Columns

Whatever happened to equity and inclusion?

That one group should progress so disproportionately talks about the failure of the state-society compact of post-2006 Nepal.

Deepak Thapa

‘The best constitution in the world’ were the words used to describe the 1990 constitution. In the fog of time, I can be forgiven for a lapse in memory but I believe they were uttered by Daman Nath Dhungana, one of the drafters of the said document and the first speaker of the House of Representatives under it. Regardless of who is given (dis)credit for that somewhat fatuous assertion, we all know that was what the constitution was touted at the time.

Of course, no one had gone around poring over constitutions from around the world with a list of quantifiable indicators to measure where on a scale of ‘bestness’ each constitution lay. The claim to superlativeness was after all only an emotional outburst of relief. Emerging from nearly a century and a half of autocratic rule by the Ranas and then the Shahs, punctuated by a 10-year chaotic free-for-all period, it was enough that we had a constitution that more than passed muster as a democratic one, and people went all out in extolling it.

Although not much publicised, those drafting the 1990 constitution were more than aware that they had failed quite spectacularly in meeting the expectations of those who wanted structural changes that went much deeper into the nature of both the Nepali state and Nepali society. The politician-activist, Padma Ratna Tuladhar, who later played Tweedledum to Dhungana’s Tweedledee as peacemakers, is cited by legal scholar Mara Malagodi as saying that ‘the constitution was supposed to reflect the aspirations of the people, those aspirations raised by People’s Movement’. But it did not. As Malagodi concludes: ‘The question was how prepared were the Nepali political leaders to do away with ideological narratives established by thirty years of Panchayat regime.’

As we found out, not at all. Subhash Chandra Nembang, who headed both Constituent Assembly I and II, recalls that the feeling at the time was ‘no amendments to this constitution was necessary for the next 60 years. But with time some calls for reform were made. Eventually, it was abolished by the people’. And replaced in 2007 by a constitution that attempted to do precisely what the 1990 version had not—introduce a new national narrative based on the idea of equality for all. Together with the substantive amendments made following various social movements, the Interim Constitution can be considered a fair representation of, to borrow Tuladhar’s words, the aspirations raised by the Second People’s Movement.

Nembang presided over a process that finally gave us the present constitution after nearly a decade of uncertainty, and which once again was propelled immediately to the status of ‘best constitution’. He explicates: ‘This constitution is important for two reasons. First, the constitution was written by the representatives of the sovereign people…Second, the constituent assembly that made the constitution was inclusive in every way... the constitution was written by an inclusive CA through a participatory process. We made attempts to reach a broader political consensus by holding extensive discussions throughout the course of constitution writing. This enabled us to produce a constitution based on the principles of federal democratic republicanism, secularism and inclusiveness.’

There is no quibbling that both editions of the constituent assembly were highly inclusive by far. That is as far as we can agree with Nembang though. The bulk of the constitution may have been written ‘through a participatory process’ since there would be little disagreement on issues such as universally accepted fundamental rights, or, by that time, the need for affirmative action for the marginalised. But we also remember very well that crucial decisions were the least participatory, as that infamous spectacle back in May 2012, just before the dissolution of the first constituent assembly, when the honourable members were forced to sit around twiddling their thumbs even as the cabal of top leaders peremptorily decided on everyone’s behalf what the way forward would be.

The same absence of a ‘participatory process’ was repeated in the second constituent assembly as well with our elected representatives reduced to simply rubber-stamping whatever was decided by that exclusive group. But that was between the party faithful and their leaders and if that is how they wanted to roll, who are we to object? Objections certainly can be raised when we are repeatedly told to believe the fiction that the constituent assembly was a deliberative body and that the constitution is a document par excellence because it came out of an inclusive process.

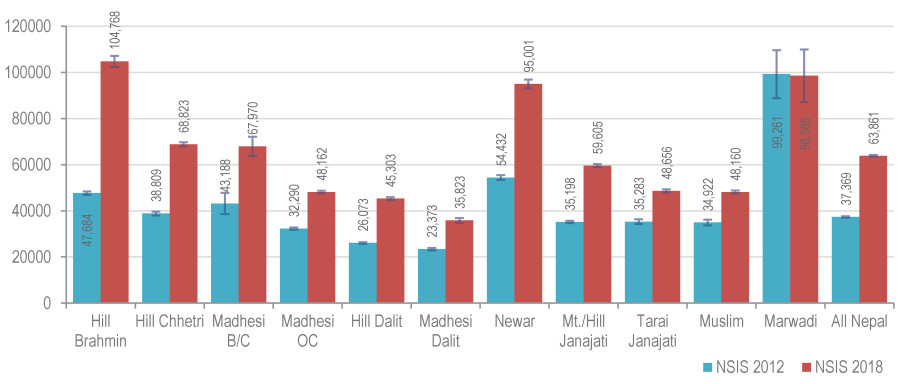

Another stalwart of the ‘best constitution’ brigade is Krishna Prasad Sitaula. A key member of that male-only club that decided our fate in 2015, it was Sitaula who is said to have been responsible for inserting that unnecessary clause that defined ‘secularism’ in our context; and succeeded in undermining the very essence of secularism itself. Although politically from the other side of the aisle as Nembang, Sitaula, too, is of the view that our constitution has managed to resolve the problems of exclusion. It is due to this absolute conviction about the power of the constitution to magically create an egalitarian society without constantly striving to tackle the multifarious sources of inequity that forces one to ask people like Sitaula and Nembang how they would explain the accompanying figure.

The graph has been taken from the publication State of Social Inclusion in Nepal, one that seems to have attracted little attention despite its extreme relevance. It was produced by the Department of Anthropology at Tribhuvan University, our premier centre of higher learning, and hence not easy to brush aside as some ‘NGO publication’ as is the government’s wont when faced with uncomfortable evidence. The report uses data from the Nepal Social Inclusion Survey conducted by the Department in 2012 and 2018 to show how household consumption patterns—as in expenditures on food, education, agriculture inputs, medicines, clothes, utilities, etc—had changed over that period among the country’s various population clusters. We see that in aggregate Hill Bahuns have more than doubled their family expenses, far in excess of any other group. While one can take heart in the fact that there were none that remained stagnant or, worse, regressed, that one group should move ahead so disproportionately certainly points to the failure of the new state-society compact supposedly heralded by post-2006 Nepal.

Even if we accept the argument that the constitution is a very inclusive one—and it is, to a large extent—there certainly seem to be other forces at work aiming to undo its promises. It takes a lifetime and more of dedication to ensure that the fruits of an inclusive democracy are shared by all. The likes of Sitaula and Nembang, and of Oli, Deuba, Nepal, Dahal, Poudel and Khanal, appear to believe that with their having delivered the constitution, with all its nods to inclusion, there is no need to dwell further on the matter. That certainly is not a formula for a stable and conflict-free future for Nepal.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu