead the truth commission and the disappearance commission respectively—are apparently known party loyalists having their allegiance to the Nepali Congress and the Nepal Communist Party. Nepal’s transitional justice process was already botched. But with these appointments, the government and other political leaders have made clear their intention to weaken war-era crimes and absolve themselves of the heinous deeds. The victims of Nepal's decade-long civil war (1996-2006) claimed that government processes are ‘cursory’ and the recent appointments are a testament to it with the culture of impunity proving to be even more stubborn.

During the years of the insurgency, more than 16,000 people lost their lives and scores are still missing. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement had envisioned the formation of the two transitional justice mechanisms within six months of signing the peace deal. But due to political wrangling associated with the perpetrator’s fear of prosecution, it was formed only nine years later in February 2015.

Regrettably, the government has failed to learn from its past mistakes. The commitment has to come from the government to ensure accountability for human rights abuses committed during the armed conflict. While the government has made a few amendments on the legislative front, the process of transitional justice must be more inclusive. There are no second thoughts about this. What’s more, the Universal Periodic Review—a process involving a review of the human rights records of all UN Member States—is due this year in November. Given the new appointment, Nepal is bound to be grilled by the international community for its choices.

Our leaders have often touted Nepal’s peace process to be a homegrown, nationally led process. But there is nothing accommodating about the recent decision that has only shown its indifference to being inclusive in the process of ensuring justice and closure to the victims of war-era crimes. Transitional justice is associated with a society’s attempt to come to terms with past abuses, ensure accountability, serve justice and achieve reconciliation. But the latest development fails to provide meaningful hope of justice for the victims in conflict-related human rights violations as they continue to face challenges. Their uncertainties have been renewed.

15.14°C Kathmandu

15.14°C Kathmandu