Columns

Behind the euphoria of higher remittance

Had it not been for migrant workers, life would have been tough like in countries with low foreign currency reserves.

Deepak Thapa

For some time now, one piece of news on the migration front has been a steady drumbeat about the increasing remittances sent home by Nepali workers from around the world. In the last fiscal year alone, Nepal received a record of nearly $10 billion. A direct impact of this happy state of affairs has been on our foreign currency reserves. At last count, it stood at $10.8 billion, not quite the all-time high of $11.3 billion achieved in early 2021 but getting there. Most importantly, we have managed to avoid the fate of two of our neighbours, the much larger and richer Pakistan and the still wealthy but currently hapless Sri Lanka, both struggling with depleted foreign exchange reserves.

There is no doubt where credit for this has to go—the hundreds of thousands of our compatriots working across the globe. Such has been their contribution to the nation’s economy over the decades, but it requires reminding time and again so that we can all collectively thank them—in thought at least.

Keeping the nation afloat

One does recall how pleasantly surprised everyone was to learn that the incidence of national poverty had actually declined from 42 percent in 1995-96 to 31 percent in 2003-04, years coinciding with the height of the Maoist conflict and economic activity taking a big hit. The poverty rate declined further to 25 percent in 2010-11, a period of comparable social and political upheaval.

As an Asian Development Bank report from 2013 noted, among the ‘factors that have had the most significant impact on reducing…poverty incidence, intensity and severity and have contributed to human development indicators’, the highest honour was due to the ‘increase in remittance’. Further, it said the ‘[c]ontribution of remittances has been a key factor in increasing per capita income and poverty alleviation’ and had ‘helped maintain macroeconomic stability during the conflict era…’.

We can expect to learn that poverty has declined further once the latest round of the Nepal Living Standards Survey (NLSS) results are published. In the period since the NLSS of 2010-11 and 2022-23, when the last one was conducted, remittance inflow has gone up exponentially. That international remittances have equalled around a quarter of the national GDP is old hat by now, but it is the actual volume that is astounding: from Rs 0.55 billion in 1990-91 to Rs 9.8 billion in 2000-01, Rs 225.9 billion in 2010-11 and Rs 841.5 billion in 2021-21.

Facilitating elite migration

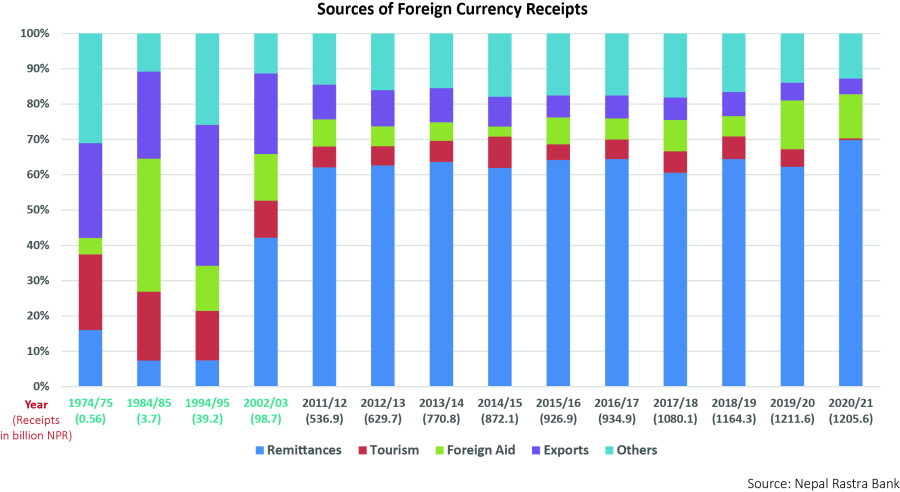

With exports remaining stagnant and the foreign investment scenario even more pitiful, remittances are also by far the most significant source of foreign exchange for Nepal. In fact, that has been the case since 2002-03, when earnings sent home by Nepalis edged out exports, tourism and foreign aid to grab the top spot. Over the years, that position has only become unassailable, and remained so even through the Covid-19 years.

That leads one to the unhappy conclusion that had it not been for migrant workers, life in Nepal would have been as tough as it is in many countries with foreign currency reserves running low. Sri Lanka is only the most extreme example and Pakistan has been in the news lately for the same reason. But countries as afar as Bolivia, Lebanon and Kyrgyzstan are in the same boat and there are many others ready to trip up. We ourselves experienced a taste of what a stricter foreign currency control regime looks like when the government restricted the import of a number of items, ranging from motor vehicles to playing cards and tobacco, for seven months in 2022.

What is little commented on is the link between the cushion provided by increased foreign exchange earnings through remittances and the outmigration of students. We do not have very reliable government figures on student migration. The best we can do is look at the ‘no-objection certificate’ (NOC) numbers. Accordingly, there were more than 100,000 students who received NOCs to study in a third country last year, a figure that represents a quadrupling of NOC recipients over the last decade. These students sent out $750 million of the country’s precious foreign currency to finance their education.

One wonders what our monetary policy vis-à-vis NOCs would have been had our foreign exchange reserves been in dire straits. As a corollary, one cannot help but note that those toiling in the Arabian sands and the sweltering factories of Malaysia are making it possible for the upper and middle classes to send their kids abroad. Their departure is often accompanied with a parental decree to build a life for themselves away from Nepal even as those who make their migration possible can only hope they make it back home unscathed.

Some concern has been expressed about the ongoing trend of students leaving Nepal, and Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal also weighed in recently. “Student outmigration is not only leading to the exodus of youth human resources, but the country’s wealth is also leaving with them”, he said.

Dahal's solution was an obvious one: Improve the education system in Nepal to retain students back home. He went one step further to say that were that to be achieved it would be possible to attract foreign students and reverse the drain on our reserves. He then took on a realistic tone and said such a transformation is not possible overnight and requires carefully planning, etc, etc. Having steadfastly refused to introduce any kind of reforms in either in school or university education and continued to encourage politicisation of the sector, such words are just what they are—worthless platitudes.

Hopes and haplessness

Meanwhile, we get stories like this one published in onlinekhabar.com with the eye-catching headline: ‘Around 600 have entered America, another 600 are en route, and many more are getting ready to leave’. Those were the words of the chairperson of Banphikot Rural Municipality in Western Rukum district on how entire villages have been caught up in the dream of making it to the United States.

Pradip Khatri was among those with such aspirations. His father, Bagbir, took out Rs 5.5 million in loans to send Pradip with human smugglers. He learnt a year later that Pradip had died in a boat accident. With interest, the loans had swelled to Rs 10 million. Seeking to recompense Bagbir, the agent offered to take his second son for free. The headline for Bagbir’s story read: ‘One son died in the jungle of Panama, another is on his way.’

Reports such as this from the erstwhile Maoist ‘base area’ serve as a telling indictment of Prachanda, and his band of Maoists. Do they care though?

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu