Climate & Environment

This is why leopards are entering our cities

Rapid urbanisation and a lack of prey are pushing leopards towards the cities—and humans.

Marissa Taylor

On the morning of June 1, 2016, Meena Pokharel woke up to disturbing news. At 7 am, her maid told her that there was a leopard in the garden. Not believing her, Pokharel rushed downstairs and to her surprise, there really was one—staring back at her with inscrutable yellow-green eyes.

Unsure of what to do, Pokharel called the police and they in turn called the Central Zoo and officials from the Division Forest. The news spread and by 10am, Pokharel’s Kuleshwor home was surrounded by more than a hundred people. A leopard was on the loose, and everyone wanted to catch a glimpse of the elusive animal.

At around 1pm, the rescue team from the zoo finally tranquilised the leopard and then took it to the Central Zoo, after which it was relocated to Parsa Wildlife Reserve.

Kuleshwor is one of Kathmandu’s more densely populated areas, located to the south west of the city, near the Ring Road. With the nearest forest just about five kilometres away, Kuleshwor is adjacent to bio-corridors—which animals use to cross between habitats—along the Balkhu, Bagmati and Bishnumati rivers.

Pokharel’s home is the first in a residential area—just around 20 metres away from the main road—with a few bushes and trees, adequate for an adult leopard to hide in.

Reports of such leopard excursions have become more frequent over the years, with over two dozen ‘strayings’ reported in the past five years, according to Central Zoo statistics. The same year that Pokharel found a leopard in her garden, another was found inside a home in Baneshwor. Only last month, on May 9, officials from the Central Zoo were notified about a leopard sighting on a tree branch in Tokha. As urban Kathmandu continues to expand, it encroaches more and more on the surrounding forests—the habitat of the leopard. This is the primary reason behind such recurring leopard excursions, say wildlife conservationists and national park officials.

But the number of leopard strayings does not reflect the real costs that urban expansion is inflicting on these cats. An estimated 66 percent of their range in Africa and 85 percent in Eurasia—the two regions of the world where leopard populations thrive—have been destroyed over the past five decades. In many areas around the world, the only alternative left for these big cats is to attempt to survive alongside humans.

In Kathmandu, the effects of urbanisation on leopards have yet to be studied but educated estimates can be made, particularly in terms of changes to their habitats, behaviour and feeding habits. As an apex predator, the leopard is a vital ecology quality control marker that keeps our ecosystem in check; however, currently, the status of its existence is in question, and there are few studies that show where the leopard population really stands.

“Despite inhabiting a huge area, from across the country’s Tarai to the mid-hills at around 800 metres to 3,000 metres above sea level, the leopard is one of the least studied animals in the country,” says Laba Guragain, national park ranger at the Shivapuri-Nagarjun National Park. And that in itself should be a cause for concern.

Entering human settlements

The leopard (Panthera pardus) is one of the most widely distributed felids across the forested landscapes of the Indian subcontinent. It is one of four big cats found in Nepal--besides the tiger, snow leopard, and clouded leopard. This spotted cat, with its short powerful limbs, heavy torso, and large black spots grouped into rosettes, is a solitary creature that is almost nocturnal.

And unlike most other big cats, they are very adaptive by nature, says Guragain. They can prey, for example, on anything from mice and porcupines to monkeys and dogs. They can thrive in deep forests and near human settlements. That adaptability, combined with a genius for hiding in plain sight, means leopards are capable of living alongside humans.

“But when leopards are found outside of forests in areas with high human density, we think they have strayed. We forget that it’s their home too, just as much as ours,” says Guragain.

“By nature, predators, particularly males, travel long distances in search for two things: food and mates,” says Guragain. To travel from one forest to another, leopards use natural corridors that mostly follow rivers and through fields.

“Before Kathmandu’s population grew, when there were fewer houses, there were small forest patches scattered everywhere, like stepping stones, giving leopards enough area to avoid human contact and reach their destinations,” says Guragain.

Even today, despite much of Kathmandu’s forest and agricultural land being turned into buildings, a few such pockets of forests remain, says Guragain, like the Shivapuri-Gokarna-Pashupati Bankali-Sallaghari route.

