Columns

Maoist castaways

The party and its leadership have moved on to mundane pursuits like power and money.

Deepak Thapa

The subject of this piece is somewhat dated, but since it is one that had affected me somewhat deeply, and as it is also one that defies temporality, I have decided to present it nonetheless. I am referring to Prakash Saput’s music video, “Pir”, which unleashed a furore of sorts when released a few months ago.

Taking a stand

In a sign of growing assertion after the 1990 political change, different social groups began taking issue with how their communities have been presented in popular culture. Among the first such instance was the row in the mid-1990s raked up by some in the Kirat community who were none too happy with Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala’s novel, Sumnima (1969), and its characterisation of the eponymous Kirat protagonist. Then there was the controversy over singer Kumar Basnet’s song “Dalli Magarni”, which by its very connotation was denigrating of the vertically challenged and equally so of Magars.

Basnet’s most famous song is arguably “Kathmandu ki Newarni”, in which he extols the beauty of women of some select ethnicities. In his defence, one can argue that he was simply lauding their comeliness. Yet, it is hard to deny that by simply referring to them in his opening and closing lines in a song about unrequited love, he manages to “other” them. Not to mention how he also succeeds in sexualising women from communities not his own.

One now cringes at the lyrics to those songs and many others we grew up listening to and humming along with many of these now-objectionable tunes since we simply believed that was the norm. Just some years later, we realised how wrong we were, and that just because it was okay at some point in time does not mean it should be acceptable forever. Stereotypical portrayals continue even today, but thankfully growing rarer over time. And when it does happen, there is a strong enough constituency that calls out the creator to ensure some kind of correction.

Toe the line

Disrespect toward entire groups of people, whether identified in terms of gender, caste/ethnicity, language, or religion, in artistic or any other expression is despicable and needs to be condemned. But such outrage can hardly be justified when it comes to speech in general, as in the case of Saput’s video.

That songs are a powerful way to capture the imagination of the public is well established. The Nepali communist ballad, “Gaun, gaun bata utha”, that aimed to rouse people to revolt against the status quo was used most effectively by the party that has now become the UML. Perhaps that explains why the same folks were so incensed to the point of violence a few years ago when singer Pashupati Sharma came up with his catchy “Lootna sakay loot kanchha”, a satire on how the state coffers were beginning to serve as the ruling elite’s personal account. The powers that be did not quite appreciate a commonplace sentiment being put to music, and unleashed their minions to force poor Sharma into taking down the song from his YouTube channel.

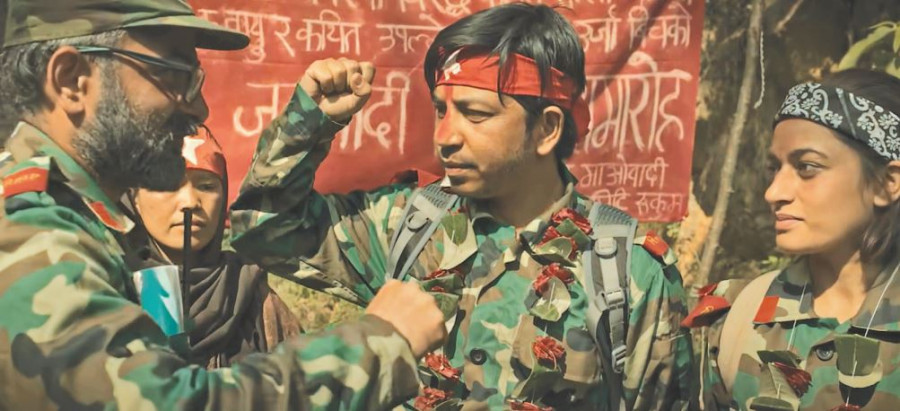

The story in Saput’s song is similarly not uncommon. It details the daily struggles of a husband-and-wife couple Maoist fighters in post-2006 Nepal while juxtaposing it against a leadership who continue to reap the benefits of the sacrifices of their cadre. The song was roundly condemned by the Maoists. A section of the latter even charged Saput with having outdone “reactionary political forces who are now trying to present themselves as advocates of a federal, democratic republic”. The singer was warned to take down the video and issue an apology. That, he duly did, but as the rest of us know, the only mistake he made was to show the reality of what has happened to the vast majority of those who put their lives on the line for the sake of a New Nepal.

As someone who tears up at even the most melodramatic scenes in Hindi films, it was natural for the video to evoke strong emotions in me. It was not the melodrama though that moved me. Rather, it was the memories of having met or read about those like the male protagonist in the video, a battle-hardened Maoist who still believes in the word despite the circumstances he finds himself in.

The forgotten

One that I remember well is Kesh Bahadur Batha Magar. He headed the Rolpa committee of the breakaway Mohan Baidya-led CPN (Maoist) when I met him in 2014. After denouncing the path taken by his erstwhile comrades and having tried to convince us that Baidya’s line was true Maoism, he started talking about his personal life. It turned out both his sons had taken part in the “People’s War”. At the time of our meeting, one was in Qatar while the second had similar aspirations but could not qualify because he had lost an eye in battle. He was struggling as a security guard somewhere in Kathmandu.

Hemanta Prakash Oli was in the news not so long ago quite recently as a top leader of Netra Bikram Chand’s faction of the Maoists (from which he has since been ejected). In an interview, he mentions how, when he was with the Prachanda Maoists, following the collective decision of doing away with private property, he handed over all he owned to the party. “There was a proposal [within the party] to proletarianise. Believing that to be truly the case, I gave everything. Others did not. I have nothing to my name now.”

Given that Oli’s erstwhile boss, Prachanda, is building a house for himself in Chitwan, I can bet he was among those who did not give all to the cause he himself was leading. Whether one agrees with Oli or not, everyday reminders such as this must be quite a letdown to the aspirations held by thousands for the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Take also the example of Laxmi Pun, an underground reporter for the Maoists. She once told me that due to her Indian education, her English was good and she was much valued in her party during the insurgency. She has written about an incident that foreshadowed Saput’s song by many years. Waiting at the gate of Prachanda’s then residence at Lazimpat, she was with a former guerrilla couple and their daughter. Upon being suddenly informed that there would be no further meetings that day, the wife started crying. One can only imagine with what high hopes they had hoped for an audience with their supremo. Just then a sleek car carrying a rich woman politician—who was not a Maoist—arrived. The gates swung opened and shut, leaving out those on whose backs Prachanda had vaulted himself to power.

There is this one scene from Saput’s video that stayed with me for long. When the male character drops off his wife at the airport on her way to “Arab”, just before they part, they exchange a furtive, albeit tentative, lal salaam. Despite the raw deal they have received, this couple has not given up on the human instinct for justice. I wonder how many continue to delude themselves with that hope even as the party and its leadership have long moved on to more mundane pursuits like power and money.

21.18°C Kathmandu

21.18°C Kathmandu