Columns

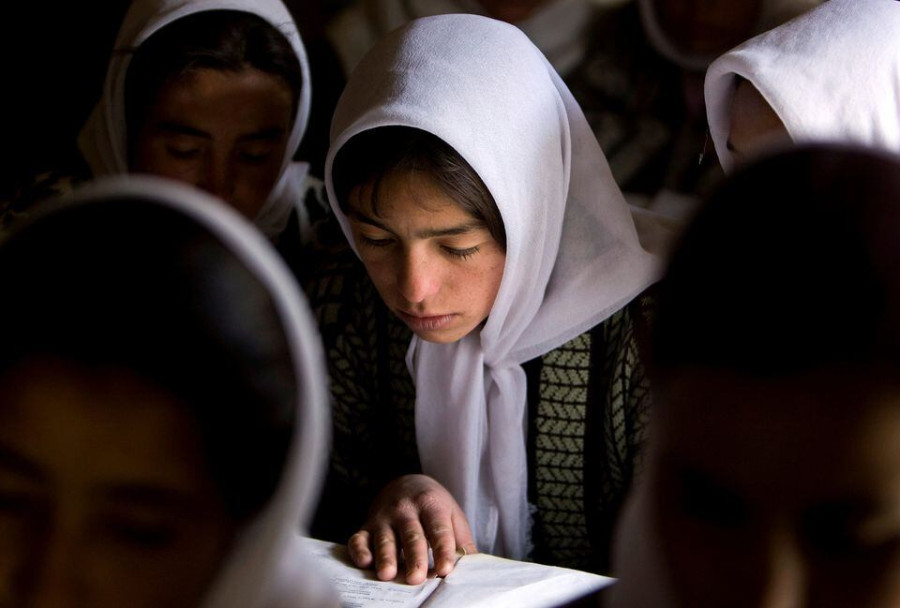

Fight to educate Afghan girls

Afghanistan is the only country where girls are prohibited from attending school beyond the age of eleven.

Yasmine Sherif & Gordon Brown

It has now been over two years since the United States military ended its decades-long war in Afghanistan, and the world’s attention has predictably shifted to the horrific conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine. But the mess left behind by the chaotic US withdrawal has not been cleaned up—far from it. Since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, the country’s economic and humanitarian crises have deepened and sharpened.

Conditions for Afghan girls and women, in particular, have deteriorated rapidly, shattering their hopes for their personal and professional lives. In edict after edict, the new theocratic government has systematically stripped them of their fundamental human rights, including to an education. As a result, Afghanistan has become the only country in the world where girls are prohibited from attending school beyond the age of 11.

Millions of Afghan girls are being denied a chance to develop their talents and fulfil their dreams, putting a generation at risk of lasting damage and jeopardising the country’s economic future. Worse, those girls and women who fled to Pakistan to continue their education will once again be denied schooling. The Pakistani government recently ordered the expulsion of 1.7 million undocumented Afghans, around 700,000 of whom sought refuge in the country after the Taliban’s takeover.

But the Taliban is not a monolith: Some government officials seemingly recognise the critical importance of their daughters returning to school. In November, Rangina Hamidi, an education minister before the Taliban’s return to power who had just visited Afghanistan, suggested that the Taliban could be convinced to reopen girls’ secondary schools.

For that to happen, however, the international community would need to engage much more actively with the Taliban, and help its more moderate voices prevail over the hardliners. Hamidi’s experience, and that of others, suggests that there are increasingly apparent internal divisions within the Taliban regime over the education of girls and women.

In this context, Muslim-led delegations should visit Afghanistan and meet with both the Taliban’s formal governing cabinet in Kabul and its leadership council—comprising religious leaders—in Kandahar. The aim would be to open lines of communication and express support for reversing the ban on girls’ education.

The dire situation in Afghanistan demands urgent action. Even before the Taliban regained power, the country was one of the world’s poorest and most underdeveloped. Now, more than two years into Taliban rule, the economy has all but collapsed, and millions of Afghans don’t know where their next meal will come from. The United Nations World Food Program has warned that acute malnutrition is above emergency thresholds in 25 of 34 provinces and is expected to worsen. Moreover, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated that two-thirds of Afghanistan’s population—a staggering 28.3 million people—would need urgent humanitarian assistance to survive this year, owing to long-term drought-like conditions and crippling economic decline.

Despite these stark figures, the Taliban’s religious leadership has continued to hack away at the rights of girls and women, often to the exclusion of other policy objectives. This systematic discrimination includes not only denying girls and women access to secondary and tertiary education, but also restricting their freedom of movement, expression, and association and prohibiting them from almost all forms of employment.

The participation of women in public life is heavily constrained, as they often cannot leave their homes without a maharam (male relative). Moreover, the Taliban has effectively removed any possibility for women to seek justice through the judicial system. After UN experts visited Afghanistan earlier this year, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) concluded in a report that the Taliban’s discriminatory and misogynistic policies and harsh enforcement methods constitute “gender persecution and an institutionalised framework of gender apartheid.” Richard Bennett, the OHCHR Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Afghanistan, described it as a “crime against humanity.”

Diplomatic recognition of the Taliban government, let alone fully normalised relations, is certainly out of the question as long as religious edicts deprive girls and women of their basic human rights. But that does not preclude the international community from taking steps to promote gender equality.

One such step would be developing new channels of communication—possibly though Qatar or the United Arab Emirates—with Taliban officials who understand that Afghanistan needs to educate all young people. The internal divisions within the regime have opened a window, albeit a small one. We must seize this chance to help give the world’s most oppressed girls and women the opportunity to realise their potential.

Brown, a former prime minister of the United Kingdom, is the UN Special Envoy for Global Education and Chair of Education Cannot Wait, and Sherif is the executive director of Education Cannot Wait.

—Project Syndicate

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu