Columns

No justice, no peace

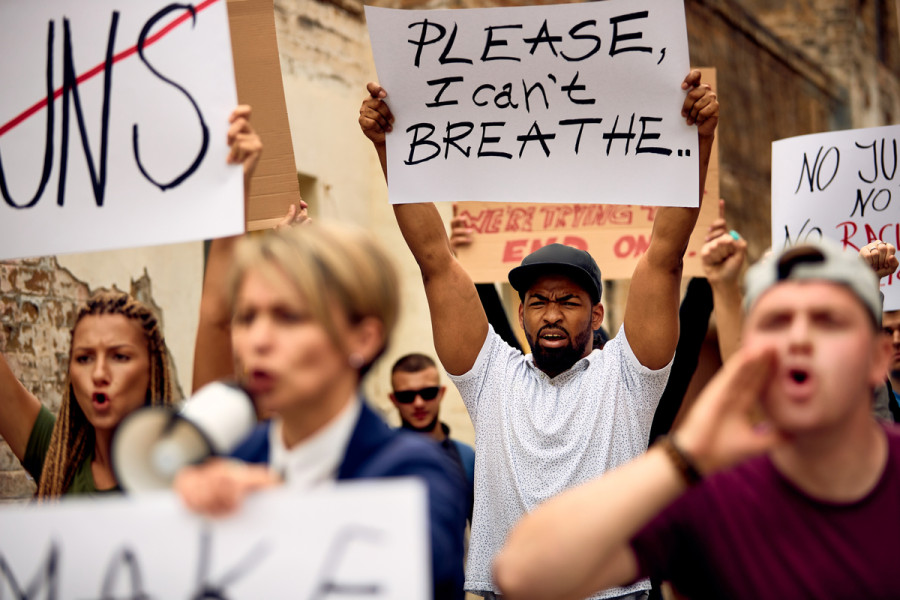

Young people are coming out for the very first time to protest against injustices. These newly minted activists may change the world profoundly.

Pramod Mishra

The world’s youths are in the streets, protesting. In the past weeks, since George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police on May 25, youths of every stripe have come out of their houses—with or without the consent of their parents—to protest racial injustices. London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, and more than 700 American cities, have seen the diverse set of protestors come out to face the police, who are often seen in combat gear. Slogans such as ‘I can’t breathe’, ‘Black Lives Matter’, ‘No justice, no peace’, are drawn upon banners.

What are the implications of such a global response to Floyd’s death? Do these demands for justice and feelings of suffocation evince new stirrings for a new future? Will these calls lead to a new political arrangement, new assertion for human conscience or even a new conscience? Has the conscience of the world awakened and arisen for the new century that has just come out of its teens? While a definitive answer to these questions would at best be speculative for now, one can safely say that there is a stirring of hope for a better future.

Every century, every epoch, and every time has had its own conscience that responds to the events of the day. It is not the first time that people, mostly young people, have dreamt big, led by their youthful zeal, and tried to create an ideal world. Most signatories to the Declaration of Independence and the American constitution were young idealists under the influence of the European Enlightenment. Equality, tolerance, reason, universalism, progress, separation from the asphyxiation of organised religion were some of the ideals they pursued, even though they could not realise them immediately.

Slavery, racial and gender ideas of superiority and inferiority and colonialism remained the biggest blotch to their ideals. From a postcolonial perspective, one can find fault aplenty in the Enlightenment because it applied in its time only to European men. Moreover, many of these ideals, such as reason, science and universalism sought to erase cultural relativism between Europeans and non-Europeans, imposing a one-size-fits-all, western ideal of progress and modernisation on the world, much of it under domination. Nonetheless, people in later generations would invoke those universalist principles to demand equality and freedom from all kinds of tyrannies, including colonialism.

The death of George Floyd has definitely shaken the conscience of the world, but it’s the youth that has the blood and the energy to descend on the streets and demand justice for the marginalised. In history, racial justice has been the most eluding. One can easily and safely become an environmentalist and decry the excesses of capitalism and industrialisation because all this does not require standing up for a group of people discriminated against for reasons of their skin colour or caste. This is not to say that advocacy for the earth is not important, only that standing up for a historically marginalised people requires more moral courage; because then one has to fight against community-sanctioned ideas and prejudices deeply held even by one’s own family members. To say all humans are equal, as the founding fathers of the United States did, is one thing but to demand its realisation in actual life requires moral courage, not just philosophical courage. That moral courage has come to the surface in young people today.

It is not that everyone from the dominant community lacked this moral courage in the past. Gandhi’s white comrades, among them such clergymen as CF Andrews and members of the aristocracy as Madeleine Slade, the daughter of a British Rear-Admiral, and many others that broke ranks with their own privileged class and stood together with the discriminated to fight the fight. It shows that injustice has a way to prick the conscience of many but stir a few into action among those who enjoyed the perks of privilege and power.

But the scale is different this time. Maybe it’s an indirect response to the rise of right-wing nationalist demagogues in many countries that the habitual voters holding deep-seated prejudices voted to power. So, it’s also generational self-assertion of the youth, trumpeting their arrival and heralding a new future. No matter what the concrete result of this diverse revolt, it sure feels good to be alive at this moment of sadness and hope.

What can one make of the revolt by the youth in Kathmandu and other cities in Nepal, which are not a response to either George Floyd’s death or the caste-related mass murder of six youth (four Dalits and two non-Dalits) on May 24? In the media, commentators have already pointed out this absence of race and caste angle to the recent revolt in Nepal.

While it’s important to point this justice angle out, the fact that the English-school educated children of the urban middle class have finally come out in the streets to face the police water cannons and batons says something about a possible generational change in Nepali politics as well. Nepali politics so far has been run by the anti-authoritarian fighter generation, who, in exile or prison or while underground fought to overcome the autocratic powers of the monarchy. The campus-generation of student activists, many of whom are now mid-ranking party politicians, have also exhausted their intellectual and electoral potential.

If exile, prison and insurgency were the traditional rites of passage for political leaders of the older generation, then street activism in the times of a pandemic could be another route for the youth. We don’t know if a new leader will be born out of this strife—we know very little of the protestors at the individual level—but the English-school educated generation surely will have an easy time, ideologically, to come to terms with the problem of caste and ethnicity. They certainly will approach it better than the older generation of politicians did, with their patronising attitude and self-centred politics.

If Nepal’s present constitution is the product of the older generation of politicians, the door is open now with this generation of youths for new possibilities—even though their consciousness level may not be fully informed of the complexities of Nepal’s ground realities. Let’s give them some time and educate them wherever possible.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu