Climate & Environment

Trees could save Kathmandu. But can Kathmandu save its trees?

As more trees and open spaces disappear in the name of urbanisation in the Kathmandu Valley, unwelcome—and unhealthy—changes are expected to arise.

Marissa Taylor

Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha remembers growing up in a Kathmandu that looked nothing like it does today. That Kathmandu was all green fields, with just a smattering of mud houses--the remnants of which one can still see on the fringes of the Valley. The roads were dotted with jacarandas and massive peepal trees, whose branches spread out against the blue sky, providing pedestrians with dappled shade.

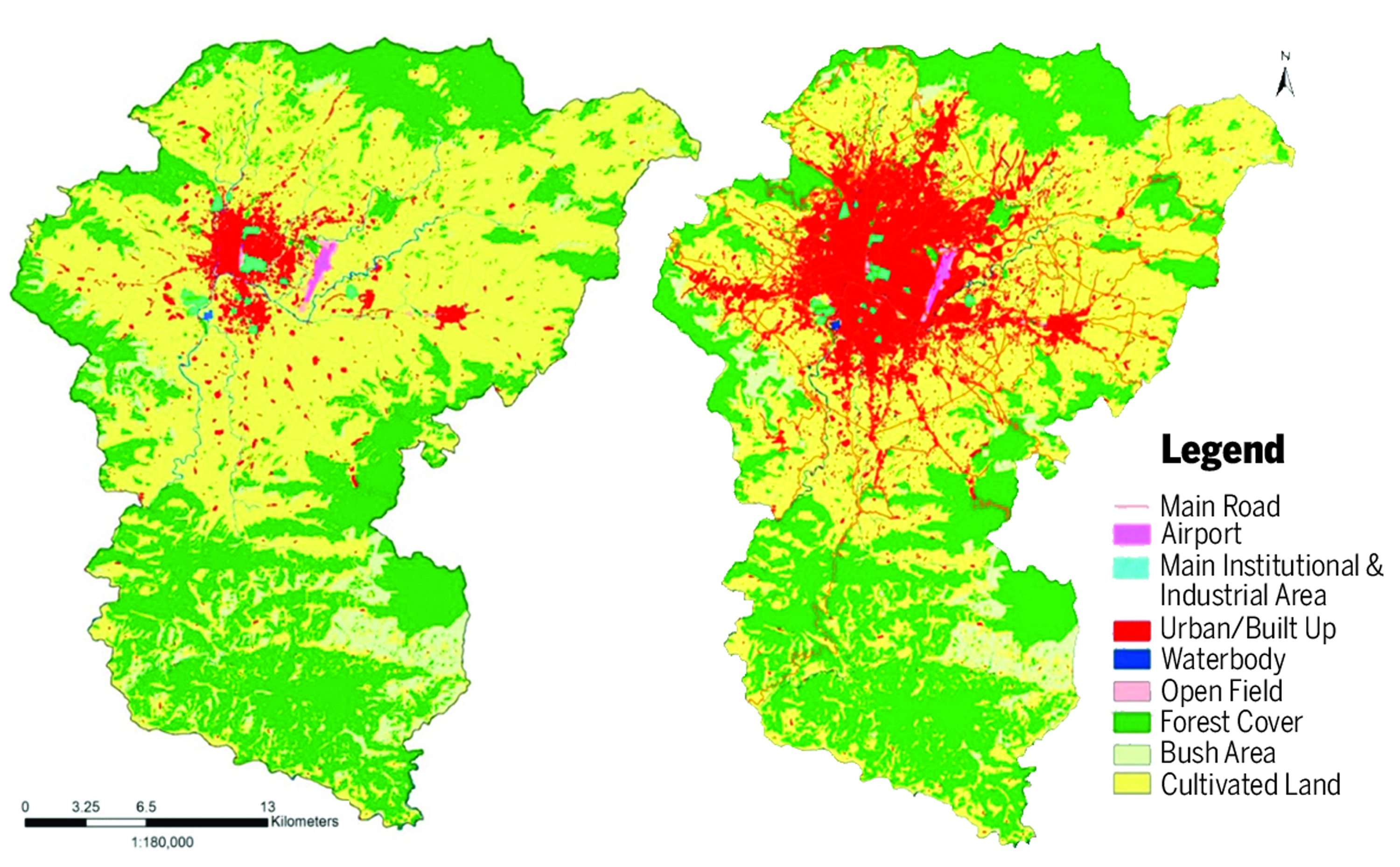

But as Shrestha grew up, Kathmandu expanded. Changes were slow at first, up until the 1960s. But by the 1980s, as Nepal opened up to the world, rapid ribbon development began to escalate. Roads were built everywhere and houses alongside them. People started swarming into the Capital, and before anyone knew it, the face of Kathmandu had changed.

