Columns

Nepali language at SOAS

It is a shame that the language has lost one of its oldest homes in the West.

Deepak Thapa

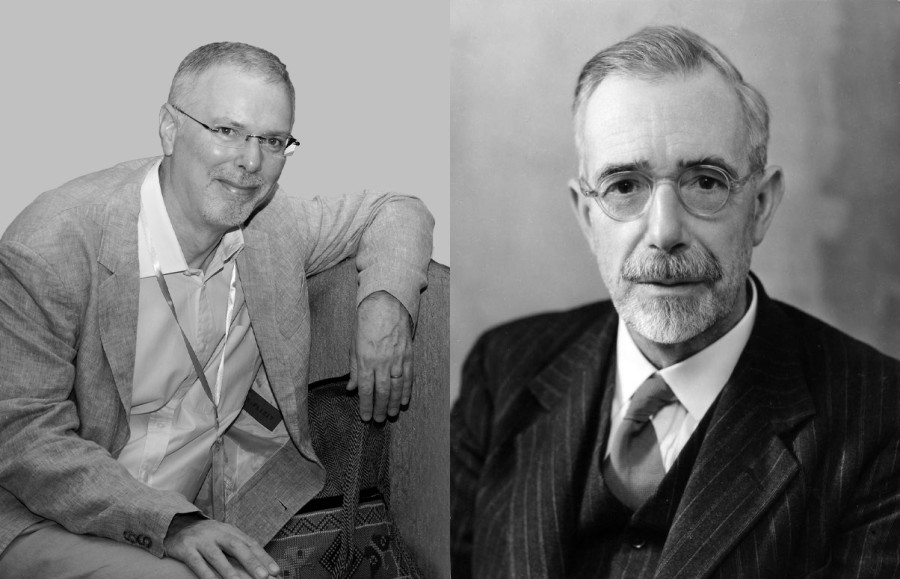

‘Bravest of the brave, most generous of the generous, never had country more faithful friends than you’. These are words anyone interested in the Gurkhas is sure to come by, sooner rather than later. They featured in the preface to Ralph L Turner’s A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language, the monumental tome that still serves as a most useful Nepali-to-English reference almost a century after it was first published. Turner, a ‘sometime’ officer with the Gurkha Rifles, was paying tribute to the men he had served with during World War I. Turner earned his name, of course, more as an academic than a warrior, having spent almost his entire career at the School of Oriental and African Studies.

Starting with Turner in the 1920s, the institution now known simply as SOAS University of London had always had strong links with Nepal and the Himalayan region, with the presence of renowned scholars such as Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf and David Snellgrove. And, until recently, it was the only institution of higher learning in the Western world where Nepali was part of a regular college course, with the possibility of taking the subject for a fourth of the credits required for an undergraduate degree.

Unfortunately, SOAS’s connection with Nepal has now seen what appears to be a definite rupture with Michael J Hutt, Professor of Nepali and Himalayan Studies, taking premature retirement a couple of months ago. The departure of Mike, as he is universally known, from the institution he was part of for more than 40 years, as a student and then a teacher, was partly a result of the demand for Nepali language classes having dissipated over the years. Mike believes that is due to the massive hike in tuition fees in British universities, with students now more likely to be attracted to courses they believe are likely to guarantee a job to pay off their student loans. It is a trend that has affected not only Nepali but many other languages as well, with the only South Asian languages currently on offer at SOAS being Hindi, Punjabi, Sanskrit and Urdu.

End of an era

In 2017, Mike had delivered a keynote address at Cornell University in New York in what in hindsight appears to have been the precursor to what actually came to pass at SOAS. The Cornell event was organised to coincide with the retirement of David Holmberg and Kathryn March, professors of anthropology. The husband-wife team had started the Nepali language summer school at Cornell which had become the first stop for many from North America who ended up coming to Nepal as part of their studies. The worry then was that with their exit, interest at Cornell in Nepal and the Nepali language could wane, and the gathering of academics working on Nepal was meant to showcase the yeoman service Holmberg and March had performed over the decades, with the hope that the programme would continue. That hope has not been belied and the Nepali language course is going strong in Cornell.

