Columns

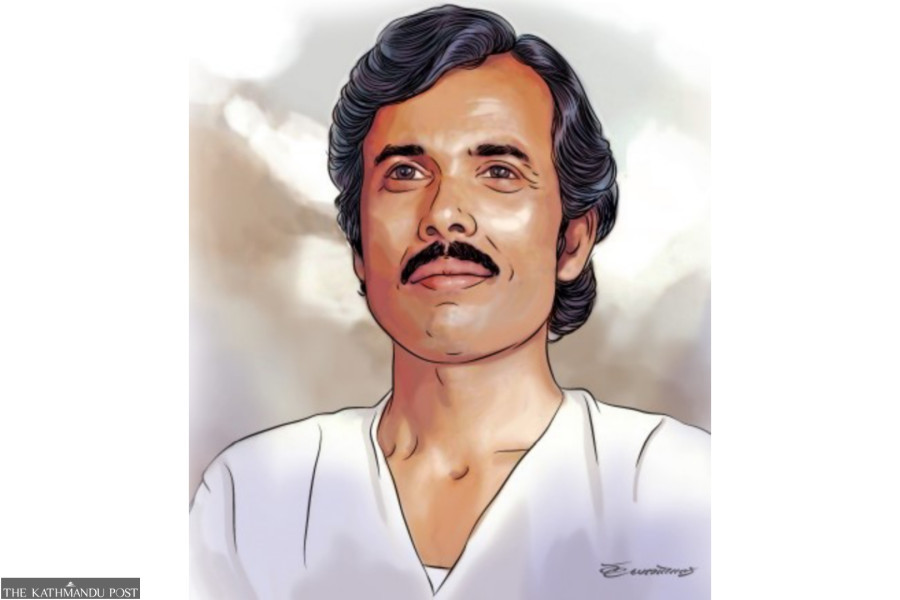

Bhakta Raj Acharya’s musical times

The range of his singing from ‘sugam’ and choir to ‘bhajan’ was remarkable.

Abhi Subedi

The coincidence of the famous musician and singer Bhakta Raj Acharya’s death at 81 and the 86th anniversary of the musical maestro Amber Gurung occurring the same day, 26 February 2024, struck me. This becomes more eloquent when we evoke one musical event in 1973.

The Wikipedia text says, “Acharya won the gold medal in an All Nepal Song Competition held by Radio Nepal in 1973” for the song Hosiyar, yes bakhat samayako mukhalai china or “Beware and recognise the true face of time at this juncture.” The composer and writer of the song, Gurung, also received a gold medal. According to musicians Aavaas Phuyal and Kishore Gurung (son of Gurung), that was Acharya’s first recorded song. After that, he got a job at Radio Nepal, which he held until 1986. In his lifetime, he recorded 450 songs and composed 25-30 songs. Such a massive output during a short period represents Acharya’s dedication, talent and sadhana towards music.

To dwell a little on the meeting of Gurung and Acharya, we should turn to the time when a few important events took place in Nepali music. Several musicians from Darjeeling came to Nepal; some settled here permanently. Gurung moved to Nepal permanently around that time. Acharya also “came to Nepal in 1970 after spending 31 years of his life in the Dooars tea estate.” (Wikipedia). Another prominent musician and singer who moved to Nepal was Gopal Yonjan. I am alluding to this diasporic movement of talented Nepali performance artists only to indicate the changes, styles and experiments they introduced to Nepali music and singing during that time. The stylistic innovations that Gurung, Yonjan and Acharya made hugely impacted Nepali songs and composition. They made experiments in musical forms, songwriting and singing.

For example, I want to briefly describe a musical performance and experiment by Gurung. That was his performance of a Western musical form known as a “cantata” involving several singers and choirs. Gurung introduced this Western classical narrative musical form, which was a big surprise in Nepali music. The sacred cantata made prestigious by the German Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was not a familiar form here. Gurung did not have any repertory at the Nepal Academy where he worked. This cantata, whose libretto was written by poet Ratna Thapa, was perhaps a one-time experiment. Naturally, this form did not receive continuity except for a modest attempt by Gurung himself to introduce a choir five years later. However, his student Phuyal, who performed a cantata titled “Neel Chari” on September 11, 2014, gave continuity to his legacy. Phuyal wrote both libretto and music for the cantata.

I recall my first encounter with Acharya around the cantata performance and the choir. The modulation of his voice had impressed me. I did not know much about Acharya’s association or apprenticeship with Gurung. Evidence shows Acharya did develop his own form of music writing and singing. His melodious voice and the ease with which he sang made him a strong singer and musician at the same time. One can hear Acharya’s songs online, as I often do, and get impressed by his voice and the music he has composed for the words. There is no point in repeating the titles of the songs and their contents here because they are so readily available thanks to the modern technical innovations and online facilities that did not exist when singers and musicians of yesteryears were working. This new development has made all the difference in musical composition and dissemination.

As an example of the quality of Acharya’s music and singing, a well-known song he composed and sang is worth mentioning. I must have sung this many times, among other songs that have perennially energised me while working on my articles and books and in my free creative moments. The song is Hajar sapanaharuko maya lagera aunchha, or “Oh, how I love my thousand dreams and feel the surge of a longing to live again”. Poet Ishwar Ballabh dai wrote this powerful lyric. He wouldn’t get tired of mentioning the song, the music and the singing of Acharya in conversations with me.

Acharya sings the song with perfect ease by letting the beauty of the language, rhythm and feelings imbue the lyrics and work in perfect unison. His rhythms are smooth and natural. Acharya’s voice perfectly expresses these subtle changing moods in the song. I can take the example of several outstanding Nepali songs and other musicians’ music, but not many. The poet told me that Acharya had addressed the feelings of a poet or a listener with total honesty in this music and singing. We should not forget to appreciate the consonance of words, music and singing in Acharya’s oeuvre. Sadly, the musical channels do not mention the names of the poets and, in several cases, the names of the musicians.

We find original patterns of music writing and singing in Acharya’s other songs, especially in those composed around the theme of human relationships. The originality of the musician and singer lies in the treatment of the songs they select. We can see certain conspicuous features of Acharya’s musical taste and choice in his singing, particularly in songs like “Jati Chot Dinchhau”, “Mutu Jalirahechha”, “Jahan Chhan Buddha Kaa Aankha”, “Maya Meri Sanjha”. His music shares some essential features of the time. The range of his singing from sugam and choir to bhajan was remarkable.

We should remember that Acharya maintained his continuity through meaningful silence since 1989, like a rishi. That became possible also because of the musical continuity of his two talented sons, Satya Raj Acharya and Swaroop Raj Acharya, known as the Satya-Swaroop duo. The overwhelming tribute paid to him by people shows the power of Acharya’s music, which has continued to create reverberations in their minds. My tributes to the musician and singer Acharya.

24.32°C Kathmandu

24.32°C Kathmandu