“The Kathmandu I knew has completely vanished today,” says Shrestha, now 84, a conservationist and a retired botany professor at Tribhuvan University.

Today, the rich, arable green fields of Kathmandu are grey, cold concrete. Swathes of forests are now tightly constructed urban spaces, which are eating into the forests on the ridges of Kathmandu. Kathmandu Valley’s green cover consists of a few scant forest patches, like the religious forests of Sleshmantak, Pashupati, and Nilbarahi in Bhaktapur. The only forest that exists inside the Ring Road is Rani Bari in Lazimpat, where conservation work started some 16 years ago.

Kathmandu has one of the fastest rates of urbanisation in South Asia, with an annual urbanisation rate of 3.94 percent. As the city expands, its tentacles spreading out and engulfing the surrounding hamlets, fields and forests, it wouldn’t be inaccurate to assume drastic changes are yet to come. Last week, the Kathmandu Ring Road Improvement Project announced that it will cut down more than 2,000 trees along the 8.2km Kalanki-Balaju-Maharajgunj road section, as a part of a drive to expand the road from three to eight lanes. The announcement sparked public outrage, with environmentalists, activists and urban planners even staging a protest against the decision on Thursday evening.

Conservationists believe haphazard plans like these will be catastrophic for the Valley and its people. As more trees and open spaces disappear in the name of urbanisation, the concrete jungle looms large, robbing the city of the very character that once felt like home to a generation of citizens like Shrestha.

“By giving more importance to economic development, we have neglected nature for decades,” says Shrestha. “And all we got in return is a Kathmandu that now suffocates in an ugly mess of dusty roads and congested houses.”

.jpg)

How did Kathmandu get here?

Kathmandu’s problems, however, began long before rapid urbanisation projects started to take off in the country. According to Shrestha, the genesis can be traced to around 1958, after the nationalisation of forests.

“In an effort to contain timber smuggling to India via the Tarai, the government nationalised all forests. This prevented people from using any forest products and so, they had no incentive to take care of the trees,” he says. “For these people, there was little economic benefit in taking care of trees.”

Soon, road projects started sans any land use policies in place. It was only in 2013 that the Land Use Policy was formulated, after much damage had already been inflicted. The policy was recently revised in March, earlier this year.

“Because there were no policies in place, people started building houses on perfectly arable land to make easy money. Who would prefer farming instead of just earning money by leasing the same land?” says Shrestha. This led to land being scarcer, which means its value skyrocketed. Land slowly became one of the priciest commodities in Kathmandu.

“Because of this rise of land prices and a lack of land planning strategies, there was immense pressure on forests, landscapes as well as green areas in and around the Capital,” says Shrestha.

“With no formal information system in place, the value of land was determined more by social and economic factors than the quality of soil,” says Mahendra Subba, an urban planner and consultant for the Asian Development Bank, who oversees development projects in the city. “This gave way to a lot of haphazard urbanisation, felling of trees, and conversion of agricultural land into urban mess.”

Government data, however, does not sync with what’s happening on the ground. Officials from the Kathmandu Valley Development Authority and data from the District Forest Office in Kathmandu suggest that forest cover has inexplicably been increasing in the Valley. Records show that forests made up only 30.4 percent of the total land area in the Valley back in 1984. That number increased to 36.94 percent in 2015.

“You don’t need data to tell you that trees in Kathmandu are fast disappearing. All you have to do is look around,” says Subba.

But what explains the data? According to Subba, the definition of forests differs from institution to institution, with some considering even four to six trees and shrubs as a small forest unit.

[Read: Kathmandu Valley’s stone spouts were once gushing with water. Now they’re slowly disappearing.]

“The trees in the Valley are in no way adequate to maintain public and environmental health,” says Subba. According to the Kathmandu District Forest Office, while the number of trees inside the city proper might have decreased, forest cover on the fringes of the Valley has grown, leading to its net rise. But this discounts the fact that the city itself has been denuded.

While talking numbers, it is also important to note the conversion rate of agricultural land into urban areas in the Valley, which has been consistently high over the decades. In 1984, agricultural land made up 64 percent of the Valley. By 2015, it had been reduced to 41.4 percent. The trend of converting agricultural land into urban spaces had taken hold, and as such, there was little land available for trees to grow.