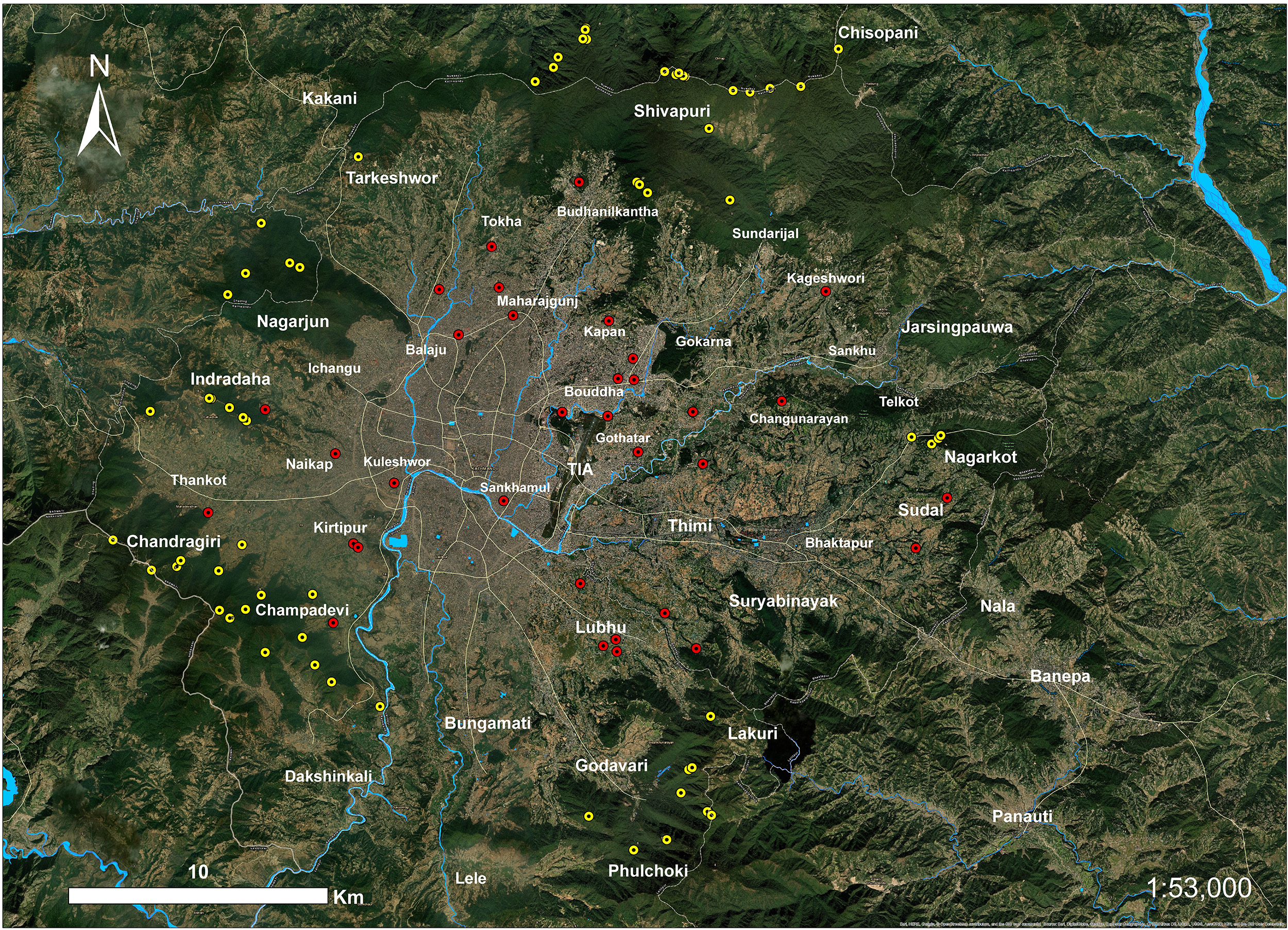

By using such trails, biologists believe, leopards from Shivapuri travel to community forests beyond Bhaktapur in search of mates to avoid genetic inbreeding, and to ensure genetic exchange. Another corridor still accessible to leopards is the Dakshinkali-Champadevi-Chobar-Kirtipur route, which follows the Bagmati River.

But Kathmandu continues to grow exponentially, both in terms of population and housing. Kathmandu's 2019 population is estimated to be 2.5 million, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics Nepal, a number that was only 104,479 in 1950, according to the UN World Urbanization Prospects. The city proper has a population density of 20,288 people per square kilometre (52,550 residents per square mile). And given that the leopard’s home range is at least 25-30 square kilometres, interactions with humans are inevitable.

“Leopards try to avoid human contact as much as possible, but in that process itself, they end up in city areas,” says Narayan Koju, assistant professor of natural resources management at Pokhara University. “For example, leopards take bio-corridors to go from one place to another, but because these corridors have been broken up by human settlements, leopard-human interactions become a big possibility.”

To study the leopard’s distribution dynamics in the Kathmandu Valley, Prajwol Manandhar, a wildlife conservationist and data scientist at the Center for Molecular Dynamics-Nepal, collected scat specimens from six major hills surrounding the Valley—Chandragiri, Shivapuri, Nagarjun, Phulchowki, Indradaha, and Nagarkot. Through his research, the Kathmandu Leopard Project (KLP), one of the first projects to study the leopards around Kathmandu, Manandhar has been able to identify the DNA fingerprint of individual leopards, their sex, movement patterns, genetic closeness, and the country’s first molecular assessment of their diet.

