Columns

Town and country

The Pakistan floods must be seen in the context of an already dire situation.

Aasim Sajjad Akhtar

“The antagonism between town and country begins with the transition from barbarism to civilisation, from tribe to State, from locality to nation, and runs through the whole history of civilisation to the present day.”

— Karl Marx

Having ripped through Gilgit-Baltistan, Kashmir and KP, the now annual wave of monsoon-triggered flash floods is wreaking havoc in Punjab, laying bare the disrepair of the rural countryside. Beyond tokenisms, neither Pakistani officialdom nor the commentariat has taken notice.

The contemporary rural-urban divide is certainly not the same as it was some decades ago. Pakistan is the most urbanised country in South Asia; around half of its population lives in towns and cities, or villages that resemble urban settlements. Crucially, however, the rate of urbanisation reflects the fact that many working people are forced to migrate to urban environments because of a deep agrarian crisis.

Indeed, an entire analytical category — that of climate migrants — is now in currency to capture the experience of those who are forced to leave their homes and livelihoods due to environmental change. The vast majority migrate from rural to urban areas. We still have no data on how many of the almost 40 million displaced by the 2022 floods have moved permanently away from their rural abodes. In any case, rural Sindhis have been migrating in historic numbers to Karachi and other urban centres in Sindh since the floods of 2010 and 2011.

More generally, pastoralists, small and landless farmers as well as workers in non-agricultural occupations are unable to meet their livelihood needs in the face of ever greater concentration of land, the influx of capital-intensive technologies, the monopoly power of multinational agribusiness and the complete abandonment of pro-poor public policy. Landlordism and attendant forms of statecraft are, of course, colonial legacies. But contemporary forms of capitalist agriculture, urban sprawl in the form of real estate-isation as well as newer colonial modalities like mineral, land, forest and water grabs in ‘dry’ rural zones have made the class war even more acute.

Entire villages in rural KP and Punjab are conspicuous for the complete absence of working-age men who have migrated either to metropolitan Pakistan or foreign destinations like the Gulf and southern Europe. It is another matter that these young men face innumerable trials and tribulations in what they hope to be ‘greener pastures’; consider only the increasing incidence of deportations or deaths during harrowing journeys at the hands of human smugglers.

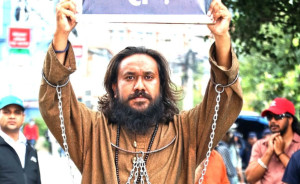

Floods and other climate breakdown events must then be seen in the context of what is an already dire situation. The news cycle encourages urbanites to feel sympathy for the worst affected, but many of the same chattering classes who might even donate to flood relief articulate support for brazen class war against migrant labourers in metropolitan centres.

In Islamabad for instance, what the authorities call ‘encroachments’ (read: katchi abadis) are once again the target of evictions in the name of curbing urban flooding. It is true that many informal settlements are made on riverbeds (nullahs), but it is often the formerly rural poor who became the urban poor in metropolitan environs. Just like the state is least interested in formulating a meaningful, long-term policy to address the agrarian question, it is similarly unconcerned about the fate of working people in urban Pakistan. Indeed, as the raging waters inundate Sialkot and other Punjab towns, even the much-hyped ‘middle classes’ are literally at sea.

Which is why it’s necessary to go beyond the shallow nature of what we call ‘public discourse’. The militarised ruling class is not interested in substantive critique, let alone revamping its policy matrix. It will continue giving free licence to rural and urban landlords, speculators, big industrialists and the mythical ‘foreign investor’ in the name of fantastical schemes like corporate farming, riverfront development and ‘green tourism’.

The rest of us, especially those who are committed to the basic freedoms and future of working people in the rural countryside, cannot simply rely on highlighting the ravages of class war, including the destruction weaved by floods and other such events. An alternative political and economic imaginary must accompany the online outrage.

The floods this year could yet cause destruction all the way down the Indus. The rural poor would be the worst affected. But to be poor is not an innate condition or fate. Poverty and inequality, particularly in the countryside, are produced by the nexus of class and state. That is why we still need land redistribution, food support prices and regulation of agribusiness.

-DAWN (Pakistan)/ANN

15.12°C Kathmandu

15.12°C Kathmandu