But trees play an extraordinarily important role in our cityscapes, which according to environmentalists, the public has taken for granted.

“What we are doing to the forests, to the environment around us, infact, is a reflection of what we are doing to ourselves,” says Bharat Sharma, professor of environment and landscape at Tribhuvan University, who was the deputy director general of Building and Urban Development for 35 years before retiring recently.

“Urban planning is more than just planting trees,” said Sharma, who completed his PhD on Kathmandu’s shrinking open spaces. “It is about bringing together a forest’s ecology into urban planning with a proper integrated management plan.”

The case for more trees

Studies show that a mature tree can absorb up to 150 kg of carbon dioxide per year, which means they are excellent filters for urban pollutants and fine particulates. Conservation advocates say the drive to plant more carbon sinking trees can help mitigate the effects of climate change, but perhaps it can also provide an answer to Kathmandu’s degrading air quality.

“Trees are like the lungs of any place. By chopping them down, we are intentionally choking the city we live in,” says Sharma.

Strategic placement of trees in cities can help to cool the air too, between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius, thus reducing the urban “heat island” effect, which is a common phenomenon in urban areas that lack naturally occurring vegetation. Tall buildings, concrete and asphalt trap heat and thus warm core city areas, creating a “heat island” effect. This can be seen prominently in the Valley because of its bowl-like shape, which traps heat and air.

[Read: Tree guards and fresh saplings rekindle hope for Kalanki-Koteshwor road greenery project]

Besides environmental benefits, trees--and the open spaces that they are part of--also have recreational and aesthetic value. In Nepal, open spaces have a lot of socio-cultural importance. “Traditionally, cities were designed to have enough open space for cultural functions. These spaces give colour to our otherwise cold structures,” says Sharma.

Research also shows that living in close proximity to green spaces can improve physical and mental wellbeing, for example by decreasing high blood pressure and stress.

Beyond helping reduce carbon emissions, trees play another vital role: absorbing and retaining water. During rainfall, much of the water is absorbed by tree roots. On average, a mature tree can absorb up to 1,000 gallons of rainfall every year. And without trees, the absorbing capacity of any place will diminish, which is exactly what’s happening in Kathmandu, especially during the monsoons.

“In places where there are no trees, there is rapid rainfall, and the water runs into rivers, increasing flooding. This is evident in many places in the city, like Jamal, every year. This year, floods wreaked havoc in the Kuleshwor area as well,” says Rajendra KC, deputy director general of the Department of Forest and Soil Conservation. “If there were more trees to absorb that water, the problem could be easily averted.”

Fewer trees and more concrete roads also mean that Kathmandu Valley’s water table levels will decrease dangerously, with aquifers drying up. The daily demand for water in the Valley is currently 400 million litres. Already almost all households depend on groundwater for their daily use, even Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited, which delivers water to the Valley’s denizens, bores 120 million litres of water every day. But groundwater can become a non-renewable resource if it is over-extracted since it takes years to recharge. And trees play a vital role in the process of recharging aquifers that lie deep beneath the earth’s surface. A lack of trees could bring on impending disaster for the people of Kathmandu, where many are already resorting to using water tankers.

“The effects are already being seen. Kathmandu has no water,” says Shrestha. “This will invite all sorts of conflict in the future.” Shrestha says the water in his home in Sanepa comes from Godawari because the core city does not have aquifers. In about 15 years when Godawari’s water levels recede, then the water to Shrestha’s house will stop flowing, because the people of Godawari will not want to share water when there’s a dearth of it.

“If we use up our resources without giving them a chance to replenish,” says Shrestha, “then one day we will run out.”

Planning cities around trees

As if things were not already grim, the Ministry of Urban Development has proposed a plan to build an ‘Outer Ring Road’, and in the process, cut through the few remaining forests and fields that currently surround the city, like Nagarjun, Tokha, Chunikhel, Gokarna, Jagati, and Bungamati. This plan is certain to have a ripple effect on the Valley’s ecosystems.

The ministry also plans to build four ‘smart cities’, under Kathmandu Valley Development Authority (KDVA)--the body tasked with carrying out urbanisation works in the Valley, which according to reports, will cover a total area of 130,000 ropanis, with the biggest smart city, in the north-east of the Valley, covering 100,000 ropanis of land. This city is estimated to spread through Nagarkot, Jorpati, Shankhu, Bhaktapur, Nepal Army Training Academy and will be linked to the Araniko Highway. The other three cities will be spread over 10,000 ropanis each.

