Columns

Quake in Nepali history

When the earth shook in 2015, the politicians were suitably rattled to conclude they should promulgate the constitution.

Abhi Subedi

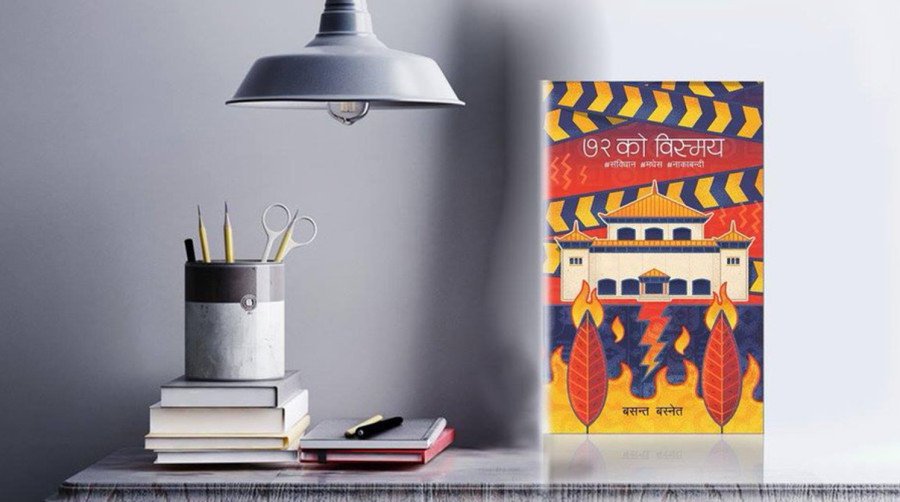

Browsing through the books queued up on my cluttered desk, the book 72 ko Vismaya caught my attention. The title, if translated into English, would read Dismay of 2015. Right below the title, there are three hashtags: #Constitution #Madhesh #Blockade. Written by Basanta Basnet—a well-known journalist—the book was published by Fine Print in 2018.

The semantics of the cluster of titles speak volumes. The first is that the year 2072 or 2015 carries an albatross around its neck. The cause of the dismay is indicated by the words paraded in the subtitle. One lexicon conspicuously missing in the cluster of words in the title but treated with importance in the book is the devastating earthquake of April 2015. This book is architected principally by analytically putting turns of events in the Tarai region of Nepal. But the politicians who remained intransigent about writing and introducing the first constitution under the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal despite the Madhes movement and demands from different sections of society, the media and books, were swayed by the power of the earthquake more than anything else. I translate a section of the book to show that:

"Maoist Chairman Prachanda was in the Dhapasi residence of his guru Mohan Vaidya 'Kiran'. While they were discussing the post-split scenario in the party and subjects related to the constitution, the earth suddenly started shaking. The leaders ran out in panic into a narrow lane. While rushing out, Prachanda managed to speak in a breath, 'I was not frightened like this even in the war'. Mohan Vaidya, … added, 'Yes indeed, we were all frightened by the earthquake'. Between the aftershocks, Prachanda had said to Chairman KP Oli, 'I had lost all hope of living. Now forgetting all our bitterness we should engage in declaring the constitution. Let us talk and finalise who should sacrifice what. If we die suddenly without declaring the constitution, the people will curse us'." (35). Basnet has cited Sarojraj Adhikari's article published in Kantipur (September 17, 2015) for the above story.

Eloquent narrative

This is a very eloquent narrative. Basanta Basnet links this incident to the 16-point agreement signed on June 8, 2015 by the four major parties—Nepali Congress, CPN-UML, UCPN-Maoist and Madhesi Janadhikar Forum-Democratic—vowing to take the constitution making process ahead. Prachanda is often cited as saying that if they had waited to further refine or dovetail it, the constitution would never have been declared. The post-earthquake 16-point agreement went down in history as a turning point. It shows how the parties tend to choose moments that are triggered by events like this or are propelled by events including geo-political conditionalities to make political decisions. But interestingly, the Maoists were fated to live with the spectrality of history with a greater stake than the other parties. It would be appropriate to recall Jacques Derrida's book The spectre of Marx here based on the opening statement, ‘A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism,’ in The Communist Manifesto (1848).

Evoking the same spectrality, Basanta Basnet says, "The Maoists were going to be condemned to live with the fate of updating the 10-point agreement that they had made in Delhi 10 years earlier." (37). Basnet has brilliantly foregrounded the Maoists' role because, interestingly, the onus of making agreements, abiding by them and also juggling other political parties for that significantly lay on the shoulders of the Maoists. Basanta also refers to the wrath of India for not being consulted during this agreement, which could have precipitated the nakabandi or embargo that lasted for four and a half months. As it is a fairly recent experience, this does not need any explaining.

Basanta Basnet wants to draw the attention of the readers to the fact that the genesis of the Constituent Assembly had started very early on, immediately after the political change of 1950. Drawing a conclusion from history, Basnet says, "The history of the dream of 65 years of writing the constitution from the Constituent Assembly, unlike the claims made in speeches today, did not see tantalisingly homogenous times. Sometimes, the issue lay dormant; and sometimes, it appeared to move at a slow pace. (81). Basanta's conclusion is based on his direct experience of the tumults of the year 2015. What I like most about this book is Basanta Basnet's focus on the Madhes movement. Though I don't have space here, I want to write briefly why I like this book that gives the history of Madhes political initiatives and the struggle for recognition and equality, by juxtaposing that with other very important political movements and events including the big earthquake.

Madhes identity

The book captures the political history of Nepal, not least the relationship between hill-dominated politics with Madhes identity politics. Basanta has given the history of the pioneers of the movement of the Madhes identity consciousness in Nepali politics. The first section of the book mentions, albeit briefly, the ideas of Madhesi politicians like Bedananda Jha, Raghunath 'Madhesi', Ramrajaprasad Singh, Bhadrakali Mishra, Gajendranarayan Singh and others. In this cogently written book, Basanta Basnet has captured the turbulent times in the Tarai, the uprisings, brutalities, bloodshed, ambivalent approaches of the leaders of Madhes to the nakabandi, and formations and dissolutions of relationships between the Madhesi parties and other political parties, all in the year 2015.

Reading this book is like moving with a cyclone, an important year in Nepali history whose intensity is added by the natural calamity. There is no point in reiterating the history that we have just experienced, and the Madhesi people's demands still forming the agenda for amendments to the constitution. This is a fair and non-partisan work of an active and competent journalist whose writing is based on this wisdom that he puts at the beginning of the book: ‘Our political parties are not eager enough to search for the plurality within unity, and transform that into the life force of the nation.’ And Basanta Basnet sees that the grand changes that began from the 2060s and passed through a period of writing the constitution need to be viewed with a sense of vigilance for democratic rights.

5.12°C Kathmandu

5.12°C Kathmandu