While Manandhar’s team is currently investigating the movement patterns of individual leopards through a DNA fingerprinting technique, the spatial data demonstrates how leopards are indeed using human spaces to move from one intact forest patch to another, such as from Chandragiri to Indradaha to Nagarjun. While doing so, leopards are having to move through the dense settlements of the Chandragiri and Nagarjun municipalities, crossing places like Thankot, Matatirtha, Kirtipur, Dahachok, Balambu, Syuchatar, Naikap, Ramkot, Bhimdhunga, and Ichangu. They also have to cross through the busy Tribhuvan Highway, the primary western entry and exit point of the Kathmandu Valley. All of these places have seen numerous human-leopard conflicts in the past.

Besides their search for a mate, experts believe that leopards now have to travel further in search of food—as a result of urbanisation degrading and fragmenting their habitats. “Even in a healthy habitat, it’s not easy for a leopard to capture its prey; it might take the leopard multiple attempts to capture its prey,” says Guragain.

“Let’s take Chandragiri as an example. A few years ago, it was a deep forest but to make way for the cable car, forests were cut. That has fragmented the habitat, affecting the entire ecosystem,” says Yadav Ghimire, conservation biologist at Friends of Nature. With the increase in human activity in the area, animals such as barking deer—which is also solitary in nature, and a leopard’s main prey—will try to find a new, quieter home, he says. This means a decline in prey numbers, which forces leopards to enter cities to find alternative food sources.

“In a fragmented habitat, where sources of water have been disrupted by roads and soil erosion, it becomes tougher for predators to find prey. But with easy prey available in the fringes of the forests, they often come into the buffer zones and stray into human settlements to hunt for easy food,” says Ghimire.

Change in feeding behaviours

This easy accessibility of food has possibly even influenced their food habits, suggests Manandhar’s research, which has inputs from wildlife geneticists Jyoti Joshi and Hemanta Chaudhary, who ran the region’s first leopard molecular diet analysis. This technology allows the assessment of the entire biodiversity landscape through a singular leopard scat, indicating not only what these predators feed upon, but also what their prey base looks like.

According to their limited preliminary data, Kathmandu’s leopards are feeding on the traditionally expected wild boars, monkeys and porcupine, but they have also been feeding largely on local poultry and cattle. The study also found one case of a female leopard feeding on a dog, in Matatirtha last September. A half-eaten Japanese Spitz was found less than a few hundred metres away from the Chandragiri forest. Manandhar’s team sampled the neck region of the dog’s carcass to confirm if it was a leopard kill.

Despite being early days, the feeding behaviour clearly displays the highly adaptive nature of leopards and could indicate that if they are near human settlements, they will choose to feed on the easily accessible cattle and poultry.

“Our preliminary findings also suggest that intact forest patches that serve as their natural home only provide leopards with enough cover to remain hidden but not enough prey to feed themselves,” says Manandhar. “Hence, they are moving frequently. Further research on monitoring both leopards and their wild prey density is urgently needed. Otherwise, these big cats could perish before we even learn their status.”

From bad to worse

Things could get worse from here—not just for the leopards, but also for the Valley’s ecosystem and biodiversity, say researchers. A 2017 study shows that Kathmandu’s urban area has expanded up to 412 percent in the last three decades, and most of this expansion has occurred with the conversion of 31 percent of arable land. According to a 2014 UN DESA report, for the period 2014-2050, Nepal is expected to remain amongst the top 10 fastest urbanising countries in the world, with a projected annual urbanisation rate of 1.9 percent.

With things as grim as they are for biodiversity, in the name of urbanisation, the Ministry of Urban Development has also proposed a plan to build an ‘Outer Ring Road’ which will cut through the few remaining forests and fields that currently surround the city, like Nagarjun, Tokha, Chunikhel, Gokarna, Jagati, and Bungamati. The Outer Ring Road is certain to have a ripple effect on the Valley’s many ecosystems.

The ministry also plans to build four ‘smart cities’, which according to reports, will cover a total area of 130,000 ropanis, with the biggest smart city, in the north-east of the Valley, covering 100,000 ropanis of land alone. This city is estimated to spread through Nagarkot, Telkot road, Jorpati, Shankhu, Bhaktapur Purano Bato, the Nepal Army Training Academy and be linked to Araniko Highway. The other three cities will be spread over 10,000 ropanis each in three other corners.