To offset the damage that has already incurred, and to make the Valley livable again, paying close attention to trees and reviving them is crucial, environmental experts say, especially on the level of policymaking.

“Policies and development work should be public centric and completely transparent,” says Saurabh Dhakal, a social campaigner. “Development projects can be carried out around trees; they don’t need to be chopped down. Instead of being a role model for other cities in the country, Kathmandu is the perfect example of what not to do when you’re developing a city.”

To see how it’s done, you don’t have to look very far. Sustainable development works have been carried out by several countries in the region, like Bhutan, Vietnam and Singapore. Among them, Singapore’s quick progress has impressed the world. After industrialisation brought heavy pollution, the country created the Singapore Green Plan in 1992 to tackle its problems. Today, it is one of the greenest urban cities in the world, with plans to cut carbon emissions intensity by 36 percent by 2030, and one way it plans to do so is by adorning its high-rise buildings with greenery--something Kathmandu could imitate.

Closer to home, Bhutan’s policies are worth replicating as well. It is the only country in the world that is carbon negative, which means it produces more oxygen than it consumes, a feat it has been able to achieve by ensuring that at least 60 percent of the country is covered in forests. The country’s focus on pursuing a 'green' economy, a drive that was launched in 2010, has prompted the nation to make decisions that are not the best for development but ensure environment protection, such as restricting tourist numbers and opting out of mega projects like the Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal regional road connectivity project.

As for efforts by the Nepal government--under KDVA again--it has drafted the Strategic Development Master Plan (2015-2035), which officials say “focuses on promoting urban forestry”, but the draft itself is very vague, with broadly outlined plans.

The construction of the four ‘smart’ cities is also part of this master plan. But conservationists believe the plan is flawed, and is based on--among other things--population projection and vehicle ownership, ignoring many important aspects, such as the Valley’s large transient population.

.jpg)

The government has also taken up a momentous task of planting 40 million trees this fiscal year, dubbing the nationwide campaign as the ‘Year of Plantation’. In June, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli inaugurated the planting of 2,600 saplings in the country to much fanfare. However, reports of the saplings dying had already surfaced just a few days after the event.

Initiatives such as these come by every year. Only in 2017, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City had announced that it would plant trees on traffic islands, along the road and open spaces in congested areas like Sundhara, Jamal, Ratna Park and New Road. The same year, it also launched a campaign to plant 30,000 trees in the Valley. None of the plans came to fruition. Back in 2013, KMC announced its two-tree policy, according to which, blueprints of new houses in Kathmandu would not be passed by the authorities if houses did not accommodate the planting of two trees. It was expected to ensure the planting of 100,000 trees.

These are just some of the instances of how the government makes vague ambitious plans and abandons them halfway. To facilitate planned development through an adequate supply of serviced plots for housing, a land pooling scheme was initiated in 1988 in the Kathmandu Valley. As per the scheme, the government acquired privately owned land, divided it up, planned and built necessary infrastructure, replotted land parcels and returned the land to the owners, with a 12 to 30 percent reduction but with the availability of facilities. But with land prices constantly rising, the scheme did little to reduce damage, says Sharma.

But there is some good news: Kathmandu is blessed with sub-tropical temperatures and fertile soil, and so can accommodate a range of trees from dhupi, salla, devdar, jacaranda, and bougainvillea.

But ecologists say planting more trees is just the first step of the process. “You have to nurture, prune, and water the saplings as well,” says Shrestha.

“Another good example that shows how concerned our government is regarding the environment and public health can be seen with how they have built the eight-lane ring road from Koteshwor to Kalanki,” says KC. “The design of a road is not limited to asphalting it. The road was built over trees.”

And despite all the inadequate plans and signs that point to a bleak future, the government is optimistic.

“Things are going to be different in six-seven years, you will see,” says Hari Bahadur Shrestha, chief of the environment division at Kathmandu Metropolitan City, adding that KMC--in close coordination with KDVA--is committed to making Kathmandu ‘green’ again, and has already planted around 1,500 trees along the Koteshwor-Kalanki road.

But as bulldozers get ready to axe the 2,000 or so trees along the Kalanki-Balaju-Maharajgunj road section next week, and the draft of the detailed project report of the biggest ‘smart’ city draws completion, conservationists say now is the time for the government to rethink its approach to development.

“It’s not that development has to stop, but a sustainable approach that keeps in mind the environment must be taken,” says Shrestha. “We have exceeded Kathmandu’s carrying capacity, and unless we buckle up right now, disaster looms.”

ALSO, READ:

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published.

Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

8.99°C Kathmandu

8.99°C Kathmandu