The irony is that an American university with no prior history with Nepal has continued with the language programme while a British institution with its long Nepal association decided to give it the axe. For all the talk of the special relationship between the two countries, with Turner’s words even inscribed beneath the statue of the Gurkha soldier standing smack in Whitehall, the seat of the British government, it was not thought expedient to continue the teaching of Nepali in the UK.

With Mike out of SOAS, however, it is not only Nepali language teaching that comes to an end but other activities will suffer as well. With its convenient location in London, SOAS has always been where many Nepal-related events in the UK—political, cultural, social and educational—have been hosted. The annual Britain-Nepal Academic Council lecture has been delivered there since its inception some 20 years ago. With its impressive lineage of Nepal scholars, SOAS had been the UK’s go-to place for expertise on Nepal and the Himalayas, as when the 2001 palace massacre took place and Mike was the most visible presence on BBC trying to explain the unprecedented nature of the killings to a global audience. Obviously, SOAS will still retain an interest in Nepal through its South Asia Institute, but it will not be the same as having someone we can call our own there.

It is a pity that even the substantial Nepali diaspora in the UK was unable to produce a few candidates with an interest in Nepali to help keep the programme alive. Equally a pity that there was no effort on the part of the Nepali state either to provide some sort of continuity. One would have expected the current government to be at the forefront staving off anything that sounds like an affront to Nepali nationhood. With the Nepali language being one of the most distinctive markers of Nepali nationalism, the cessation of its teaching certainly qualifies as one. Whether the British government were so inclined or not, it might have made sense for our own to fund the teaching of Nepali at SOAS to provide continuity with a century-long tradition.

Given how more than a few Nepalis are likely to view it as a matter of national pride that Nepali is taught in a university in the West, I am quite certain no one would begrudge some money spent towards that end. If an individual like Indian industrialist Ratan Tata could gift $50 million to a university, surely Nepal can afford around $5 million, which appears to be how much it would cost to endow a professorship and fund some student grants as well as encouragement. A country that could hand over $6 million to the Jhalanath Khanal Foundation, mainly for being named after a ruling party hotshot, could definitely spare something on that scale.

Lasting contribution

Even had such an arrangement been possible, it would have been too late for Mike. But it might yet have enabled someone else to build up an oeuvre as impressive and eclectic as his, which includes Himalayan Voices, an old classic that introduced many English readers to the world of Nepali literature; Unbecoming Citizens: Culture, Nationhood, and the Flight of Refugees from Bhutan, one that has made him persona non grata there; a biography of poet Bhupi Sherchan, which included English renderings of his work; a translation of Basai, the well-loved novella by Lil Bahadur Chettri; Teach Yourself Nepali (co-authored with Post columnist, Abhi Subedi) along with the edited volumes, Nepal in the Nineties and Himalayan People’s War: Nepal’s Maoist Rebellion.

Mike’s very first journal article was entitled ‘A Hero or a Traitor?: The Gurkha Soldier in Nepali Literature’. As a Brit, it was perhaps natural that he should be drawn to the Gurkhas but the sensibilities he demonstrated even so early were spot on. Having demonstrated how scathing leftist writers such as Sherchan and Parijat were in their estimation of Gurkhas, he writes: ‘One wonders whether the average lahure would recognise himself in these descriptions. It seems unlikely that the Gurungs and Magars of the central hills, or the Rais and Limbus of the east, perceive any conflict between their Nepali patriotism and the tradition of service in foreign armies which has become an unquestioned way of life in many of their mountain villages’.

In recent years, Mike’s contribution to Nepali language and literature was being increasingly appreciated in Nepal; almost every time he came over, he would be out collecting an award or being accorded some other honour. With more time now on his hands and a higher output expected, the accolades can only increase—and, rightly so.

22.12°C Kathmandu

22.12°C Kathmandu