“The government’s plans never take into consideration the implications they will have on the Valley’s ecosystem, which has already reached its tipping point. If this [satellite city] plan is brought into effect, wildlife will diminish significantly, or even become extinct,” says Koju.

The government’s recent plan to start safaris inside Shivapuri-Nagarjun National Park and to start cable car services will also add stress to an already delicate system. “The forests of Shivapuri are one of the major sources of water for the entire Valley, disrupting anything in that system will spell disaster,” he says.

Conservation efforts needed

According to IUCN, the leopard was under the ‘least concerned’ category only 12 years ago, in 2007. But now, in its updated National Red List of Threatened Species, the leopard falls in the ‘vulnerable’ category with fewer than 1,000 leopards in the country. But exact numbers are difficult to come by.

“How many leopards are there in Kathmandu is just a ‘guess-timation’, which can be accumulated through different researchers’ findings and assumptions,” says Ghimire. “I would say there are 20-25 leopards in the forests around the Valley, but because a scientific study has never been done, it’s all assumption.”

The leopard also does not fall under the 27 protected species enlisted as per the National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act 1973, and has been given no attention in terms of protection and conservation action plans, awareness programmes and monetary support.

“Just as the tiger population is crucial for Chure conservation, leopards too play an important role in maintaining the ecosystem of the midhills, which constitute more than 60 percent of the total land of Nepal,” says Guragain.

It is vital that apex predators’ populations remain stable for the health of the entire ecological pyramid. The removal of apex predators can have serious consequences for the fragile balance of ecosystems, as the experience of Yellowstone National Park in the US shows, says Ghimire. When the wolf was wiped out in Yellowstone in the 30s, the elk population thrived—pushing the limits of Yellowstone's carrying capacity. These elks then fed heavily on willow, something beavers need for survival—driving beaver numbers to an all-time low. But since the wolves were reintroduced in 1950, the beaver population has stabilised, the willow stands became more robust, and the elk population balanced itself out.

Averting such a situation requires preparation and a knowledge of the ground reality, says Ghimire. But so far, a systematic study to understand the situation of leopards has never been conducted, except for individual research on Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park.

“Carrying out wildlife research takes a lot of manpower, capital and time. Just to radio collar one leopard costs at least 3,000-4,000 dollars,” says Ghimire. For an organisation such as Friends of Nature, coming by that kind of money is tough, particularly with global attention focused on saving tigers and rhinos in Nepal.

More conflicts to come

Conflicts with wildlife are universal, but it is a bigger problem for underdeveloped countries that do not have the means to contain them.

“In the Kathmandu Valley, human-leopard conflict is mostly seen only in the fringe areas, with leopards attacking livestock,” says Bishnu Shrestha, information officer at the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation. “That is because local dependency on forest resources is high. However, despite there being only a small area for concern, there is also a lack of proper management to ensure such conflicts do not arise.”

According to the department, in this fiscal year alone, there have been 24 wildlife attacks that affected human beings, seven of them by leopards—in areas like Syangja, Kavre, Tanahun, Kaski and Arghakhanchi. Despite the widespread fear of leopards, wildlife experts say that these big cats rarely attack humans.

The nature of human-wildlife conflict differs from area to area, says Guragain. “People who live along the fringes of the forests are actually not as afraid of leopards because they see them often, but if a city person sees a leopard then an immediate fear is spread,” says Guragain.

“An animal will never initiate conflict, unless it senses a threat,” says Radha Krishna Gharti, who leads wildlife rescue operations at the Central Zoo and has rescued more than 50 leopards in his three-decade of service. “It’s not just leopards, even a deer or a monkey will attack you if it feels threatened. For example, if an animal feels you might snatch their food or if it feels like you are going to attack them, they will be defensive. A mother can be particularly dangerous if it thinks you are a threat to her cubs.”

But the sight of a leopard alone can cause city folks to take rash actions. “The fear is so great that people are quick to resort to killing leopards,” says Gharti. In the years he has rescued leopards—one time from under a dining table in Kirtipur, another time from a toilet in Maharajgunj—Gharti has seen how unmerciful humans can be when it comes to retaliating, like the time he saw the body of a leopard, beaten to death in Machegaun in 2016. “They had even cracked open its skull,” he says.

“Leopards have been paying the price for much of what humans have done,” says Gharti, talking about the leopard that was electrocuted after getting caught in a transformer in Kageshwori, only a few weeks ago. “If it had been a human instead of a leopard, the issue would have received a lot of attention.”

"The leopard's secretive nature and great adaptability have led to the misconception that this species might not be severely threatened across its range," says Ghimire of Friends of Nature. “But the reality shows that things are otherwise, and without conducting thorough research, we can never be sure. We’re all just working in the dark.

27.48°C Kathmandu

27.48°C Kathmandu