Columns

A climate reality check

We need to begin addressing disasters by developing small and affordable measures.

Madhukar Upadhya

This year's monsoon wasn't as destructive as expected in its first few months. In the beginning of October, however, it got unexpectedly worse, especially in the western part of the country causing widespread landslides and floods that killed 70 persons, inundated huge swathes of rice fields, and damaged about 1,500 houses. More than 30,000 people have been displaced so far. What has become apparent is that the destruction caused by water-induced disasters has been increasing in unprecedented ways for the last few years. The 27th Conference of the Parties (COP) is going to be held in Egypt in a few weeks from now. Loss and Damage (L&D) will be high on the agenda for the least developed countries, but the likelihood of getting it funded remains low.

Climate negotiations, after the Paris Agreement, focused on two major issues–emissions reduction and climate finance. Emissions reduction primarily requires industrialised nations to cut emissions with urgency. This change would mean shifting from fossil fuels to clean energy which may compromise economic growth during the transition. However, it seems that the big emitters aren’t ready to take meaningful action. The aim to put off the average global temperature reaching 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels to 2030 is quickly becoming a pipe dream. Experts argue that if the current rate of emissions continues, we might experience that threshold within the next five years. The ferocity of disasters that we've witnessed across the world lately is the result of temperatures increasing by only 1.1 degrees Celsius. Should the rise reach 1.5 degrees Celsius, the scale and scope of disasters will balloon faster than we could comprehend.

Financing front

On the financing front, climate projects for adaptation in vulnerable countries have already been delayed by lack of funds. Now, climate impacts seem to have surpassed adaptation goals. Therefore, support for rebuilding livelihoods and reconstruction of damaged infrastructure in the event of disasters has become a priority for vulnerable countries. It will require billions of dollars, a sum which will keep industrialised countries from accepting the proposal of funding L&D. So far, Scotland and Denmark have contributed $15.2 million followed by some philanthropists, and the government of Wallonia (Belgium) adding another $3.9 million. Sadly, other wealthy nations haven’t shown the same initiative. Instead, United States climate envoy John Kerry has been quite vocal regarding the proposal saying no country has trillions of dollars to spare to fund L&D implying that it isn't a priority for the industrialised world.

Meanwhile, along with increasing emissions, the volume of the global economy exploded in the 21st century. Unfortunately, it's concentrated in the hands of a few companies and individuals. The World Inequality Report 2022 reveals that the top 1 percent of the global population owns 38 percent of the world’s wealth and 19 percent of all income, while the bottom 50 percent owns only 2 percent of global wealth and around 8.5 percent of the income. The rich have the capacity to influence governments to formulate policies to safeguard their interests: To continue with business as usual regarding the fossil fuel industry. A glaring and stinging example is the United Kingdom’s recent announcement to issue more than 100 new oil and gas licences to meet its domestic energy needs.

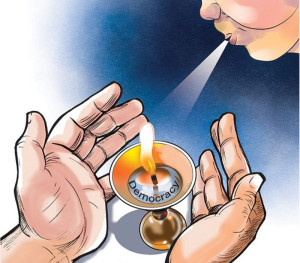

Like it or not, we've already entered a new world of climate realities, which will become increasingly more volatile than we're used to. The cropping season might change. The water cycle at the local level might be disrupted. Disasters caused by higher temperatures and increased intensity of precipitation will continue to plague us. The ongoing lengthy process of negotiations to push for emissions reductions and addressing L&D will continue at global fora while vulnerable nations suffer.

With mounting climate threats, Nepal desperately needs to ensure the safety of its citizens and continue to meet development needs with the available resources. We must realise that the damage caused by floods, landslides and droughts isn't new. We've suffered these losses every monsoon for decades. Perhaps, part of the answer to our problem of protecting our interests while addressing climate-related risks lies in our past experience.

In the late 1950s, our first state-led response to floods and landslides was to relocate the victims from the hills to the plains. Since then, we've failed to build on that response and go beyond it to develop ways to reduce the risk of floods and landslides. Now, both the frequency and scale of disasters will continue to increase, making us even more vulnerable to these hazards and their resulting damage. Bangladesh, a country intimately familiar with the devastating impacts of annual floods, has now developed innovative measures, adopted new polices, and established institutions to reduce flood risks. It has made flood management an indispensable component of its poverty reduction strategy. Now, the South Asian nation has the experience to teach other countries how to manage floods.

Recognising local potential

We need to begin addressing disasters by developing small and affordable measures suitable to our economy so that people at the community level can also use them to reduce climate-induced risks. This would mean developing technical, administrative and economic capacity at the local level. We're already allocating over 5 percent of our public budget annually to implement climate-relevant activities. There's a need to examine how effective this funding has been in reducing vulnerability or enhancing resilience of communities to climate stresses. That done, we need to ensure that each development sector has a clear understanding of how it's affected by climate stresses, and how it can work with other related sectors for synergy in order to make its investments climate responsive.

With the formation of local governments with a constitutional mandate to manage natural resources and tackle local environmental hazards, it should be rather easy for local leaders to identify what can be done to reduce risks at the local level. They're well-placed at the interface of traditional ways and high science to forecast weather events in a warmer world. The key is to recognise local potential to marry these two and help communities take advantage of it.

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu