Columns

Climate actions on domestic front

We must evaluate how we're faring domestically in our climate actions.

Madhukar Upadhya

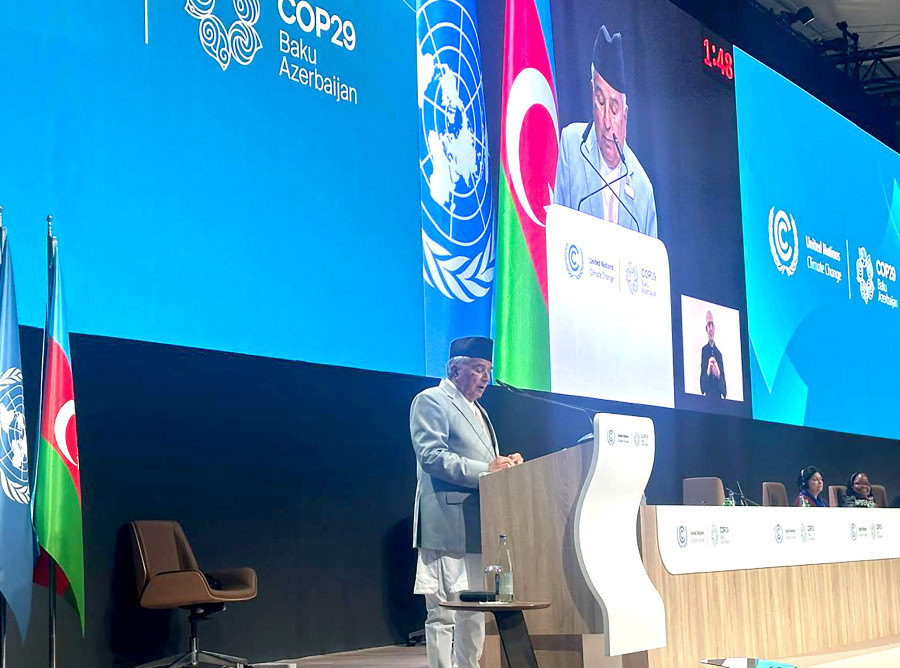

With the 29th annual Climate Conference of Parties (CoP29) currently underway in Baku, Azerbaijan, the hopes are again that it will deliver concrete outcomes on emissions reduction and climate finance pledges made at previous iterations of the event. Despite this, many climate experts believe CoP29 is more likely than not to end with another round of verbose promises and little action following these contentious issues for two reasons.

First, the US election results have dampened its spirit; even now, rumours are brewing that the incoming administration will go the way it did in its previous term and abrogate the Paris Agreement (PA). The prospect of cutting emissions to maintain the global temperature below 1.5 degrees Celcius is already falling short as there are no signs of the promised fossil fuel transition—rather, it’s expected to rise by 0.8 percent in 2024. Second, countries must agree on a new collective quantified goal for financing climate actions in developing countries, which states had agreed to set by 2025 in the PA.

This is perhaps the prickliest issue for negotiators as ample differences persist among the parties regarding the fund size, its contributors, types of finance and their funding modality and the overall duration. What's become clear is that all of this funding won't be grants, which developing countries have consistently demanded. Still, it may include provisions to mobilise funds through various other sources, including the private sector, carbon trade, and so on. So, what is next for us?

We can hope to receive the required financial support from global sources to conduct some of the conditional activities of our nationally determined contributions and provide reparations for the losses incurred after climate-induced disasters. However, we must evaluate how we're faring on the domestic front in our climate actions. Several seemingly small but important initiatives we haven’t considered so far must support the vulnerable in tackling the climate impacts.

Important initiatives

The National Climate Change Survey (NCCS) report published earlier this year drew our attention to key climate impacts; unfortunately, our priorities fail to match them. For instance, the government has noted the striking examples of floods in Melamchi, Mustang, Thame and Kathmandu as evidence of the climate impacts facing the country. While not denying their seriousness, the NCCS ranks floods as the fifth most common climate hazard affecting households—droughts are the most common. A staggering 65 percent of households and their farms have been continually affected by droughts for the last 25 years. Meanwhile, only 0.2 percent have practised rainwater management to address the problem. Second on order are insects and diseases in agriculture, which affected 54 percent of households but missing from the concerns as prioritised by the government.

For better planning and preparation, additional research could further inform our contingency plans. Such evidence-based, well-informed plans will be crucial, especially since we’re increasingly anticipating dry winters and frequent dry spells following the first few weeks of monsoon, as seen in recent years, resulting in low production of winter crops and drying of newly planted paddy. Considering the increased frequency of late monsoon floods and the escalating scale of losses each year, what strategy would help farmers salvage harvested paddy from flooded farmlands? As an army of people is needed to recover paddy drowned by late monsoon floods, the lack of available labour often adds to farmers’ grievances. In 2021, the nation lost paddy worth Rs11 billion.

Sadly, even our well-intentioned water supply programmes seem maladaptive when implemented without adequately understanding the problem. The boreholes introduced in the parched hills to provide water are an excellent example of this phenomenon. They were promoted without any meaningful attempts to revive drying springs. Boreholes can turn maladaptive when the lower aquifer dries out due to over-pumping, leaving communities with no other local sources to fall back on.

Loss and damage funds have been Nepal’s key priority at major international climate talks. However, attributing losses to climate change will require credible evidence over a reasonable period since most of these being considered for reparations, be they from Glacial Lake Outburst Floods or cloudburst-triggered floods, were occurring in the past as well, albeit less frequently. Efforts need to be directed to generate the required evidence for attribution.

GESI responsive adaptation

Climate responses must consider gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) to address the differential climate impacts that vary across diverse geographies, populations and cultures. Therefore, Nepal’s climate change policy has made GESI integration one of its primary objectives. However, this is often inadequately reflected in annual programmes and budgets except in a few dedicated projects. Therefore, even after implementing projects with clearly identified GESI issues, they cannot reveal how effectively the differential impacts have been addressed.

Tackling these impacts measurably requires making GESI an integral part of the planning and implementation cycle so that evaluating climate investment and reporting on the progress in reducing the vulnerability is possible. It will also facilitate non-state actors, such as civil society organisations, to raise questions to make the public sector accountable for prioritising GESI in climate response and, in the process, set in motion the course of consolidating the varied experiences of GESI integration across the board.

Our planners use such feedback from non-state actors while formulating plans for the future and improving the governance of GESI-responsive climate finance. Otherwise, the differential impacts will continue to affect vulnerable communities disproportionally. This is why global climate funds generally consider GESI an important condition when funding climate projects.

Focus on the domestic front

Given the lacklustre and almost callous response of high carbon-emitting countries in taking radical steps to drastically cut emissions, as agreed in the PA and reiterated by climate scientists in the intervening years, it shouldn’t be surprising that many experts have concluded that CoP summits are ‘no longer fit for purpose’. Their pessimism seems warranted considering the disproportionate representation of fossil fuel lobbyists at these events hosted by petro-states and the alarming uptick in floods, droughts and wildfires globally. Recent flooding events worldwide, including in Spain and Nepal, demonstrate how violent they've become lately. With the Government of Nepal spending a substantial portion of its budget to fund climate-related programmes, we must begin focusing on the domestic front to implement our set climate policy and improve its governance effectively.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu