Columns

The Afghan tragedy

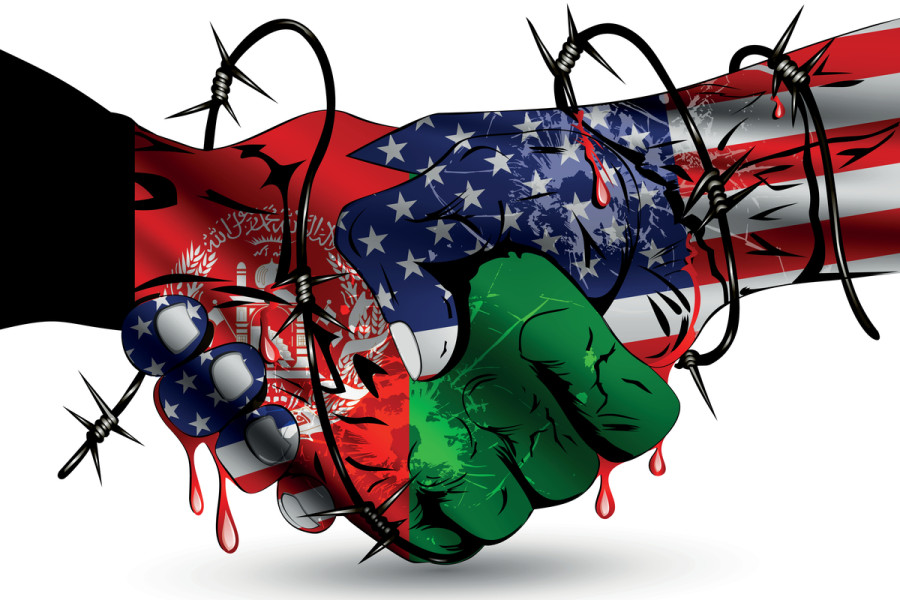

Afghanistan’s chaos stems from American hubris and a military-industrial complex that thrives on war.

Amish Raj Mulmi

I remember watching one of the planes crash into the World Trade Centre on a hazy television set in our hostel common room that day in September 2001. For such a momentous event, I have few other memories of that day, except ephemeral flashes: Plumes of smoke rising in the clear blue skies of New York. Chaos and dust on the streets. And a group of 12th-grade boys sitting in faraway Dehradun, trying to figure out what on earth was happening out there.

Twenty years later, we now know 9/11 was the day that changed everything, at least for our generation. When George Bush Jr announced, "Either you are with us or against us," we should have known liberty and freedom went hand in hand with military contracts, KFC and Big Macs, and CIA black sites. Twenty years later, as the United States leaves Afghanistan in a shambles, how many of us remember the climate of fear and paranoia in the aftermath of 9/11? And the dire warnings about the "clash of civilisations" that was doomed to occur, because only the West believed in individual freedom while the East didn’t? And the narrative of a war between good and evil? As Arundhati Roy wrote in her brutally prescient essay on the eve of the US invasion of Afghanistan, ‘How many dead Iraqis will it take to make the world a better place? How many dead Afghans for every dead American? How many dead women and children for every dead man? How many dead mojahedin for each dead investment banker?’

Whether freedom has endured and justice has been infinite, we will learn in the coming days, as the US media machinery creates a counter-narrative that will portray its 20-year occupation as a victory. Perhaps a few Hollywood films will tell us about the bravery of American soldiers in these last days (hopefully, the two men who fell off the military aircraft’s wheels will also be portrayed). But what we know now is that by invading Afghanistan and Iraq, the latter on falsehoods, the US began to spiral down a path that brought the world closer to Osama bin Laden’s fanaticism.

When the history of these two wars will be written, let it not be forgotten that Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib existed despite American claims of justice and human rights and that private mercenary armies like Blackwater (renamed twice for better PR since its soldiers massacred 14 civilians in Baghdad in 2007) became part of the American establishment. But it was not so different even in 2001 when American vice-president Dick Cheney’s links to the military contractor Halliburton were known. Americans chose to gloss this over, for they were too hungry for revenge. "This new enemy seeks to destroy our freedom and impose its views," Bush Jr had said in November 2001. Twenty years later, it’s clear the US of today—post- Trump, post the white Christian supremacists, post the Capitol Hill attack—resembles the very enemy it once attacked.

And let us not forget the white saviour complex about bringing democracy to a war-torn land. Though US President Joe Biden may deny the US was in Afghanistan for "nation-building", his predecessors certainly didn’t. The US "pledges its full support as Afghans continue to build the institutions of democracy. America will launch an ambitious training programme for newly-elected Afghan politicians and help newly-elected assembly members better serve those who elected them... We're helping to build the new Afghan national army and to train new Afghan police and border patrol", Bush Jr had said in June 2004. If the US wasn’t in Afghanistan for nation-building, it was undoubtedly the biggest warlord in a country full of warlords. And now that the collapse came quicker than it expected, the spotlight has been turned on how poorly trained the Afghan army was, how corrupt its ranks were, how poorly motivated they were, and how the collapse was "years in the making". Essentially, it’s anybody’s fault but the Americans.

Let’s also not forget that it was not just the US that went into Afghanistan, but a host of other countries. These countries were the first to evacuate their citizens and then denied their Afghan counterparts the same facilities. Some, like Sweden and the Netherlands, are said to lead the world in the human rights discourse; some, like France, will "protect itself from a wave of migrants" from Afghanistan. These are the nations whose "humanitarian missions" are lauded in countries labelled as the third world or developing. Now that we know they will leave us behind in a crisis, how can we trust them?

In the days to come, there will be thousands of op-eds and reports on the Afghan war, on the "inevitable" collapse after the withdrawal, on Afghan women under the Taliban, and on the "graveyard of empires" that Afghanistan is supposed to be. Their newspaper editorials will call it the "tragedy of Afghanistan" and lament the erosion of the American dream—"of being the ‘indispensable nation’ in shaping a world where the values of civil rights, women’s empowerment and religious tolerance rule.” But few will have it in them to point fingers where it really matters: the military-industrial complex and its intractable hold over the American establishment. As we’ve learnt in the past two decades, wars begin with lies. And surely, there will be more lies in the future, for the war industry needs something to feed off.

The US invasion of Afghanistan has been labelled futile by many, but the nearly $2 trillion spent on the war tells us it really wasn’t futile by any standard. Whether it was corruption or whether it was funnelled to the military effort, the money has made its way to someone’s pocket. Careers have been made, and fortunes built from this war. Further, nearly $19 billion was lost to "waste, abuse and fraud" between 2009-19 by the US government’s own admission. Such a gargantuan loss, and it remains an accounting footnote.

Twenty years to the day, everything changed, the US has left Afghanistan with "[n]ot one benefit, political or military… Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated", as a reverend wrote in the aftermath of the First Afghan War in 1842. Once again, the focus has remained on the retreating power. As for Afghanistan and its people, they will be newsworthy only until the next crisis, a tragedy unfolding on social media in real-time. After all, some countries will always be more equal than others.

5.81°C Kathmandu

5.81°C Kathmandu